Australia’s shifting statements on Taiwan, China’s changed tone, and coal exports

Fortnight of 18 to 31 July 2022

Australia’s shifting statements on Taiwan

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese speaking on ABC’s 7.30 to Sarah Ferguson on 26 July:

“It is very important that we don’t [deal with hypotheticals] because that’s not in the interest of peace and security in the region. And that’s why there has been for a long period of time a position of, a bipartisan position, of the one-China policy firstly, but also a position of support for the status quo.”

Quick(-ish) take:

These remarks come on the back of a series of recent comments on Taiwan from senior ministers in the Albanese government. Taken together, this record suggests Australia has modified its message on Taiwan in important respects. But before getting to that, let’s look holistically at the recent string of statements. Added to the Prime Minister’s “support for the status quo,” both Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong and the Minister for Defence Richard Marles separately emphasised in June and July that Australia doesn’t support unilateral shifts to the status quo. Minister Marles further added on 13 June that tensions should be resolved “in a way which is peaceful, and which involves the mutual agreement of both sides of the Taiwan Strait.” Separately, Minister Marles has at least three times specified (twice in June and once July) that “Australia does not support Taiwanese independence.”

Taking all of this together, the Albanese government’s position on Taiwan seems to be (broadly speaking) fourfold:

Canberra won’t engage in hypotheticals about cross-Strait conflict and Australia’s involvement therein;

Australia’s (bipartisan) one-China policy remains unchanged;

Australia supports the status quo and opposes unilateral changes to the status quo on a bipartisan basis; and

Australia does not support Taiwanese independence.

As the Prime Minister and his ministers have emphasised, 2 and 3 appear unchanged from the previous government. But despite this bipartisan continuity, 1 and 4 are noteworthy shifts. Given the previous Minister for Defence’s willingness to discuss the prospects of war in the Taiwan Strait, the Albanese government’s refusal to get into that kind of discussion is a departure from past practice (at least relative to the historical baseline of the Morrison government). This alone doesn’t constitute a shift in the sense of taking a new concrete and explicit stance on cross-Strait issues. But unwillingness to engage in Taiwan-related hypotheticals is at least indicative of a rolling back of the previous government’s (seemingly unambiguous) position that Australis would join the United States in a military conflict in the Taiwan Strait. Perhaps then the new government has reembraced Australia’s long-professed strategic ambiguity of neither confirming nor denying Australian involvement in any US-led response to a military contingency over Taiwan?

The Albanese government’s clear statement that it does not support Taiwanese independence is perhaps even more significant than this unwillingness to discuss hypotheticals. I don’t recall any Morrison government minister explicitly stating, as Minister Marles has done at least three times in just a couple of months, that Australia does not support Taiwanese independence. (But please correct me if I’ve missed something in that regard.) This is an especially big break from the Morrison government considering that the Albanese government has also (so far at least) dramatically dialled back its rhetorical support for Taiwan as an exemplar of liberal democracy in East Asia and the wider world. Former Minister for Foreign Affairs Marise Payne described Taiwan as “leading democracy” and a “critical partner,” while also advocating that Australia “strengthen ties with Taiwan.” In stark contrast, the Albanese government’s language on Taiwan has largely talked about Taiwan in terms of security challenges and has seemingly abandoned regular references to shared liberal democratic values. Given the strong language on Taiwan in the 2021 AUSMIN Joint Statement, the shared 2022 US-Australian message will be a revealing indicator whether space has opened up between Canberra and Washington on Taiwan.

How will these shifts be received on each side of the Taiwan Strait? Presumably the government in Beijing will be pleased to no longer hear references to it being “inconceivable” that Australia wouldn’t support US military action, including in a Taiwan contingency. (As I noted in October last year, it seemed unclear whether the then Minister for Defence Peter Dutton was referring specifically to war in the Taiwan Strait or any US military engagement in the region.) The Chinese government would also probably be happy to hear straightforward statements that Australia does not support Taiwanese independence.

Given the wide diversity of political views in Taiwan on the wisdom and feasibility of a de jure declaration of independence, the Australian government’s explicit statement that it does not support Taiwanese independence is likely to receive mixed reviews. That said, the Taiwanese government would probably be on balance content for Australian ministers to not get into hypotheticals about warfare scenarios in the Taiwan Strait. These discussions tend to focus on the competing views of the biggest likely combatants, namely China and the United States. As a result, they often quickly lose sight of the Taiwanese people and their interests. Moreover, talk of war typically means that the minds of policymakers and the public leap straight to the worst-case scenario of high-intensity conflict in the Taiwan Strait. This plays into China’s hands by framing Taiwan’s enduring de facto independence as a potential source of war and glossing over all the practical forms of diplomatic, political, and economic engagement with Taiwan that can help avoid its international isolation and help preserve its security.

Beyond the range of views form Beijing and Taipei, there’s a potential structural problem with the Australian government’s support for the status quo. Two especially striking features of the current state of cross-Strait relations are Beijing’s campaign of economic coercion against Taipei and regular People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Air Force flights towards Taiwan. Presumably Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s support for the status quo is not intended to be a statement of support for these economic and military pressure campaigns. But with cross-Strait conditions quickly evolving, the substance of what’s endorsed by support for the status quo is also liable to rapidly change. In other words, with the status quo simply referring to the current state of affairs (something that is near-constantly evolving) the status quo ends up being a rubbery concept. Perhaps it would be preferable then to ditch support for the status quo and replace it with something more specific. For example: “Support for the preservation of peace and security across the Taiwan Strait, including freedom from coercive measures and intimidation.” (Andrew Chubb made a similar point about the imprecision and malleability of status quo language in 2015 in relation to the South China Sea.)

The imperative of clarifying what the Australian government supports in relation to Taiwan is especially pressing as China’s tactics and strategies towards Taiwan continue to evolve. As with the economic coercion and PLA Air Force flights, a notable feature of Beijing’s approach to Taipei is to incrementally increase pressure in a range of domains. On issues like the Taiwanese economy’s participation in regional free trade agreements or the number of countries that diplomatically recognise Taiwan, China is seeking to push the envelope and ensure that the status quo continues to evolve in its favour. This means that ongoing statements of support for the status quo will strengthen China’s position by indirectly legitimating Beijing’s creation of new diplomatic, economic, military, etc., realities.

To be fair, ministers Wong and Marles each made plain that Australia opposes unilateral changes to the status quo. But once these unilateral changes have been made, a new status quo is created. And even if one still opposes those past unilateral changes, expressing support for the status quo can be (mis)interpreted as, by implication, an endorsement of the changes that brought about the new status quo. Given that the Australian government presumably doesn’t seek to legitimise a series of new status quos created by China’s evolving tactics and strategies, there’s a strong case for dispensing with “support for the status quo.” It should be, I think, replaced with language that more precisely signals Australia’s position on the preferred state of cross-Strait relations. Namely, that they be free from coercion and intimidation and be consistent with the preservation of peace and security.

The electoral factor in China’s changed tone

China’s Ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, speaking at the 15th Australia-China Emerging Leaders Summit on 29 July:

“Regrettably, in the past few years, our relationship has encountered serious difficulties. With the new government in office following the Australian federal election this year, our bilateral relations are facing new development opportunities. Recently, high-level bilateral engagements and communication have been conducted, and important consensus has been reached on advancing China-Australia comprehensive strategic partnership and promoting mutually beneficial cooperation. To maintain, consolidate and strengthen this positive momentum, it requires joint efforts from both sides.”

Quick take:

This is another strong statement of optimism from Ambassador Xiao about the prospects for improved Australia-China relations under the Albanese government. But beyond the positive messaging, these comments are also noteworthy for their tinge of partisan politics. Different levels of the Chinese government have long made plain their dissatisfaction with the Morrison government and have recently emphasised Beijing’s openness to a relationship “reset” with the arrival of the Albanese government. But Ambassador Xiao’s comments are unusually direct in attributing the prospect of improved ties to a specific event: the departure of the Morrison government. As well as being an uncommonly clear statement from a foreign government about its preference for a particular Australian government, this comment raises some big analytical questions about what’s driving the recent softening in China’s diplomatic rhetoric.

On one level, the above point might seem entirely elementary. The Chinese government clearly had a dim view of the Morrison government and its key representatives. But on another level, the possibility that the bilateral diplomatic trajectory altered course as a result of a change of government could shape the interpretation of current dynamics in the Australia-China relationship. As I’ve highlighted in recent fortnights, Canberra has softened elements of its messaging about Beijing and this shift has been noticed and presumably welcomed by the Chinese government. One plausible inference from this is that the shift in Australia’s rhetoric has contributed to the recent diplomatic détente between Beijing and Canberra. This explanation attributes an elevated degree of agency to the Australian government and its ability to shift diplomatic dynamics through its choice of rhetoric.

But an alternative explanation suggested by Ambassador Xiao’s recent comment would be that the shift in the diplomatic dynamic has little (if anything) to do with Canberra’s changing language. Extrapolating from the Ambassador’s comments, this shift might have been much more a function of the simple fact that the 21 May federal election ushered in a change of government. On this telling, China gave Australia a diplomatic grace period purely (or at least largely) as a result of the changing of the guard in Canberra. And this might have occurred even if the Albanese government hadn’t in any way softened its rhetoric.

Of course, we’re in the speculative realm of hypotheticals at this point. But it strikes me that it’s a line of analysis worth pursuing: It holds out the prospect of answering the question of whether the Albanese government’s tonal change is producing results. By using softer language, is Australia shaping China’s behaviour and prompting a softer response? Or is it just coincidence that Beijing’s softer messaging coincided with Canberra’s softer messaging (i.e., has the Chinese government actually just been responding to the result of the federal election)?

These questions also matter for figuring out the future trajectory of the relationship. If Canberra’s change in rhetoric has (at least to some extent) prompted Beijing’s change, then there’s a much better chance that the Australian government can shape China’s behaviour via ongoing and additional changes in messaging. But if Beijing is just responding to the end of the Morrison government and the Albanese government’s more cautious language hasn’t had an impact, then there’s less of a reason to think that Canberra will have the power to change the bilateral diplomatic dynamic via its messaging. If the latter is the case, then we’re likely to be in for a reversion of sorts to a rougher ride in the Australia-China relationship, notwithstanding Ministry of Foreign Affairs talk of the prospect of the “steady development of economic and trade ties” (e.g., here and here). If the lack of influence of Canberra’s change in diplomatic tone is right, then Australia may not have effective tools at its disposal to encourage China to offer more diplomatic olive branches. And once it becomes clear to Beijing that the change in government hasn’t ushered in (many or perhaps any) substantive China-related policy shifts from Canberra, the crop of diplomatic olive branches is likely to wither.

Australia’s coal exports keep climbing

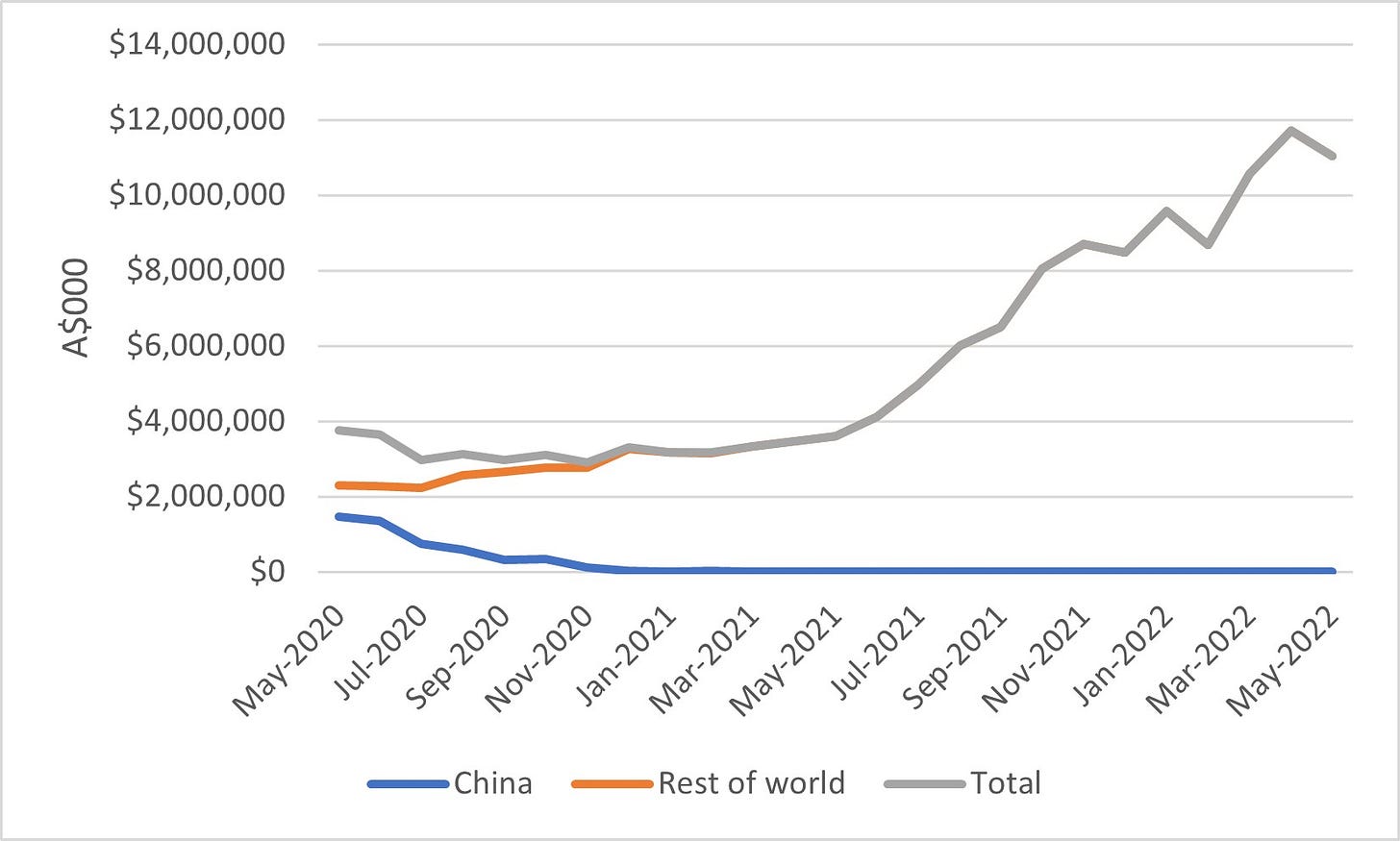

The monthly value of Australia’s coal exports (to China, the rest of the world, and total, May 2020 to May 2022):

Quick take:

Speculation is now swirling about the possibility of China easing its informal restrictions on imports of Australian coal. This promising chatter has even extended to a relatively upbeat assessment of the Australia-China trade relationship in the nationalistic Global Times (hat tip to a reader for directing me to this). But despite those positive atmospherics, the latest Australian trade data from May 2022 still has the total value of Australian coal entering China sitting at $0. Notwithstanding this long-flatlining figure (it hasn’t budged from $0 since March 2021), the monthly value of Australian coal exports to the rest of the world continues to boom. Due in no small part to an astronomical run up in coal prices, the value of this export to alternative markets is now nearly four times the value of Australia’s coal exports to China and the rest of the world combined prior to Beijing introducing its informal trade restrictions on coal in November 2020.

As always, thank you for reading and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections very much appreciated.