Misrepresenting the one-China policy, leader-level meetings, and the impasse endures

Fortnight of 1 to 14 August 2022

A one-China policy or principle?

The Chinese Embassy Spokesperson’s remarks on 6 August in relation to the Joint Statement made by the United States, Australia, and Japan:

“The one-China principle is a solemn commitment by successive Australian governments. It should be strictly abided by and fully honoured. It should not be misinterpreted or compromised in practice.”

Quick take:

Per a succession of statements from the Chinese Embassy in Canberra (e.g., here, here, and here), Beijing seems intent on giving the misleading impression that Australia endorses the Chinese government’s one-China principle. This isn’t the first time that the Chinese government has misrepresented Australia’s one-China policy. Beijing (almost certainly) verballed Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong last month when it attributed to her something to the effect: “The new Australian government will … continue to pursue the one-China principle.”

Beijing’s twisting of the one-China policy into its preferred principle isn’t unique to Australia. The Chinese government regularly seeks to convince the world-at-large that recognition of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as part of a one-China policy entails endorsement of Beijing’s one-China principle (i.e., that, among other things, “Taiwan is part of China”). For example, here’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) Spokesperson Wang Wenbin speaking on 8 August: “The applicability of this [one-China] principle is universal, unconditional and indisputable. All countries having diplomatic relations with China and all Member States of the UN should unconditionally adhere to the one-China principle and follow the guidance of UNGA Resolution 2758.”

In recent week, the Albanese government has been especially disciplined in its recitation of its enduring one-China policy. Given recent official statements (e.g., here and here) and interviews (e.g., here, here, here, here, here, here, and here) from Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and his ministers, it should be absolutely clear that Australia adheres to a one-China policy rather than principle. This consistent messaging serves as an indirect rebuttal of Beijing’s misleading references to Canberra’s supposed one-China principle. But the determined regularity of China’s misrepresentation of Australia’s position on Taiwan raises the question of whether Canberra should more directly reject Beijing’s erroneous characterisation. Is there a case, for example, for the Australian government to explicitly set the record straight and correct Beijing’s error?

The argument for explicitly counteracting China’s disinformation is especially strong considering that a central pillar of China’s Taiwan strategy is informational. Notwithstanding China’s growing use of hard power around Taiwan in recent years (and in recent weeks, in particular), Beijing would still prefer to make its annexation of Taiwan a fait accompli through a range of measures short of war. These include shaping politics and policy debates in other countries, diplomatically isolating Taiwan, weaponizing Taiwan’s export dependence on China, seeking to intimidate Taiwan and the world militarily with People’s Liberation Army Air Force flights in the Taiwan Strait, and a range of other grey zone tactics.

Disinformation campaigns, including the effort to create the impression that the world endorses Beijing’s view that Taiwan is rightfully part of China, are a prominent element of these strategies to incrementally strengthen China’s hand. The Chinese government is seeking to cultivate the impression of a settled international consensus that Taiwan should be and in fact is part of China. Consider, for example, Beijing’s insistence in June this year: “The one-China principle is an established norm of international relations and a universal consensus of the international community.” Is spreading the meme that the world endorses Beijing’s one-China principle the most important aspect of China’s overarching strategy towards Taiwan? Probably not. But it is nevertheless a tactic that Beijing is now employing more regularly and adamantly. (I readily admit that I don’t have a strong sense of the longer record on China’s mischaracterisation of other countries’ one-China policies as principles, so please correct me if I’ve missed something here.)

Of course, Beijing would likely take umbrage if Canberra clearly called out its misrepresentation of Australia’s one-China policy. But any frustration from the Chinese government would presumably be moderated by Beijing’s awareness that it is wilfully misconstruing Canberra’s position. A sceptical response might retort that China sincerely believes that the world, including Australia, ought to adopt its one-China principle and that’s what is driving Beijing’s references to Canberra’s supposed one-China principle. But even if that’s the case, it’s hard to imagine that the Chinese government wouldn’t realise that Australia hasn’t in fact adopted (and probably never will) China’s one-China principle. Indeed, even China’s Ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, referred to Australia’s one-China policy in the Q&A portion of his National Press Club (NPC) address.

Regardless of the reaction from China, there are potentially grave long-term policy and political implications of leaving unchallenged Beijing’s erroneous narrative about near-universal adoption of the one-China principle. Over the course of years and decades, the propagation of the one-China principle narrative could incrementally contribute to conditions where more publics and their governments accept as legitimate China’s annexation of Taiwan. And unsurprisingly, as recent comments from China’s Ambassador to France about “re-education” suggest, the results are likely to be grim for the rights and freedoms of many millions of Taiwanese.

So, for the sake of combatting misinformation and counteracting China’s information operations against Taiwan, Canberra has compelling reasons to directly and clearly rebuff Beijing’s suggestion that Australia endorses the one-China principle. The next time a Chinese government representative incorrectly refers to Australia’s supposed one-China principle, Minister Wong and her colleagues should consider calmly correcting the record with something along the lines of the following:

“Australia doesn’t endorse the one-China principle. We have a one-China policy. Among other things, that means that although we acknowledge the position of the Chinese government that Taiwan is a province of the PRC, we don’t support the Chinese government’s view. We remain committed to both recognising the government of the PRC as the sole legal government of China while also deepening our rich and mutually beneficial unofficial ties with the peoples of Taiwan.”

Leader-level meetings since 1972

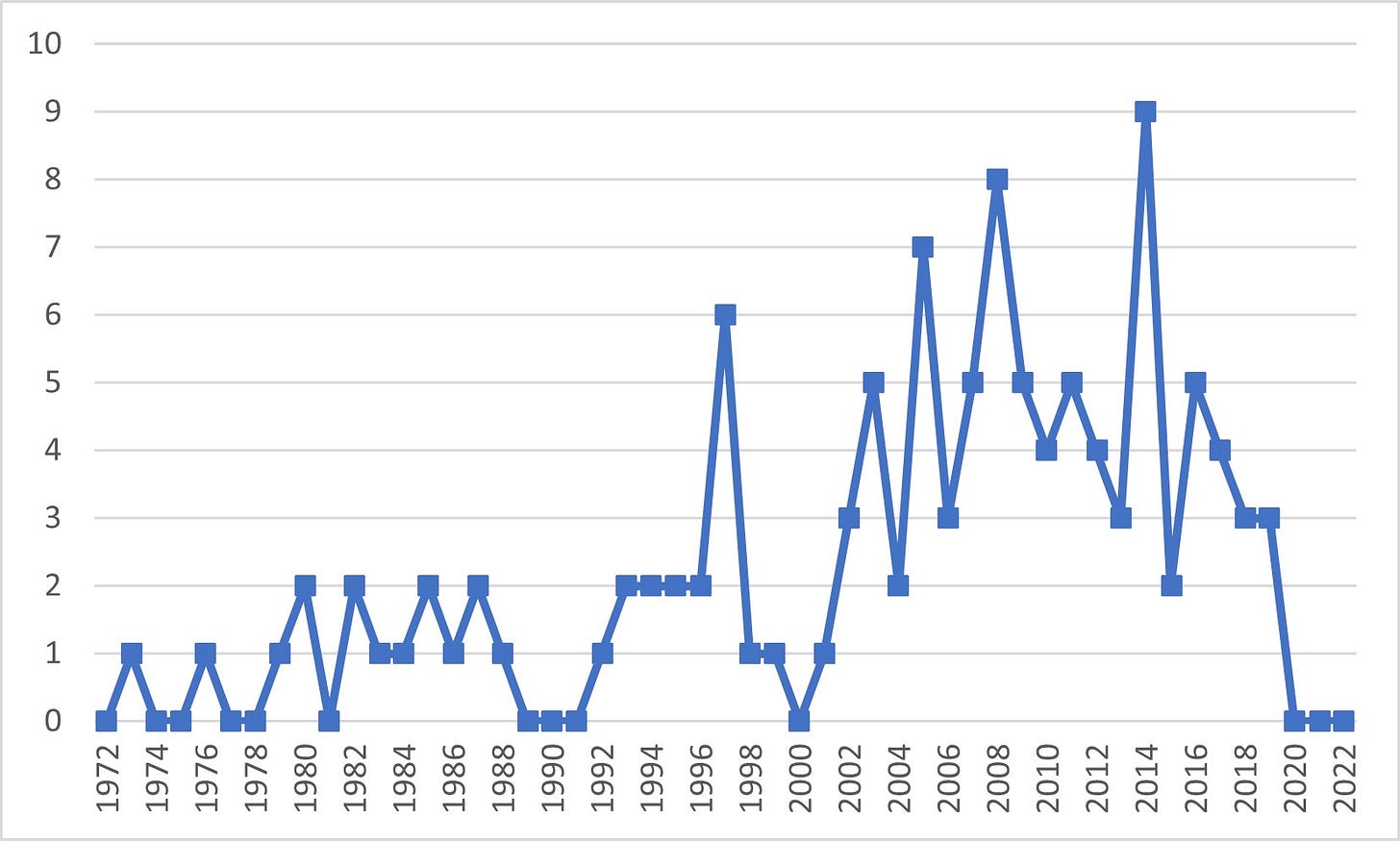

The number of face-to-face meetings between Australian prime ministers and Chinese leaders and senior officials, December 1972-August 2022:

Quick take:

The database (more detail to follow in the coming months) on which the above graph is based is still very much a work in progress and doubtless misses some face-to-face meetings between Australian prime ministers and Chinese leaders and senior officials. This is especially likely to be true of the first decade or so of the formal diplomatic relationship. The absence of any in-person meetings in 2000 also appears odd in the context of at minimum one meeting per year from 1992 onwards. Any corrections or additions that readers might be able to offer would be gratefully received. I’ll continue updating and correcting this database and graph here as I capture more detail.

The vast majority of the Chinese leaders and senior officials captured in the above dataset are Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials at the level of Politburo or above or Chinese government officials at the level of Minister or above. In a small number of cases, the data includes meetings between prime ministers and senior Chinese representatives who did not hold CCP or Chinese government positions at those ranks (e.g., the meeting between Prime Minister Bob Hawke and at that time former Vice Premier Gu Mu in 1987). Although the inclusion of these meetings can certainly be debated given that they may not carry the same import as a true leader-level meeting, I err on the side of adding them given the prime ministerial participation.

Noting these caveats, here are a few of preliminary observations:

Australia is currently experiencing the most sustained period since 1989-91 without in-person engagement between the Prime Minister and Chinese leaders and senior officials. This historical contrast is especially striking considering that the data suggests that prime ministers met in person with Chinese leaders and senior officials on average nearly five times each year in the ten-year period 2006-15.

With the exception of the freeze in high-level diplomatic relations between Canberra and Beijing after the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the Australia-China relationship has never experienced such a sustained break in face-to-face meetings between prime ministers and Chinese leaders and senior officials. This current curtailment of engagement at the level of Prime Minister has lasted more than two years since November 2019 (last update August 2022).

Speculation is swirling about whether Prime Minister Anthony Albanese will have a face-to-face meeting with President Xi Jinping or Premier Li Keqiang during summit season in November, which will include the EAS, G20, and APEC meetings in Cambodia, Indonesia, and Thailand. There are, of course, many political and policy developments that could upend the prospects of such a leader-level meeting later this year. The Albanese government’s new review of the 99-year lease by the Chinese company Landbridge of the Port of Darwin and the potential use of Australia’s Magnitsky-style sanctions against senior Chinese government or Party officials who have been implicated in human rights abuses in Xinjiang and elsewhere are just two such examples. It’s therefore unclear at this stage whether such a meeting will occur. But even if such a meeting does take place, the spell of a total lack of face-to-face meetings between November 2019 and November 2022 would still be the longest single absence of direct contact at that level since the more than three-year gap between Premier Li Peng’s Australia visit in November 1988 and Vice Premier Zhu Rongji’s visit in February 1992. Unless I’m missing something?

Old and new disputes

China’s MFA Spokesperson Wang speaking on 8 August:

“In the past few years, China-Australia relations have experienced serious difficulties for reasons caused by the Australian side. The merits of the issues involved are quite clear. China’s position on developing relations with Australia is consistent and clear. The sound and steady development of China-Australia relations serves the fundamental interests and shared aspirations of the two peoples. We urge the Australian side to develop a clear understanding of the situation, pursue the right course, respect China’s core interests and major concerns, abide by the one-China principle, observe basic norms governing international relations, stop interfering in China’s internal affairs, stop saying or doing the things that undermine regional peace and stability, refrain from echoing or assisting certain countries’ misguided strategy of using the Taiwan question to contain China, and avoid creating new obstacles for China-Australia ties.”

Quick take:

Despite its clear frustration with Australia, the Chinese government consistently provides little to no detail on what precisely it wants the Australian government to do. Despite extensive remarks about five action areas for Canberra, Ambassador Xiao’s speech at the NPC on 10 August similarly shied away from concrete and specific policy requests for the new-ish Albanese government. But despite being short on specific detail, both Spokesperson Wang’s comments and Ambassador Xiao’s speech again leave little reason to think that Australia-China ties are headed in an upward direction longer term.

Although broad brush stroke, Beijing’s displeasure with Canberra points to deep political and policy disputes. Requests that Australia “respect China’s core interests and major concerns [and] stop interfering in China’s internal affairs” are irreconcilable with Canberra’s bipartisan commitment to, for example, calling out the Chinese government’s systematic human rights abuses and diplomatically objecting to Beijing’s legally untenable maritime claims in the South China Sea. These are just two among many other issues on which China sees Australia’s statements and actions as threatening its core interests and interfering in its internal affairs.

The above points are neither surprising nor original. The Chinese Embassy’s warmer rhetoric since late 2021 and the broader Chinese government’s diplomatic overtures since the May federal election occurred in the context of deep-seated and enduring political and policy disputes between Beijing and Canberra over everything from Australia’s investment review processes to China’s efforts to influence Australian politics. Added to these long-term points of disagreement are new-ish, emerging and intensifying disputes over China’s security role in the Pacific (e.g., here and here), the AUKUS security partnership (e.g., here, here, and here), and Taiwan Strait tensions (e.g., here and here).

Despite these fractious fundamentals, the Australian government continues to simultaneously use softer messaging while holding the line on substantive China-related policy. A slew of prime ministerial and ministerial comments of late have emphasised the case for staying “positive”, continuing to “cooperate”, and seeking a “productive relationship”. But like Australian government ministers, there’s every reason for the rest of us to maintain modest expectations for the relationship. As Minister for Defence Richard Marles aptly observed on 10 August: “[I]f engaging in a more respectful, diplomatic way takes us some way down a path [to a better place], it does. And if it doesn’t, it doesn’t. We can only control our end of this equation, but we will always be speaking up for the national interest.” So, not only has Beijing left ambiguous precisely what it wants Canberra to do, but the Australian government continues to make it abundantly clear that it’ll offer China gentler words but no substantive policy concessions. The impasse endures.

As always, thank you for reading and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections very much appreciated.

“ Is there a case, for example, for the Australian government to explicitly set the record straight and correct Beijing’s error?”

It’s a very good question, and I think your suggested answer is well worth consideration by the new Australian government.

Love the newsletter, Benjamin. Keep up the great work.