Competing CPTPP bids, Canberra’s contentious China policy choices, and TikTok turbulence

Weeks of 27 February to 19 March 2023

Mea culpa for the delay getting this edition out. I’ve been waylaid by AUKUS and related developments. BCB will get back to its normal fortnightly programming with the next edition.

Australia’s tough trade pact decision

From former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s Report on the Work of the Government delivered on 5 March:

“We should take active steps to see China join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)”.

Quick take:

This is a conspicuous elevation of CPTPP accession as a policy priority for Beijing. It’s especially noteworthy considering that the CPTPP wasn’t mentioned in the 2022 Work Report that followed China’s formal application for membership. Although the CPTPP was mentioned in the 2021 Work Report, the reference was more cautious: “China will actively consider joining the [CPTPP].” (For reference, the CPTPP wasn’t mentioned [so far as I can see] in any other Work Report since that trade agreement was signed and came into force in 2018.) This latest high-level signal suggests the Chinese government will ramp up its efforts to gain CPTPP entry in 2023. This probably also means that Canberra will come under increasing pressure from Beijing to back its bid.

China’s push for Australian support might be especially forceful given the growing signs of a resumption of normal diplomatic exchange and an incremental dismantling of Beijing’s trade restrictions. In the last couple of years, Australian support for China’s CPTPP accession looked wildly implausible. How could Canberra have seriously considered supporting Beijing’s bid in the midst of a total diplomatic freeze at the ministerial level and above combined with extensive politically motivated trade restrictions? As the then Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment Dan Tehan made plain back in November 2021, China’s CPTPP accession would be a nonstarter until Australian ministers could at least talk to their Chinese counterparts. And the point regarding economic coercion was elegantly made (albeit without mentioning China by name) in the joint statement from the Japan-Australia Ministerial Economic Dialogue in October 2022: “Ministers … committed to the continued expansion of the CPTPP to those new economies … with a demonstrated pattern of complying with trade commitments. Ministers noted that economic coercion and unjustified restrictive trade practices are contrary to the objectives and high standards of the Agreement.”

But bilateral diplomatic and trade repair might now dilute the most obvious reasons for Canberra to immediately rebuff Beijing’s requests for support with CPTPP membership. China might therefore decide that now is the right time to relitigate its CPTPP accession with Australia and other countries. Although there’s no concrete evidence that I’ve seen in the open source material, one can easily imagine Chinese ministers and diplomats privately renewing their push for Australian support. With the bilateral relationship stabilising and heading “back on the right track,” the Chinese government might argue that Australia no longer has any obvious grounds for not supporting China’s plans for CPTPP membership.

Regardless of whether one thinks Canberra should swing behind Beijing’s CPTPP push (I won’t try to parse and adjudicate all the complex economic and strategic calculations in this edition), China’s CPTPP goal poses yet another tough policy choice for the Australian government. Bringing China into the CPTPP would, ceteris paribus, produce economic gains for Australia and other countries. Australian support for China’s membership would also be welcomed by Beijing and so would probably assist the Albanese government with its goal of further stabilising the Australia-China relationship. CPTPP membership might (though it’s a very questionable might) also encourage China towards better standards of trade behaviour by enmeshing it in more trade rules.

But such support would also be deeply politically unpalatable in many quarters given China’s more-than-two-year-long economic and diplomatic punishment campaign against Australia. Moreover, China’s trade measures against Australia in recent years provide a prima facie reason for approaching with caution initiatives that would foster deeper trade connectivity with China. This case for caution is likely to be especially strong considering the (very patchy) record that trade agreements have at restraining China from economically coercing other countries, including Australia.

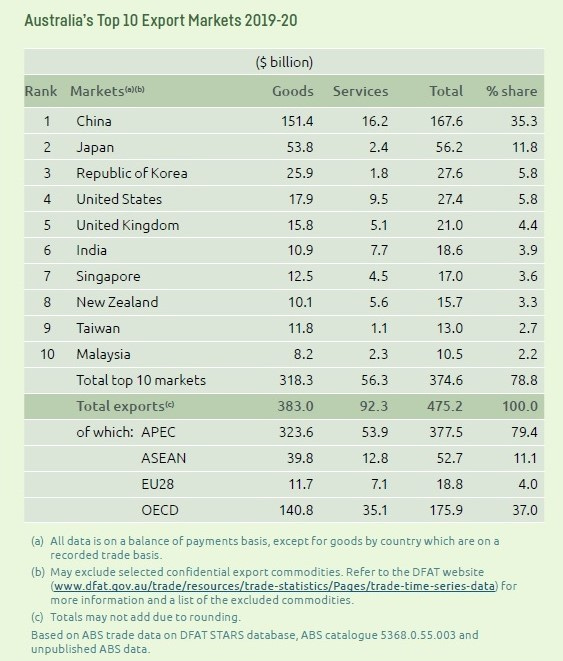

Then there’s the Taiwan factor. Just as Beijing might be planning to pile more pressure on Canberra to support its CPTPP bid, Taipei has an as-yet-unrealised trade agenda with Australia. Taiwan seeks CPTPP accession and is on the record looking for Australia’s support. Taiwan’s role as a reliable economic partner for Australia in recent years stands in stark contrast to China’s extensive use of economic coercion. (Not only has Taipei not pursued those kinds of adversarial trade policies against Canberra, but like Australia, Taiwan has actually been the victim of China’s economic coercion.) Taiwan is also (depending on the year of trade data one uses) the only one of the top ten Australian export markets with which Canberra doesn’t have a bilateral free trade agreement (FTA). With plans for an Australia-Taiwan FTA dropped in 2016-17 due to pressure from China, bringing Taiwan into the CPTPP would (to some extent) make up for Australia’s lack of bilateral FTA with one of its largest export destinations. (I’d add to this list of reasons for supporting Taipei’s CPTPP bid the broader strategic goal of engaging with Taiwan in the trade arena to keep international space for open for one of the region’s leading liberal democracies, but that’s an argument for another edition.)

Yet for all the reasons for Australia to support Taiwan’s CPTPP accession, China is likely to strongly oppose such a decision. And Beijing might be especially aggrieved if Canberra jumps on board with Taipei’s CPTPP plans while at the same time rebuffing China’s request for support. Given Beijing’s efforts to undermine a wide range of forms of political, diplomatic, economic, and institutional engagement with Taipei, China is likely to also view support for Taiwan’s CPTPP bid as a challenge to its goal of internationally isolating the Taiwanese government. The Australian government might therefore be loathe to support Taiwan’s CPTPP accession for fear of upsetting China. This might be especially so considering the way in which Prime Minister Anthony Albanese himself and some of his ministers have trumpeted relationship repair with China as one of their signature foreign policy achievements in office.

Of course, the ongoing process of getting the United Kingdom into the CPTPP might make Australia’s position on China’s and Taiwan’s competing membership bids moot for now. But eventually the UK accession will (presumably) conclude, and both Beijing and Taipei will likely come knocking on Canberra’s door with renewed vim and vigour. At that point, Australia is likely to face a tough policy choice that pits a complex set of powerful economic and strategic considerations against each other.

A revised list of Canberra’s contentious China policy choices

Prime Minister Albanese responding on 16 March to a question about the Darwin Port review:

“We’ll announce it when it’s announced. Rather than putting a timeframe on it. I’ve got the relevant agencies have been [sic] asked to examine that. They’ll come back to me and then I will release it and make it in a transparent way.”

Quick take:

In previous editions, I’ve written about tough China policy choices for Canberra as it seeks to stabilise ties with Beijing and prosecute Australian interests. The four key decision points that I’ve previously nominated are:

The use of Foreign Relations Act powers to veto Confucius Institutes at Australian universities;

The imposition of targeted sanctions on Chinese officials and entities implicated in severe human rights abuses in Xinjiang;

The review of the 99-year lease of Darwin Port to the Chinese company Landbridge Group; and

Periodic decisions on foreign investments from China.

The last few months have pushed at least a couple of these tough choices out of the Albanese government’s in-tray. On the Confucius Institutes decision, Canberra appears to have so-far successfully threaded the needle of putting these institutions on notice without aggravating Beijing with a veto. Meanwhile, despite the Albanese government’s prolific use of targeted sanctions against Russia, Iran, and Myanmar (e.g., here, here, here, and here), Canberra has opted (at least for now) for the cautious and morally ambiguous approach of not imposing targeted sanctions against Chinese officials and entities implicated in severe human rights abuses.

Regardless of the rights and wrongs of these decisions (as regular readers will know, I have misgivings about the sanctions decision in particular), Canberra has for now largely neutralised these first two issues as live dilemmas. To be sure, the Albanese government will periodically be criticised for not sanctioning Chinese officials and entities and for taking what some will see as too soft a touch on Confucius Institutes. But in both cases, Canberra has (politically at least, if not morally and in security terms) resolved the dilemma by taking a policy path that neither angers Beijing nor prompts widespread and strong domestic opposition. That’s not to say that these issues won’t once again become live issues for the Albanese government, much less that they shouldn’t still be points of public debate. But for now, at least, they don’t pose tough decision points for the Australian government.

But just as some hard China policy choices might have been (largely) neutralised, others remain and still others are being added to the in-tray. The review of the Darwin Port lease is ongoing, and, as I’ve previously written, still poses a dilemma for the Albanese government. Meanwhile, despite the fortuitous timing last month of the Baowu Steel approval that overshadowed the Yuxiao Fund rejection, Canberra will face the ongoing dilemma of how to combine bilateral relationship repair with the periodic rejection of Chinese investments. With China still concerned about what it perceives to be the unfair Australian environment for its businesses, investment reviews will remain a sensitive area of bilateral ties.

On top of these enduring tough China policy choices, I’d add one likely and two possible decision points that could challenge Canberra in the months ahead. Per the above, Beijing’s and Taipei’s competing CPTPP bids are likely to pose a tough China policy choice for Australia. Projecting froward, I’d also expect difficult decisions for Canberra stemming from the deepening China-Russia relationship and the handling of TikTok and other Chinese-owned apps in the broader Australian market. These decisions are not here and now like the Darwin Port review and foreign investment determinations, and they are more uncertain than the likely choice over Beijing’s and Taipei’s competing CPTPP bids. But the overarching trendlines of deepening security concerns surrounding Chinese consumer-facing apps and Beijing’s tighter strategic embrace of Moscow mean there’s a growing chance that Canberra will need to grapple with yet more tough China policy decisions.

Although Canberra is expected to soon ban TikTok on federal government devices (on which, more below), the direction of travel on the app in the United States may further spur a debate in Australia about much broader restrictions on market access for TikTok (and potentially other Chinese-owned apps). Calls (e.g., here and here) have already emerged for broader market restrictions on TikTok, while influential parliamentarians remain deeply sceptical of the app. The issue of mitigating the potential national security risks of Chinese-owned apps like TikTok while also not unduly restricting the rights of individuals and diaspora communities is politically and morally fraught. This is especially so in the case of WeChat, which provides communication and a range of other services for millions of Australians. I don’t presume to have answers on the right balance between mitigating security risks and safeguarding individual freedoms. But without getting into those kinds of normative questions of what the Australian government should do, it seems at the very least that there’s a growing chance Canberra will have to grapple with a complex set of questions about the kinds of broader security and/or market restrictions that should be placed on Chinese-owned apps like TikTok.

Meanwhile, depending on how much support China is willing to offer Russia during its war of aggression in Ukraine, Australia might also have to decide whether to extend its sanctions of Russia’s supporters to Chinese individuals and entities. As the state visit to Russia by China’s leader Xi Jinping underlines, Beijing seemingly has no compunctions about deepening its economic engagement and diplomatic support for Moscow as it wages a brutal war against Ukraine and its people. Meanwhile, evidence has emerged suggesting that Chinese entities are exporting equipment and weapons that could aid the Russian war effort, while US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said in February that information suggests China is “considering providing lethal support” to Russia. It remains to be seen whether China’s support for Russia will evolve into the kind of technological and military assistance that prompts the United States to impose fresh sanctions against China. But if Beijing’s assistance crosses that threshold (of course, not necessarily guaranteed), Canberra is likely to be very quickly confronted with the question of whether to sanction Chinese individuals and entities. In such a scenario, Australia would likely find it extremely hard (both morally and diplomatically) to not throw down the sanctions hammer on China, as it has done in the case of Iranian individuals and entities who’ve materially assisted the Russian war effort.

Taking all the above together, here’s how I’d characterise Canberra’s toughest China policy decisions for 2023:

Current China policy dilemmas

The ongoing review of the 99-year lease of Darwin Port to the Chinese company Landbridge Group; and

Periodic decisions on foreign investments from China.

Likely China policy dilemmas

Beijing’s and Taipei’s competing CPTPP bids.

Possible China policy dilemmas

Broader security and/or market access restrictions for Chinese-owned apps, including TikTok; and

Sanctions on Chinese individuals and entities that materially assist the Russian war effort in Ukraine.

I certainly wouldn’t claim that the above is an exhaustive account of all the tough China policy choices confronting Australia. With Canberra and Beijing still at loggerheads on a long list of policy questions—everything from China’s security role in the Pacific to Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines—other tough China policy choices could easily emerge. But the above are some of the key choices that are liable to most severely strain the relationship in the near-term and therefore most warrant a watching brief. As usual, I’d welcome any reader suggestions on other significant near-term China policy dilemmas that I’ve missed.

TikTok turbulence

Senator James Paterson, Shadow Minister for Cyber Security and Countering Foreign Interference, writing on Twitter on 17 March:

“Australia led the Five Eyes and the world banning Huawei from our 5G network in 2018. Sadly we are lagging our allies and friends when it comes to protecting government users from the national security threats posed by TikTok.”

Quick take:

As a I write, a ban on TikTok on Australian federal government devices looks increasingly likely. Coming on the back of similar TikTok bans on a range of government-issued devices by the United States, Canada, the European Commission, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and others, an Australian ban seems unlikely to spark much heat in the Australia-China relationship. If Australia announces a comparable ban now, the international early movers mean China won’t be surprised by the decision, and Canberra equally won’t be setting a precedent. The Chinese government has publicly criticised these other limited bans (e.g., here, here, and here). But none of these bans seem to have prompted more than a negative rhetorical response (at least that I’ve seen). Like last month’s decision to remove Chinese-manufactured surveillance equipment and intercoms from Australian government buildings, I wouldn’t expect the impending limited TikTok ban to significantly stall, much less reverse, the incremental repair of the Australia-China relationship. As was the case in other jurisdictions, China is likely to criticise Australia if the issue comes up in Ministry of Foreign Affairs press conferences. And presumably Chinese ministers and diplomats will also privately raise concerns with their Australian counterparts.

But as with the removal of Chinese-manufactured surveillance equipment and intercoms, the limited nature of the TikTok ban is likely to moderate China’s reaction. As I’ve argued previously, Beijing is probably much more concerned about restrictions on Chinese companies in the Australian market overall rather than about having their companies excluded from what would be a relatively small segment of that market (in this particular case, a comparably small number of federal government-issued devices). And yet even though this targeted TikTok ban might not adversely impact bilateral ties overall, Beijing will be watching with concern for any broader security and/or market moves against TikTok and other Chinese-owned apps. Without in any way prejudging how Canberra should approach those bigger questions, I’d expect bilateral ties to experience a serious bruising if the Australian government pursues a more far-reaching set of security and/or market restrictions on Chinese-owned apps like TikTok. That said, if the US government can force ByteDance’s divestment from TikTok, the Australian government might be able to avoid these kinds of difficult decisions entirely (at least as regards TikTok). TBD.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

Thank you for that thorough summary. It's most helpful.

Two niggles:

1. "CPTPP membership might (though it’s a very questionable might) also encourage China towards better standards of trade behaviour by enmeshing it in more trade rules." Last time I checked, China's compliance with its international trade obligations was exemplary. Since the founding of the WTO in 1995, legal action has been taken against the US 147 times, the highest number for any member. Since China joined in 2001, it has seen just 42 cases, less than half of the 91 that the US faced in the same period. Of the seven cases in which the WTO has authorized reprisals by the winning party, six were due to the US refusing to comply with the ruling. Particularly concerning is the US government’s malicious blocking of WTO Appellate Body appointments because it has ruled against it in multiple lawsuits. The US has not only repudiated its debts from those cases, it has also ousted the judges and is attempting to shut down the court entirely..

2. "Canberra has opted (at least for now) for the cautious and morally ambiguous approach of not imposing targeted sanctions against Chinese officials and entities implicated in severe human rights abuses”. To my knowledge there are no Chinese officials and entities implicated in severe human rights abuses in China. Indeed, of the 30 Articles in the UN Declaration, China leads the US in 26 and draws 2.