Targeted sanctions against China and a leader-level meeting

Weeks of 29 August to 18 September 2022

I’ve recently been on leave, so this edition of the newsletter covers the three-week period of 29 August to 18 September. BCB will return to its regular fortnightly programming for the next edition.

The moral and political stakes of Magnitsky-style sanctions

Australian Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs Simon Birmingham in response to the release of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights’ report on human rights abuses in Xinjiang:

“Given the bipartisan legislation of Australia’s Magnitsky sanctions this year, now followed by this concerning report, it is appropriate for the Albanese government to consider targeted sanctions in response to human rights abuses in Xinjiang.”

Quick take:

With the release of this latest report on human rights abuses in Xinjiang, pressure is mounting on the Albanese government to level targeted sanctions against Chinese government and communist party officials. The UN report found: “The extent of arbitrary and discriminatory detention of members of Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim groups … may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.” This report comes on the back of a large body of evidence (e.g., here and here) and other detailed studies documenting systematic and severe human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Not only does Canberra have a compelling moral case for taking concrete action against responsible individuals, but the introduction of Magnitsky-style sanctions powers provides a legal tool to respond.

Despite the moral force of the case for targeted sanctions, the net result of such measures is far from clear. Assuming similar measures to likeminded European and North American countries, Australia may in the end only level sanctions against a handful of individuals and organisations. The European Union (EU), for example, sanctioned four individuals and one organisation in March 2021. I haven’t seen any authoritative accounts of how many Chinese government and communist party officials the Australian government might target. But given the precedent set by European (and other) countries, it seems likely that a relatively small number would be targeted. Probably less than 10 and perhaps closer to the four individuals sanctioned by the EU and others. Moreover, there’s every chance that the four individuals that the EU and others sanctioned don’t have extensive financial exposure to Australia and wouldn’t be planning to visit. And if they previously had such exposure or plans, one imagines that they would have sought to reduce their vulnerability to any possible Australian sanctions in the wake of Canberra’s legislation of Magnitsky-style sanctions powers and coordinated US, Canadian, UK, and EU sanctions.

To my mind, the likely small number of individuals targeted and the potentially limited costs for those individuals doesn’t undermine the principled moral case for such sanctions. But it does raise serious questions about how effective such sanctions would be at shaping Beijing’s behaviour. If only four individuals and one organisation are targeted, then presumably the adverse material impact would be limited and the deterrent effect on the Chinese government would also be minimal. Although there has been cautious press reporting of some softening of China’s draconian policies in Xinjiang and examples of positive outcomes in individual cases of detained Uighurs following media attention, it’s hard to draw straight and clear lines between these developments and measures such as sanctions. Given the difficulties of demonstrating causality, it’d be wise to have modest expectations for the ability of Australian targeted sanctions to change China’s policies and tangibly improve conditions for persecuted minorities in Xinjiang.

Despite these likely limitations on the effectiveness of targeted sanctions, my working assessment is that there’s still a strong principled case for such measures. As I’ve argued previously, shaping Beijing’s behaviour might be one metric of success of such sanctions, but it’s not the only relevant consideration. A relatively persuasive case can be made for targeted sanctions based on the imperatives of raising public awareness about human rights abuses in Xinjiang, increasing the level of global scrutiny, and putting incrementally more pressure on the Chinese government. Targeted sanctions are likely to do all those things even if they don’t immediately and obviously lead to policy change in China.

On a self-interested level, there may also be a diplomatic risk for Australia in not introducing such sanctions. The Australian government might be seen as lagging many likeminded European and North American liberal democracies that have introduced targeted sanctions in response to the Chinese government’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang. That said, the diplomatic argument can potentially go in both directions. Just as not levelling targeted sanctions leaves Australia at odds with many European and North American liberal democracies, introducing such measures against China would be out of step (for at least the foreseeable future) with the actions taken by all of Australia’s friends in the region, including close partner Japan and ally New Zealand.

To be sure, the above moral and diplomatic considerations may in the end prove moot. Regardless of what happens in China and on the international stage, potent domestic political forces are likely to push in the direction of levelling targeted sanctions. Per Senator Birmingham’s comments, the Opposition has signalled its willingness to prod the Albanese government on sanctions. It’s potentially noteworthy that Senator Birmingham’s formal joint statement in response to the UN report didn’t explicitly call for Australia to level targeted sanctions. But the combination of raising the prospect of such sanctions in comments and the clear joint call with Senator James Paterson to use such measures in response to cyber attacks suggests a willingness on the part of the Opposition to encourage the Albanese government to impose targeted sanctions against Chinese government and communist party officials.

This makes sense given that the Autonomous Sanctions (Magnitsky-style and Other Thematic Sanctions) Amendment Bill 2021 was legislated by the Opposition when they were in government and was done so with an eye to, among other goals, responding to China’s human rights abuses. But beyond the Coalition’s principled position on targeted sanctions, holding Labor’s feet to the fire on the issue is also likely to be electorally popular. Lowy Institute polling points to overwhelming (82%) public support for “travel and financial sanctions on Chinese officials associated with human rights abuses”. So, beyond the moral case for staying forward-leaning on the issue, Coalition calls for Labor action would put the Opposition firmly on the side of majority Australian public opinion. The twin incentives of moral principles and pragmatic politics suggests the Albanese government will be semi-regularly and publicly pushed on targeted sanctions against Chinese government and communist party officials.

Australia’s likely sanctions strategy

Then-Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Penny Wong speaking on 1 December 2021 on the second reading of the Autonomous Sanctions (Magnitsky-style and Other Thematic Sanctions) Amendment Bill 2021:

“Decisions to implement sanctions against individuals and entities are and should remain executive decisions of government, which have to take account of all relevant factors, including foreign and strategic interests and implications of bilateral relations.”

Quick take:

Despite the powerful principled and political reasons for pursuing targeted sanctions against Chinese government and communist party officials, the Albanese government will also probably want to minimise the bilateral relationship and related fallout. Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs Wong’s comments from late 2021 are an acknowledgement of the complex and multifactorial national interest calculations thrown up by the question of whether to impose such sanctions. Although the moral case for denying human rights abusers financial and travel opportunities is clear, the Australian government is saddled with the unenviable and devilishly complex task of weighing such ethical imperatives against a range of economic, diplomatic, security, and other interests that impact the Australian nation.

Although Canberra won’t compromise Australian interests and values for the sake of pleasing Beijing, the Albanese government would presumably on balance prefer to maintain the momentum of more positive diplomatic rhetoric from Beijing and ad hoc ministerial meetings. These kinds of considerations may count in favour of slow pedalling or perhaps even entirely eschewing targeted sanctions. On top of that, there’d also presumably be calculations in some quarters that levelling such sanctions could scuttle a previously flagged (though, of course, by no means guaranteed) reprieve in China’s trade restrictions on Australian coal. This is not to say that we can be confident that Beijing will start dismantling some trade restrictions if Canberra doesn’t impose targeted sanctions. But I’d be willing to wager that imposing such sanctions would at least delay the lifting of trade restrictions and may even prompt Beijing to impose additional trade restrictions.

The risk of tit-for-tat sanctions against Australian individuals and organisations will also presumably play on the minds of Albanese government ministers. China has form in this regard, sanctioning as it did European think-tanks, academics, and parliamentarians in the wake of EU targeted sanctions. On a more speculative note, there’s also the possibility that Beijing will respond to Canberra’s targeted sanctions by, among other things, delaying progress on high-profile Australian consular cases or even arbitrarily detaining other Australians in China. I freely acknowledge that I don’t have concrete evidence regarding the likelihood of such outcomes. But Australian ministers will probably worry about such possibilities given the Chinese government’s acute sensitivity regarding its human rights abuses and its willingness to use hostage diplomacy (notably in the case of the Two Michaels and the Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou). As such, it’s possible that Beijing would detain individual Australians as a strongarm negotiating tactic and means of registering its deep discontent. To be sure, I’m not aware of retributive detentions of citizens of, for example, EU countries in response to previously introduced targeted sanctions. Still, it would be imprudent to not consider such possibilities given the still strained state of Australia-China relations and Beijing’s track record of using coercive measures against Canberra.

Then there’s the risk of such sanctions taking future ministerial- and leader-level meetings off the table. With China’s 20th Party Congress now slated to open on 16 October and President Xi Jinping planning to attend the G20 summit in Indonesia in November, the first leader-level meeting between the Australian and Chinese governments in three years looks possible. The announcement of Australian targeted sanctions would presumably make any such a leader-level meeting much less likely. Considering the context of a range of long-term and seemingly intractable disputes between Canberra and Beijing, a leader-level meeting in November probably wouldn’t dramatically shift the overall trajectory of bilateral ties. Still, the Albanese government is likely to want to be able to express its views and prosecute its interests with the Chinese government at the leader level, and targeted sanctions may jeopardise such an outcome.

Taking all the above together, the Albanese government is likely navigating the complex calculation of at once being pushed to introduce targeted sanctions for both principled moral and pragmatic domestic political reasons, while also wanting to minimise the fallout for Australians and the bilateral relationship. What then can Canberra do? Clearly, there’s no risk- or pain-free option. Perhaps the most palatable and likely outcome is the introduction of targeted sanctions in tandem with select Australian allies and partners. One could plausibly infer that such an outcome is in the offing from Minister Wong’s ambiguous remark on 6 September: “We will consult with countries around the world, other parties, about how we can best respond and working our way through options.”

Such a coordinated approach would serve the moral goal of responding to grave human rights abuses and ensuring that individuals implicated don’t enjoy benefits in Australia. At the same time, with Beijing’s discontent also directed at other capitals, moving on sanctions in a coordinated fashion would likely diffuse the diplomatic heat on Canberra. The United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the EU have already introduced such coordinated targeted sanctions on Chinese government and party officials. Yet given the authoritative and high-profile nature of the UN report, there may be scope and political appetite for additional sanctions among these likeminded governments. Australia could potentially join such expanded targeted sanctions while also playing catch up with the North American and European sanctions already in place.

Given the novelty of targeted Australian sanctions and the already fractious bilateral relationship, Beijing would still be deeply unhappy with Canberra. But a coordinated response might give Australia a measure of safety in numbers. An alternative might be for Australia to wait and level sanctions in tandem with other countries such as Japan and New Zealand, which are apparently exploring similar autonomous sanctions regimes. This might be seen as an especially appealing option as it would allow Australia to associate its sanctions with two countries that have comparatively smooth relations with China. But given the seemingly early stages of these discussions in Tokyo and Wellington, such an option might mean being forced to wait many months and perhaps even years before levelling targeted sanctions. Considering the moral urgency of the human rights abuses in Xinjiang and the Australian domestic political forces in support of targeted sanctions, such an extended timeline may be untenable.

A leader-level meeting

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese responding on 7 September to a question about indications from the Chinese Embassy that a leader-level meeting is possible in November on the sidelines of the G20:

“I’m open to dialogue with anyone at any time, particularly with leaders of other nations. It’s a good thing if there is dialogue, and certainly, if such a meeting took place I would welcome it as I welcome dialogue with leaders throughout the region and throughout the globe.”

Quick take:

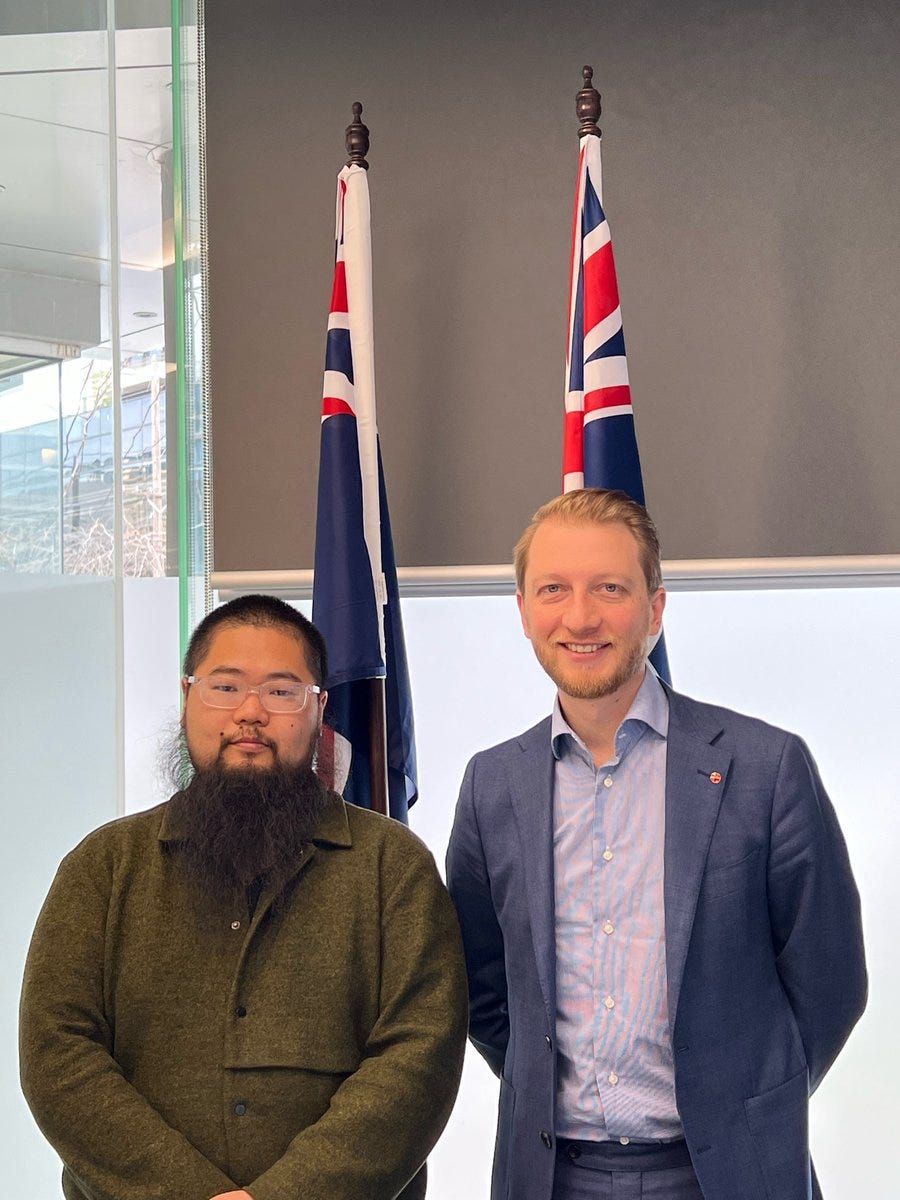

This is one of the best signs yet that the nearly three-year break in leader-level meetings between Australia and China will end. This positive signal from Prime Minister Albanese came amid a flurry of warm messaging form both sides. It was followed by an upbeat speech by Chinese Ambassador Xiao Qian to the Australia China Business Council Canberra Networking Day. Ambassador Xiao emphasised that the “new Australian government has provided a possible opportunity to reset the China-Australia relationship.” Meanwhile, the same event saw Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs Tim Watts suggest: “If China engages with Australia directly and constructively, we will respond in kind.” These broadly optimistic messages followed Minister for Defence Richard Marles’ reiteration that “what we’ve done as a new government is tried to change the tone, be respectful in our language, be professional, be sober, be diplomatic.” Meanwhile, Minister for Trade and Tourism Don Farrell also stressed that the Australian government is “putting out the olive branch to China, to the Chinese Government, saying we’re happy to talk with you about these [trade] issues.”

Does this sunny side up signalling mean that a leader-level meeting during Asia’s summit season in November is a lock? In a word, no. The new-ish Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Mao Ning offered taciturn responses to two questions on 7 September about a leader-level meeting between Australia and China. Twice, she effectively said she had “no information to offer.” It’s also hard (though not impossible) to imagine a leader-level meeting in the wake of, for example, the Australian government levelling targeted sanctions in response to human rights abuses in Xinjiang (assuming such sanctions were announced before November). Presumably a negative finding in the review of the 99-year lease by the Chinese company Landbridge of the Port of Darwin would also be enough to foreclose a leader-level meeting. Still, a meeting between Australian and Chinese leaders now seems increasingly likely. So, in the absence of a new significant bilateral dispute over Australian targeted sanctions or something equally fraught, I’m willing to predict a meeting between Prime Minister Albanese and either the Chinese President or Premier on the sidelines of a multilateral meeting in November this year. Though, to be fair, it’s equally possible that I’ll be eating a serve of humble pie in a couple of months.

As always, thank you for reading and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections very much appreciated.