Diplomatic signalling, no negotiating, and export redirection (again)

Fortnight of 14 to 27 February 2022

Whither Australia-China relations?

Chinese Ambassador Xiao Qian speaking in Canberra on 24 February at the presentation of the Gold Great Wall Commemorative Medal in honour of NSW Police Force Senior Constable Kelly Foster:

“Taking the 50th anniversary of the diplomatic relations between our two countries as an opportunity, China is willing to work with Australia to meet each other halfway, review the past and look into the future, adhere to the principle of mutual respect, equality and mutual benefit, and make joint efforts to push forward China-Australia relations along the right track.”

Quick(-ish) take:

This is yet another noteworthy rhetorical olive branch from a Chinese diplomat in Australia. By my rough count, it’s at least the fourth broadly positive speech in just over two months by a senior Chinese diplomat in Australia. This latest example comes off the back of conciliatory speeches in December 2021 and January 2022 by Wang Xining, Chargé d’affaires at the Chinese Embassy in Canberra. Both these earlier speeches emphasised the shared benefits of strong Australia-China ties and expressed cautious optimism about the future of the relationship. Ambassador Xiao’s latest remarks also follow the upbeat message that he delivered on January 26 as he arrived in Australia. (Update: although the speech isn’t yet available in full on the Chinese Embassy’s website, it seems Ambassador Xiao delivered a similarly warm message when he spoke at the Australian National University’s Lunar New Year celebrations on 26 February.)

Although the specifics of Chargé d’affaires Wang’s and Ambassador Xiao’s messaging have differed, there appears to be more consistency in the new ambassador’s language. Both on 26 January and 24 February he emphasised the shared endeavour of jointly pushing “China-Australia relations” either along or back onto “the right track”. Given that we’re talking about just two datapoints in the case of Ambassador Xiao, it’s probably too early to describe this as a concerted messaging strategy from Chinese diplomats in Australia. But at the very least it appears that the new ambassador has some preferred talking points about the bilateral relationship. I’d expect to hear much more about shared efforts to get “China-Australia relations back to the right track” in the coming months, as we did when Ambassador Xiao presented his credentials to the Governor-General earlier this month.

This apparent shift in tone raises the question of what it means for the trajectory of the overall Australia-China relationship. It’s tempting to imagine that these messages could be the prelude to a broader positive shift in bilateral relations, which might eventually take the form of a winding back of trade restrictions and a resumption of ministerial contact. But one swallow does not a summer make. And more importantly, there are bigger weather systems on the horizon suggesting winter will continue. Here are a few of the (many) factors that make me doubtful of a bigger positive shift any time soon:

All four of these speeches included more conciliatory messaging. But that’s hardly surprising considering that they were each focussed on the people-to-people and cultural dimensions of bilateral relations or were delivered on an occasion where a more optimistic tone is de rigueur. Even in the context of a generally frosty bilateral relationship, it’d be highly unorthodox for Ambassador Xiao to let fly with critical invective on either the occasion of his arrival in Australia or a ceremony in honour of Senior Constable Kelly Foster.

The last few weeks of Australian national politics strongly suggest that China policy will feature in the election campaign. With the Coalition seemingly seeking to wedge Labor hard on their tough-on-China credentials, there’s little incentive for the Australian government to respond positively to China’s diplomatic olive branches. In fact, a resuscitation of high-level and public contact between Canberra and Beijing before the federal election might even be seen as a net negative for the Coalition, electorally speaking. Minister for Foreign Affairs Marise Payne seemed on 26 February to be in no hurry to engage with the new ambassador, responding unenthusiastically to a question about a possible meeting: “I will meet the ambassador in due course”.

Perhaps most importantly though, Beijing appears to be asking for Canberra to make changes that any Australian government simply won’t countenance. The bipartisan consensus on China policy that Labor has been at pains to stress of late covers a wide range of political and policy decisions that deeply upset Beijing. These include, among others, Canberra’s foreign investment review policies, often strong public messaging on human rights abuses in China, and support for international maritime law in the South China Sea. Per Ambassador Xiao’s most recent speech, Canberra and Beijing need to “meet each other halfway”. But given such a meeting in the middle is likely to be interpreted in Australia as a call to compromise on non-negotiable political and policy positions, such common ground may remain elusive. (On this, more below.)

Notwithstanding the above, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) press conference on 25 February provided an interesting titbit that may point to a thaw in the Australia-China relationship. Asked about Senior Constable Kelly Foster’s bravery and sacrifice, MFA spokesperson Wang Wenbin responded:

“What has happened is further proof of the unquestionable friendly sentiment between the two peoples. The two peoples’ shared wish is our command. I recall our remarks on the heroic act of Ms. Foster last year: the kindness and compassion of humanity shines brilliantly even in the harshest winter. It is China’s hope that the light will continue to warm the two peoples and nourish the tree of friendship between China and Australia.”

This is remarkably positive—even effusive—language about Australia-China ties. I can’t recall an MFA press conference with language about bilateral relations even remotely this positive in years. (I’d welcome any data points that prove me wrong on that.) This alone doesn’t signify a deeper shift in Beijing’s view of Canberra. As with the caveats listed earlier, you’d expect a story of human fellowship and sacrifice to prompt a relatively positive response from even the most hardened geopolitical strategists. But it’s likely revealing that the Chinese state broadcaster CCTV asked the MFA spokesperson about Senior Constable Kelly Foster and that the story received coverage in Xinhua. Presumably the MFA spokesperson highlighting the commemoration with exceedingly warm rhetoric points to higher-level—though it’s unclear how high— support for emphasising a positive story about the Australia-China relationship. It’s also noteworthy that although both the MFA spokesperson and Chinese press acknowledged Senior Constable Kelly Foster’s bravery and sacrifice at the time of her death in January 2021, no comments were offered about the broader Australia-China relationship at the time.

But I’d still be reluctant to interpret that as being indicative of a broader change in how Beijing sees Canberra. The positive remarks from MFA spokesperson Wang on 25 February came in the midst of the typical tongue lashing given to Australia. That same day Wang responded to a question about Australia’s stance on China-Russia relations during the invasion of Ukraine by saying: “For some time, the Australian side, entrenched in the Cold War mentality and ideological bias, has time and again spread disinformation to smear and criticise China. Such irresponsible behaviour is despicable.” Moreover, despite the recent focus on Russia’s intimidation and invasion of Ukraine, the MFA spokesperson has still had the bandwidth over the last couple of weeks to hit Australia hard with numerous rhetorical broadsides (e.g., here, here, and here).

What do all these diplomatic datapoints mean, cumulatively speaking? My tentative prediction would be that we’re highly unlikely to see a significant improvement in bilateral ties until at the very earliest after the Australian federal election. Even after that, I’d expect any positive changes (if they eventuate at all) to be slow and halting. As well as Canberra’s long-term and bipartisan disinterestedness in compromising on Beijing’s key complaints, macro international factors don’t point to a positive shift in the overall Australia-China relationship. To the extent that bilateral relations are shaped by the tenor of the US-China relationship, global geopolitics, and Beijing’s overarching statecraft, there aren’t any obvious broader changes on the horizon that are likely to have to a significant positive impact on ties between Canberra and Beijing. Relations between Washington and Beijing are likely to remain frosty in the leadup to the US midterms and the 20th Party Congress at the end of this year, while Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is likely to unleash waves of international economic, military, and political instability. Meanwhile, with President Xi Jinping on track to remain in a preeminent position of power in both the Chinese state and communist party after the 20th Party Congress, there’s little reason to expect a major reorientation in China’s external goals and policies. Plus ça change…

Not for negotiating

Prime Minister Scott Morrison speaking to journalists in Adelaide on 25 February:

“[I]n terms of meeting halfway, there are 14 points, I don’t agree with changing any them. So happy to have the dialogue. Happy to have the ministerial and political level dialogue. But those 14 points are not for negotiating.”

Quick take:

It’s not been made explicitly clear whether the Chinese Ambassador’s call for Canberra and Beijing to “meet each other halfway” requires Australia to address China’s now-infamous 14 points. But if it does, any effort to meet halfway will likely be a non-starter. As well bipartisan support for current China policy, the Prime Minister has repeatedly emphasised his commitment to holding the line on the 14 points. As he made plain in an online briefing in early February with members of Australia’s Chinese-languages media: “[T]he only condition on that [dialogue between ministers at a political level] is that we’re not about to go and accede to any of those 14 points, which I suspect you’re all very familiar with. And we think that’s entirely reasonable from our point of view.” So, if there is to be a halfway meeting between Canberra and Beijing, it’ll almost certainly need to be predicated on China’s acceptance that it won’t get any movement on its key complaints. (On the question of what Canberra might be able to do to reengage Beijing at the ministerial level without compromising on policy and political positions, I’ll hopefully share some thoughts about that in the next edition.)

Export redirection (again)

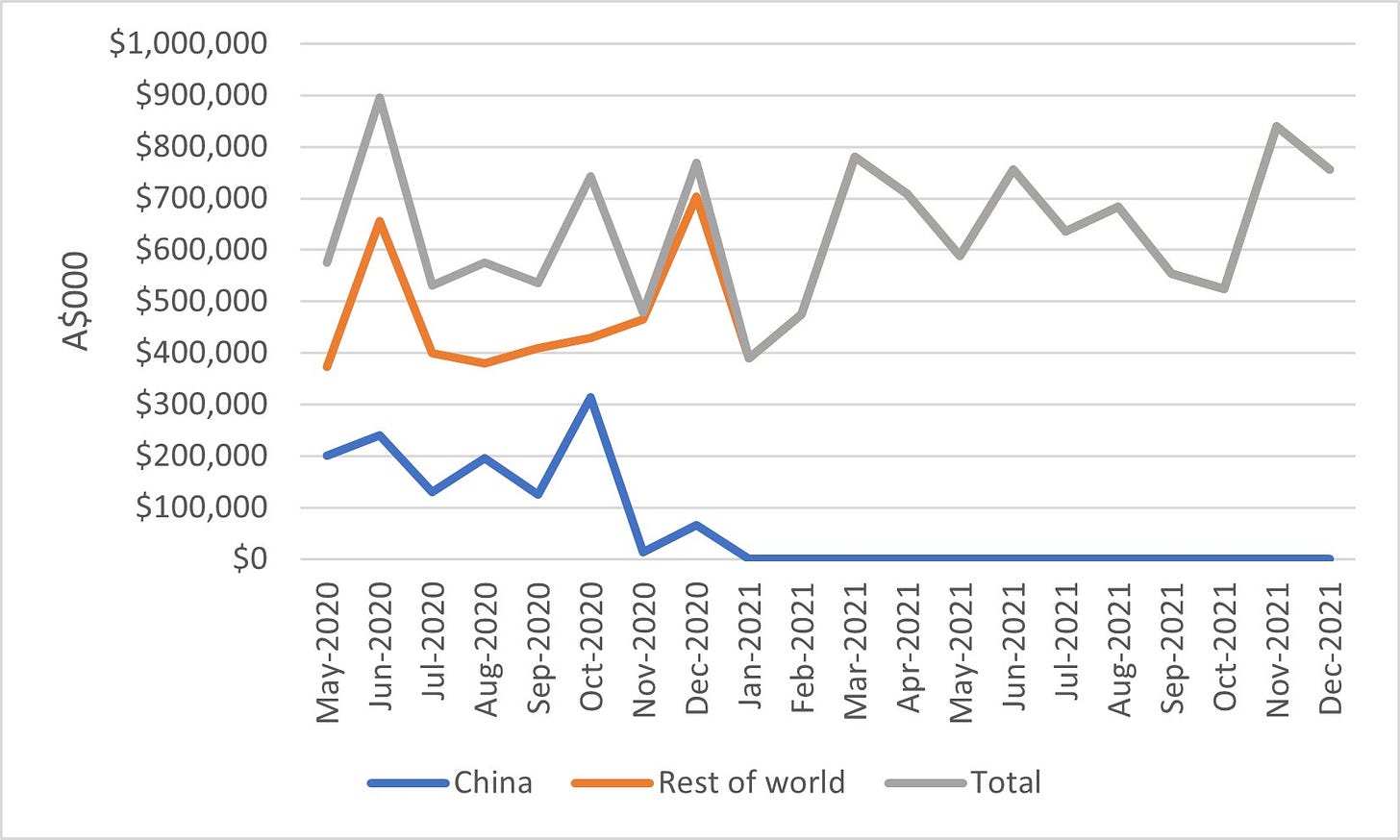

The monthly value of Australia’s barley exports to China, the rest of the world, and the total value, May 2020 to December 2021:

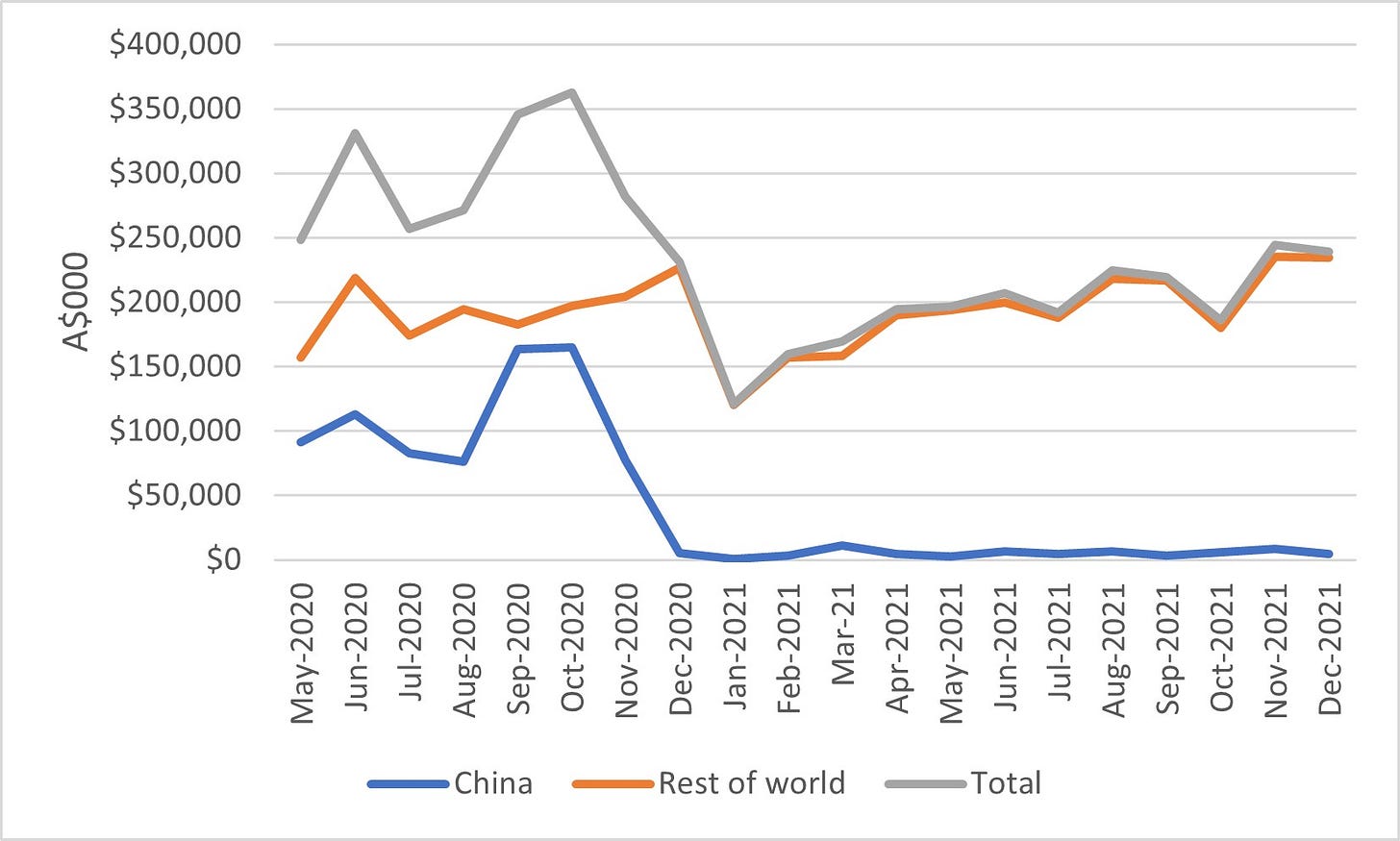

The monthly value of Australia’s copper ores and concentrates exports to China, the rest of the world, and the total value, May 2020 to December 2021:

The monthly value of Australia’s alcoholic beverages (principally wine) exports to China, the rest of the world, and the total value, May 2020 to December 2021:

Quick take:

China introduced trade restrictions against these three exports at different times: barley in May 2020, copper ores and concentrates in November 2020, and alcoholic beverages (principally wine) in November-December 2020. The value of Australian barley and copper ores and concentrates exports to China was flatlining at zero for all of 2021, while the value of alcoholic beverage exports is hovering around roughly 5% of its pre-trade restrictions levels. Despite the sustained collapse of the value of these export to China, monthly trade data up to December 2021 tells a relatively upbeat story about the ability of Australian exporters to redirect to other markets. To varying degrees, the overall value of each of these three exports climbed after low points following China’s introduction of trade restrictions.

But while each of these graphs suggest a positive overall story, they also point to the uneven impact of China’s trade restrictions and the way unrelated factors shape the fortunes of Australia’s exports. Despite Australian barley being priced out of the Chinese market by anti-dumping and countervailing duties, the overall value of Australia’s barley exports has surged, far surpassing its monthly value prior to China’s introduction of trade restrictions. As well as being partially driven by successful redirection to alternative markets, this booming export value is probably primarily a function of favourable weather and global market conditions. Meanwhile, the value of Australia’s exports of cooper ores and concentrates quickly recovered in late 2020 and early 2021, despite being entirely frozen out of the Chinese market. These experiences contrast markedly with the value of Australian wine exports, which have only recovered slowly and are still below their monthly average before China introduced trade restrictions. Among other factors, this is probably a function of the relatively long lead times needed to develop new distribution networks and customers and the associated differentiated nature of wine exports as compared to broadly fungible barley and cooper exports. So, while the overall value of Australian exports impacted by China’s trade restrictions suggests ongoing successful export redirection to alternative markets, adjustments have been (unsurprisingly) much slower and harder for some export industries.

As always, thank you for reading and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

You mis-spell barely and barley :)