China's military modernisation, bilateral bipartisanship, and crustacean exports

Fortnight of 14 to 27 March 2022

Different notes on China’s military modernisation

Minister for Foreign Affairs Marise Payne speaking to the ABC Radio National’s Patricia Karvelas on 24 March:

“I would note that China has increased its defence spending in the region by around seven per cent. They’re entitled to do that. We don’t criticise that. But ultimately what’s essential here is transparency. Transparency is vital. Australia is completely transparent about the approach that we take on defence spending. And, frankly, I’d urge all countries to be that transparent about capabilities and intentions as we are.”

Minister for Defence Peter Dutton addressing the American Chamber of Commerce on 18 March:

“[W]e know that China’s military build-up is of significant concern.

“Nations are, of course, entitled to modernise their military forces consistent with their national interests. We’re in the process of doing that now. But let’s be very frank – China is undertaking the largest peacetime military build-up of modern times.”

…

“Unless China provides more transparency and engages in strategic reassurance measures, regional neighbours like us, like many other countries in the region, cannot help but see this build-up as directed at them.”

Quick take:

Although it’s no surprise that ministers responsible for different portfolios would frame China’s military modernisation differently, the rhetorical contrast is nonetheless striking. One plausible interpretation is that despite the divergence in tone, both ministers are saying substantively the same thing. They are both in essence calling for more transparency regarding military capabilities and strategic intentions. Still, the Minister for Defence’s use of similarly strong language in two other recent speeches (e.g., here and here) and his clear statement that “China’s military build-up is of significant concern” fit awkwardly with the Minister for Foreign Affairs’ more cautious assessment that “[w]e don’t criticise [China’s increasing military spending]”.

If the audience for this messaging includes Beijing, the contrasting language is likely to be especially confusing. From the Chinese government’s perspective, it’d be hard to know whether the Australian government’s problem is with the growth in China’s military spending and capability in general or whether the issue is specifically what Canberra judges to be a lack of transparency and reassurances. If an analyst or policy officer in Beijing read the transcript of the Minister for Foreign Affairs’ remarks, they might conclude the latter. But if they read the Minister for Defence’s speeches, they might assess that Australia believes China’s military modernisation is itself problematic. (Of course, the Minister for Defence also emphasised the case for transparency and reassurances. But his focus on the scale of China’s military modernisation and Australian and regional concerns could give the impression that even additional transparency and reassurances wouldn’t be enough to allay fears.)

Not that it’s necessarily the job of Australian ministers to coordinate their messaging so as to make the lives of foreign officials easier. But the contrasting tone is nevertheless likely to make it that much harder for officials in Beijing to provide their leaders with a crisp and clear account of Canberra’s position on their government’s drive to build a “world-class military”. Beyond Beijing, these differences of tone might also raise questions in other capitals (including those of allies and partners) about the precise nature of Canberra’s core concern with China’s military rise. Am I overreading these ministerial remarks? Quite possibly. But if they prompt questions for Australians, there’s a good chance they’ll do the same for overseas observers.

None of this is to say that different ministers should use precisely the same language, especially considering that ministerial remarks often reflect the equities and views of their respective departments and agencies. It’s also perfectly reasonable and often necessary for ministers to speak to different audiences. Perhaps the Minister for Defence was seeking to impress upon the Australian public the sheer magnitude and historical significance of China’s military modernisation, while the Minister for Foreign Affairs’ intention might have been to deliver a more conciliatory message to China and the region as a whole. Notwithstanding all that, divergent rhetoric on the question of Australia’s concerns about China’s military modernisation is equally liable to lead to confusion in other capitals, including and especially Beijing.

The Chinese Embassy backs bipartisanship

From the Chinese Embassy’s readout of Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong’s 16 March meeting with Ambassador Xiao Qian:

“Shadow Minister Wong expressed welcome to Ambassador Xiao on assuming his post in Australia and set forth Australian Labor Party’s views on relevant issues on Australia-China relations. Shadow Minister Wong hoped that the two sides would enhance engagement and dialogue.”

Quick take:

The readout from this meeting was eerily reminiscent of the language from the meeting between Ambassador Xiao and Minister for Foreign Affairs Payne on 9 March. These Chinese Embassy readouts have the Ambassador reciting substantively the same points. To both the Minister for Foreign Affairs and her shadow counterpart, the Ambassador reportedly expressed hope that “the two sides will work together to review the past and look into the future, adhere to the principle of mutual respect, equality and mutual benefit, and make joint efforts to push forward China-Australia relations along the right track.” The Chinese Embassy is doubling down on its preferred conciliatory language on the Australia-China relationship.

But even more noteworthy was the apparent similarity between Minister Payne’s and Senator Wong’s remarks to Ambassador Xiao. Both of the Chinese Embassy readouts have the Minister and the Senator delivering (nearly word for word) the same message. The only minor differences being Minister Payne apparently adding an affirmation of the “importance of Australia-China relations” and using the words “communication and exchanges” instead of Senator Wong’s “engagement and dialogue”. Needless to say, I’ve gone way too far down into the weeds. But the similarities are striking and particularly intriguing since (so far as I can see) the Chinese Embassy’s versions are the only official readouts available.

It’s unclear precisely what the consistency of messaging means. Have the Minister for Foreign Affairs and her shadow counterpart independently arrived at the same language or coordinated their messages to the new Chinese ambassador? Or perhaps more plausibly, is the Chinese Embassy simply reusing the same boilerplate language in lieu of reporting the substance of meetings? Or is the Chinese Embassy reproducing broadly the same language as a way of highlighting the bipartisan consensus among Australia’s major political parties on the Australia-China relationship? Regardless, it’s unusual to see such furious agreement on bilateral ties. Especially considering that the Government, the Opposition, and the Chinese Embassy don’t tend to agree on all that much at a time of politicised Australia-China relations and intensifying strategic competition.

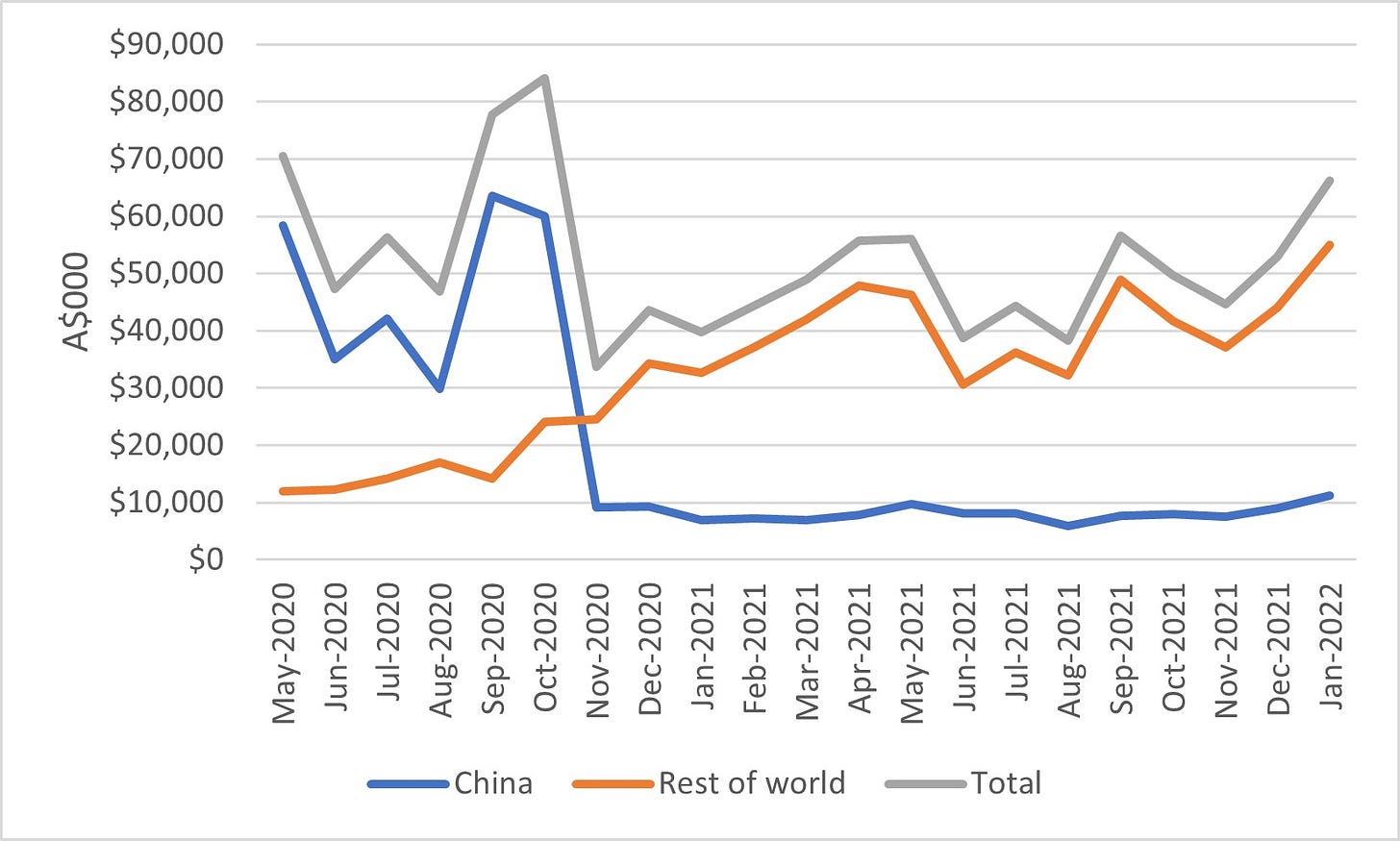

Slowly climbing crustacean exports

The monthly value of Australia’s crustacean exports to China, the rest of the world, and the total value, May 2020 to January 2022:

Quick take:

The redirection of Australian crustacean exports to alternative markets has been much slower than some of the big-ticket energy and resources exports that have been hit by China’s trade restrictions. After the initial collapse in the value of these exports to China in November 2020, their monthly value to the rest of the world only slowly rose and their total monthly value hasn’t yet reached the levels seen immediately prior to the introduction of China’s trade restrictions. Moreover, it’s entirely possible that the above overstates the level of export redirection given that a large portion of Australian crustacean exports go to Hong Kong (circa 30% to 50% by value in recent months) and some of these almost certainly have found (and may still be finding) their way into the Chinese market.

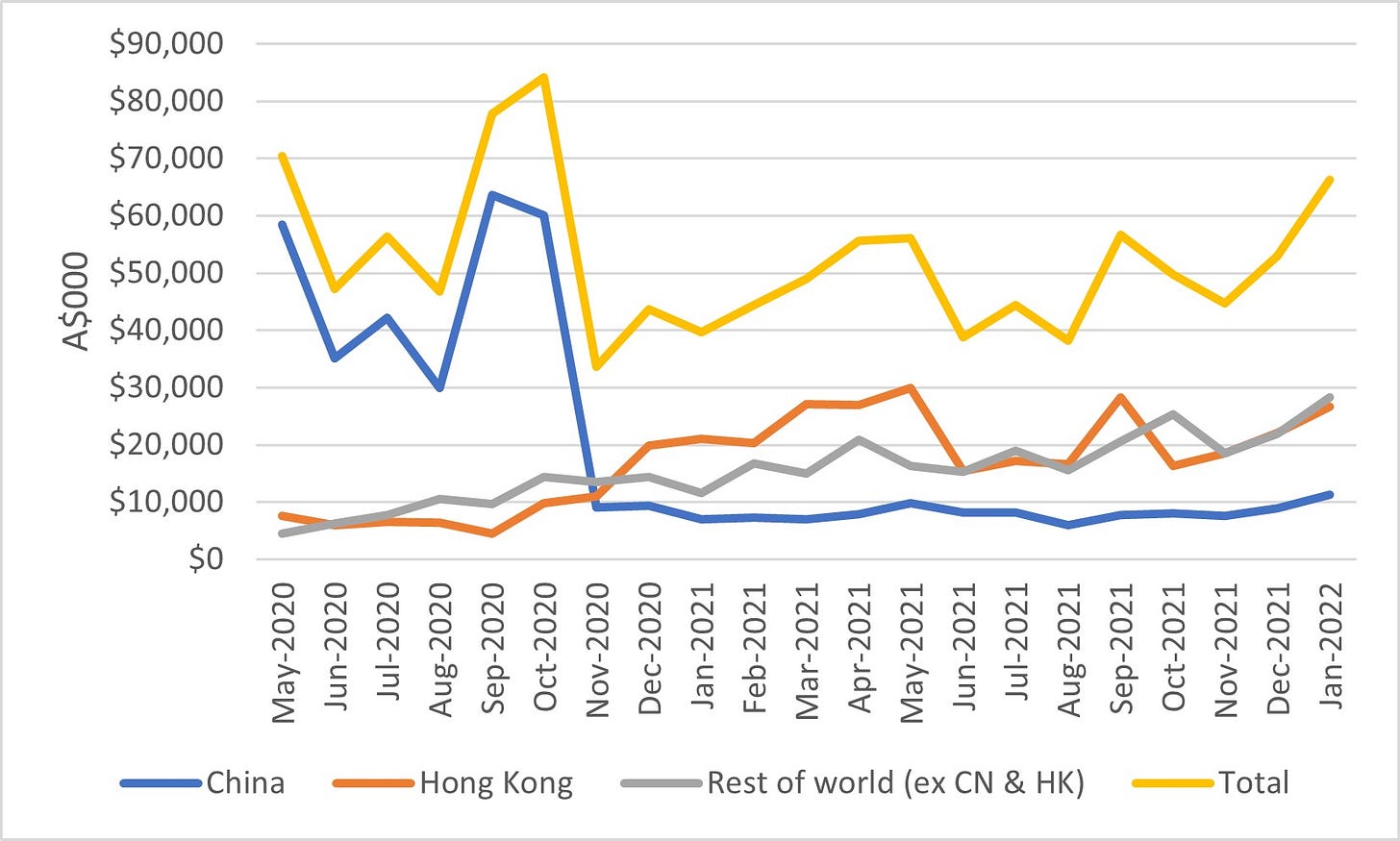

Regardless of whether Hong Kong is a staging point for Australian crustaceans to enter the Chinese market, it’s clear that the city has been a big factor in the redirection of these exports. If one separates Hong Kong from the rest of the world, the rise in the value of crustacean exports to jurisdictions aside from China and the Special Administrative Region looks much more modest (see below). Still, the value of these exports to the rest of the world excluding both China and Hong Kong has gone up circa 60% (admittedly from the base of a low monthly value) since exports to China collapsed in November 2020. As part of the Australian government’s trade diversification agenda, there have also been additional access arrangements for Australian lobster exports (e.g., South Korea in January and Mexico this month). So, there’s a good chance that the value of exports to alternative markets beyond China and Hong Kong will continue to rise, albeit slowly.

The monthly value of Australia’s crustacean exports to China, Hong Kong, the rest of the world, and the total value, May 2020 to January 2022:

As always, thank you for reading and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.