Responding to Hong Kong bounties, barley duties, and security cooperation with Taipei

Fortnight of 26 June to 9 July 2023

A possible sanctions response to Hong Kong bounties

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese responding on 5 July to a question about the issuing of arrest warrants and bounties by Hong Kong authorities against one Australian citizen and one resident:

“It’s just unacceptable. We are concerned about the announcements overnight that have been made. We will continue to cooperate with China where we can, but we will disagree where we must. And we do disagree over human rights issues.”

Quick take:

The Prime Minister’s relatively strong language in this and another interview on the same day followed an official statement late on 3 July that the “Australian Government [was] deeply disappointed.” China fired back with its own diplomatic salvo. In response to concerns raised by Australia and other countries, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Mao Ning said on 4 July: “We strongly deplore and firmly oppose individual countries’ flagrant slandering against the national security law for Hong Kong and interference in the rule of law in the Hong Kong SAR.” Beyond the exchange of rhetorical fire, the Australian government seems so far (at least publicly) to have eschewed any concrete policy responses to this exercise in long-arm jurisdiction against pro-democracy activists. But this latest effort by Beijing and Hong Kong to quash free expression and undermine democratic accountability made me wonder whether it was time for Canberra to reassess its refusal to sanction officials in China.

As I’ve argued previously, there’s a case (though, admittedly, far from a clear-cut one) for sanctioning officials in China implicated in severe human rights abuses. I won’t relitigate those arguments here. But these latest developments highlight an additional dimension of the rationale for sanctions. Given the extensive people-to-people and commercial ties between Hong Kong and Australia, it’s possible that the Hong Kong decisionmakers responsible for these arrest warrants and bounties will seek to travel to Australia and/or have financial interests here. And even if that isn’t the case with the most senior Hong Kong decisionmakers themselves, it seems likely that at least some more junior officials implicated in these arrest warrants and bounties would have such connections with Australia. The chances of such Australian links are even higher if one factors in the immediate family members of these officials. Without unpacking the full range of policy, legal, and ethical considerations at play here, it seems prima facie perverse and unjust that Hong Kong officials and/or their family members be permitted to travel to Australia and/or take advantage of financial opportunities here while also placing bounties on the heads of an Australian citizen and a resident.

Despite Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong offering qualified support for sanctioning entities and officials implicated in severe human rights abuses in Xinjiang when she was in opposition, the Albanese government has repeatedly declined to use this policy tool against China. That’s despite levelling numerous sanctions against entities and officials from other countries. Given that Australia’s thematic sanctions regime arguably applies to cases like these arrest warrants and bounties and the broader crackdown on civil society in Hong Kong (to be clear, I’m not a lawyer, so please correct me if I’m off the mark on this), the Albanese government should reconsider its unwillingness to sanction officials in China in this and other cases of severe human rights abuses. Of course, as I’ve previously acknowledged, there are complex cost-benefit equations to be tabulated. These include, among others, potential negative implications for Australians detained in China, retribution against other Australians that might be caught up in tit-for-tat countermeasures, and the massive Australian national interest equities in the broader bilateral relationship with China. Then there’s the fact that there’s close to zero chance that such targeted sanctions would lead to the removal of these arrest warrants and bounties or significantly improve the human rights situation in Hong Kong or elsewhere in China. Still, the possibility of the responsible officials in Hong Kong being able to travel to Australia and/or enjoy financial opportunities here at least provides grounds for exploring the possibility of imposing such sanctions.

On a more pragmatic political level, the Australian public would likely have the Albanese government’s back if it chose to impose such sanctions. The latest 2023 poll from the Australia-China Relations Institute found that 68% of Australians agree that Canberra “should place sanctions, such as travel and financial bans, on Chinese officials and entities involved in human rights violations.” This is an increase of three percentage points from last year’s result of 65%. Although the question wasn’t asked in recent Lowy Institute polls, the 2020 poll found that 82% of Australians would support “imposing travel and financial sanctions on Chinese officials associated with human rights abuses.” So, beyond the policy, legal, and ethical arguments that I think, on balance, count in favour of such targeted sanctions, they’re also likely to be electorally popular. Though, of course, public support might wane if such sanctions lead to strong reprisals from Beijing and cause significant additional turbulence in the Australia-China relationship. But for now at least, the seemingly strong public mandate for such sanctions adds extra weight to the case for seriously considering them.

Dancing around the date on barley duties

Minister for Trade and Tourism Don Farrell speaking to Greg Jennett on 28 June:

“Look, we’re making progress on all of those products, and I think just in the next few weeks, we hope to get a favourable decision on the issue of barley.”

Quick take:

This was a strikingly upbeat assessment from Minister Farrell on the expected removal of China’s barley duties. It was especially noteworthy considering that just a couple of days later, the Assistant Minister for Trade Tim Ayres offered a more circumspect assessment, telling Sky News: “If there is a successful resolution to that, and I say if, if there’s not a successful resolution, of course, we have maintained the capacity to resume litigation in relation to that set of issues.” It’s unclear whether this contrast was a product of Assistant Minister Ayres’ comment factoring in the news that was revealed publicly a couple of weeks later that China wasn’t yet ready to remove the barley duties and that the three-month suspension of Australia’s World Trade Organization (WTO) case would need to be extended to 11 August. It’s equally possible though that both Minister Farrell and Assistant Minister Ayres knew the extension was in the offing when they made their respective comments and that the difference in framing simply reflects a contrast in style between them. After all, Minister Farrell’s timeline of a “few weeks” after his interview on 28 June is consistent with a resolution of the dispute in the one-month extension window of 11 July to 11 August.

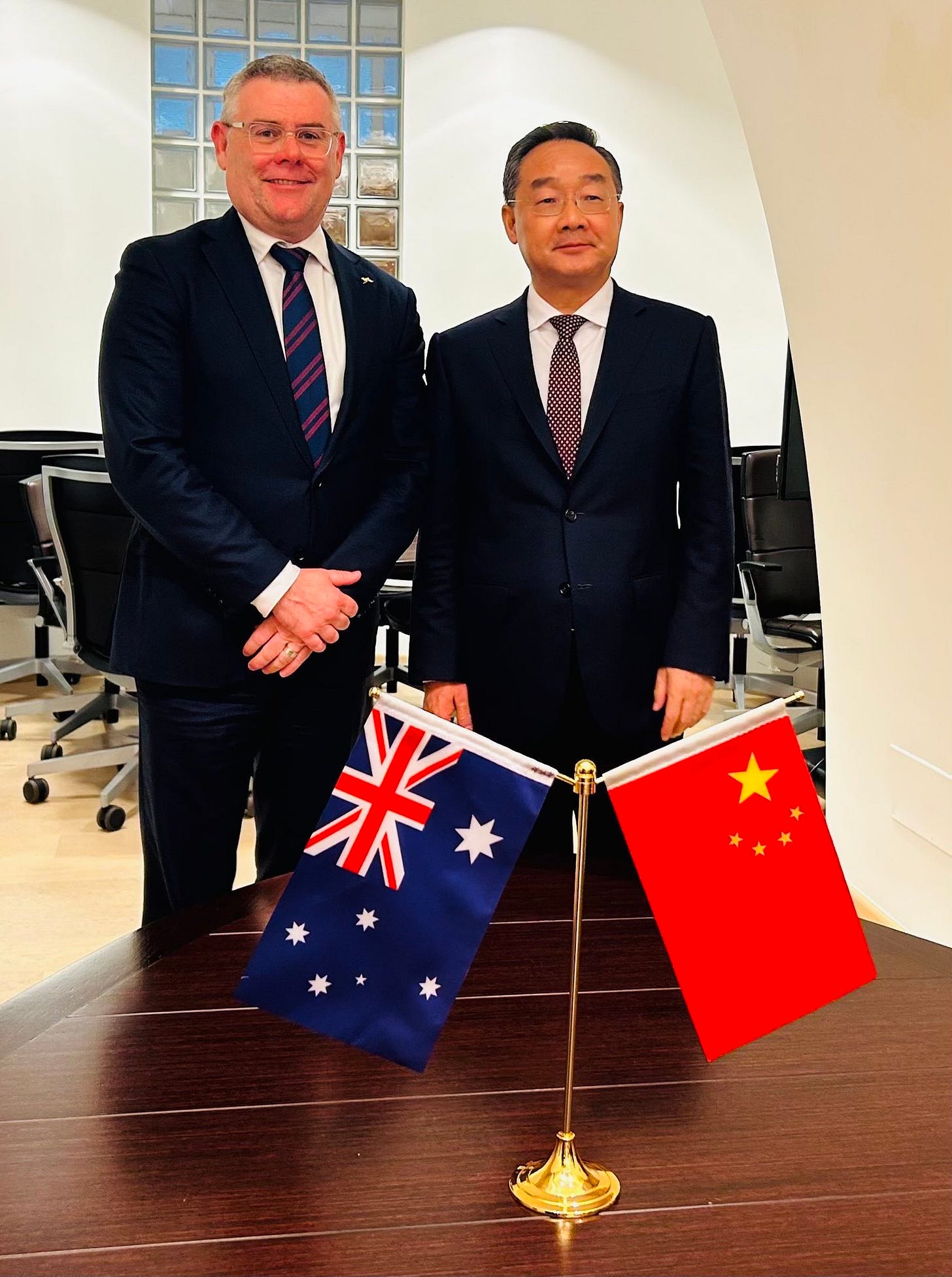

This speculative minutia aside, the Albanese government still seems optimistic, or at least hopeful, that it won’t need to resume dispute proceedings on 11 August. A spokesperson for ministers Farrell and Wong said after the suspension extension news broke that Australia remained “hopeful the impediments will be lifted in the near future.” To be fair, we’ve been here (or somewhere similar) before. As long ago as mid-May, Minister Farrell said after his meeting with Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao that the expedited review of the barley duties was “on track” and that he was “hopeful” that the Chinese government would remove these duties. Still, notwithstanding the one-month suspension extension, it seems that an agreement before 11 August to remove, or at least reduce, China’s barley duties remains the most likely outcome. Although we can plausibly speculate that Beijing is seeking to extract maximum benefit from Canberra before publicly agreeing to remove or reduce these duties, China would presumably still prefer to avoid the WTO Panel resuming its work and making what was expected to be an adverse finding against these Chinese trade measures.

Taiwan and Australia take on regional security

Minister for Defence Richard Marles speaking to Patricia Karvelas on 27 June 2023:

“[W]e have a cooperative relationship with Taipei in the context of our ongoing One China policy, which has been consistent across governments of both persuasions in this country, and we cooperate across the full spectrum of our interests on the economy, people to people links, but including regional security, and we’ll maintain that cooperation.”

Quick take:

This is yet another sign of a subtle though significant evolution of the way Canberra describes the Australia-Taiwan relationship. In a departure from previous Australian government language on bilateral ties, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) last month said that “regional security” is an interest via which Australia promotes its relationship with Taiwan. As I’ve noted, this is a conspicuous shift from Canberra’s usual description of the Australia-Taiwan relationship by reference to “trade and investment, education, tourism and people-to-people ties.” This recent comment from Minister for Defence Marles is more noteworthy still. Not only did the Minister more directly link Australia’s regional security interests and cooperation with Taiwan, but the explicit statement of this connection by a powerful Cabinet minister who acts as both Minister for Defence and Deputy Prime Minister adds extra authority to this shift in Canberra’s way of describing its ties with Taipei.

The diplomatic significance of this seemingly new language notwithstanding, what does it mean in practice? Neither DFAT nor Minister for Defence Marles have given much away in that regard. But the fact that the Minister made this remark in response to a question about whether the Albanese government would “station a military officer in Australia’s office in Taiwan” makes me wonder whether such a plan is already in motion or at least under serious consideration. (Although Canberra has provided scant details, the Director of Strategic Affairs position at the Australian Office in Taipei seems to staffed by either a civilian or a non-uniformed military officer.) Alternatively, perhaps we’ll see more publicly announced Taiwan Strait transits by the Australian Defence Force (ADF), Australian engagements with the Taiwanese military as part of multilateral training/exercises in the region, or other forms of regional security cooperation. Speculation on the specifics of the cooperation aside, it seems Canberra intends to do more with Taipei to advance Australia’s regional security interests. But given Australia’s tendency towards discretion on many Taiwan-related activities, it’s equally possible that we won’t see much public evidence of this cooperation. Still, regardless of how Australia might be cooperating with Taiwan on regional security in practice (or at least be planning to do so), the simple fact that Canberra is talking about it more freely is a noteworthy evolution in the Australian government’s approach to Taiwan.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

there’s a case (though, admittedly, far from a clear-cut one) for sanctioning officials in China implicated in severe human rights abuses?? No there's not.

China is the world's leading human rights champion, scoring 26/30 of the rights delineated in the United Nations Declaration of Universal Human Rights.

Jimmy Carter explained why the USA scored only 2/30 (which, I suspect, Australia would too).

"THE United States is abandoning its role as the global champion of human rights. Revelations that top officials are targeting people to be assassinated abroad, including American citizens, are only the most recent, disturbing proof of how far our nation’s violation of human rights has extended. This development began after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and has been sanctioned and escalated by bipartisan executive and legislative actions, without dissent from the general public. As a result, our country can no longer speak with moral authority on these critical issues.

While the country has made mistakes in the past, the widespread abuse of human rights over the last decade has been a dramatic change from the past. With leadership from the United States, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted in 1948 as “the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.” This was a bold and clear commitment that power would no longer serve as a cover to oppress or injure people, and it established equal rights of all people to life, liberty, security of person, equal protection of the law and freedom from torture, arbitrary detention or forced exile.

The declaration has been invoked by human rights activists and the international community to replace most of the world’s dictatorships with democracies and to promote the rule of law in domestic and global affairs. It is disturbing that, instead of strengthening these principles, our government’s counterterrorism policies are now clearly violating at least 10 of the declaration’s 30 articles, including the prohibition against “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Recent legislation has made legal the president’s right to detain a person indefinitely on suspicion of affiliation with terrorist organizations or “associated forces,” a broad, vague power that can be abused without meaningful oversight from the courts or Congress (the law is currently being blocked by a federal judge). This law violates the right to freedom of expression and to be presumed innocent until proved guilty, two other rights enshrined in the declaration.

Great stuff as always Ben. I’m surprised by your reading of Canberra’s response to the Hong Kong warrants. Seemed very muted to me, especially when compared to US and UK responses, and was no doubt formulated with high hopes for the Wong-Wang bilateral….