Friends like these

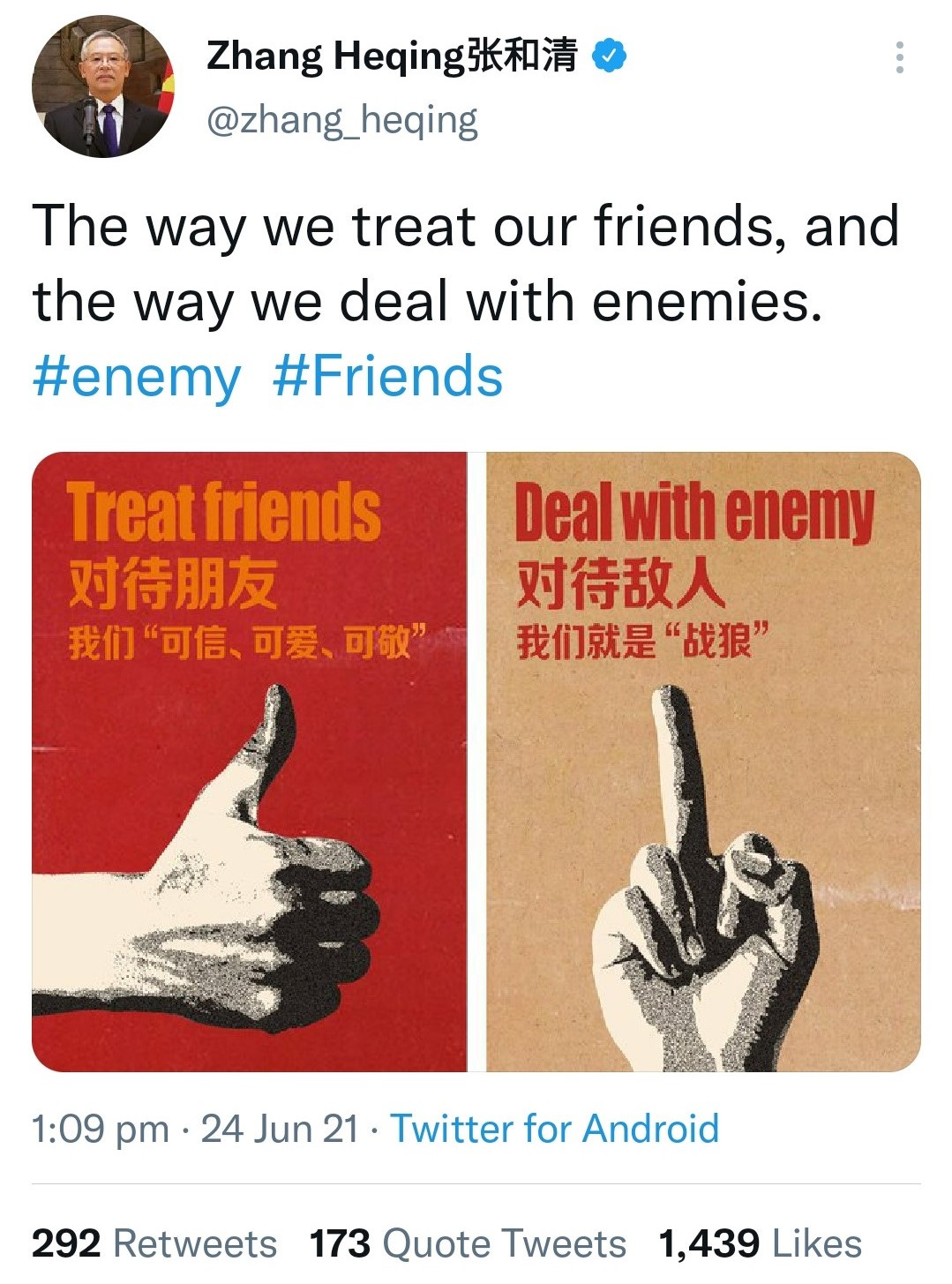

Counsellor Zhang Heqing from the Chinese Embassy in Pakistan:

Quick take:

Zhang’s tweet was soon deleted. So, while the limits of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ (MFA) tolerance for belligerent social media messaging are hard to discern from the outside, it would at least seem that this tweet transgressed the line of what’s considered kosher.

Does this herald a softening of MFA rhetoric in general? Probably not, especially since President Xi Jinping’s recommendation that China’s diplomacy showcase a softer side is aimed specifically at expanding “the circle of friends who understand China.” This would seem to imply that those who persist with their (in the Party-state’s eyes) misapprehension of China will remain outside the friendship circle. And that presumably means that they’ll continue to feel the hard edge of China’s diplomacy as Beijing pushes forward with its “public opinion struggle”.

More generally, both this tweet and President Xi’s recent guidance feel oddly reminiscent of German jurist Carl Schmitt’s definition of politics: “the specific political distinction … is that between friend and enemy.” Or maybe it’s just a doffing of the cap to Mao Zedong’s use of explicit and rhetorically charged friends/enemies distinctions? Either way, this Manichean approach to international politics does not point to a softening of diplomatic rhetoric towards those deemed enemies. And if the MFA press conference on 23 June is anything to go by, there’s little doubt as to which side of the divide Canberra is on.

Adamson’s foreign policy swan song

Recently departed Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), Frances Adamson, addressing the National Press Club on 23 June:

“What we tell the Chinese Government is that we are not interested in promoting containment or regime change.”

“We want to understand and respond carefully – for shared advantage. Not to feed its insecurity or proceed down a spiral of miscalculation.”

“Nor do we see the world through a simplistic lens of zero-sum competition.”

“What we are interested in, and will continue to strive for, is a peaceful, secure region underpinned by a commitment to the rules that have served all of us – China included. An order that will deliver more stability and welfare to its members, as it has done to date.”

Quick take:

This was a weighty address from one of the doyens of Australian foreign policy. There’s a huge amount to unpack in Adamson’s remarks, but two themes from her speech strike me as especially important:

Understanding the aspirations and fears of China’s Party-state will be critical for Australian foreign policy for decades to come. For a range of familiar political, diplomatic, economic, and military reasons, Australia’s strategic choices will play out in a world in which China’s Party-state exerts deepening—and sometimes decisive—influence by nearly every metric. In twenty-first century international politics, China will often be the most significant actor on the world stage. A strong grasp of the Party-state’s worldview and the internal logic of its ideology will be a critical national priority for Australian public servants, political leaders, and commentators. This is not about internalising or acquiescing to Beijing’s views. It’s simply about equipping ourselves to successfully prosecute the Australian national interest in a world in which Beijing’s means increasingly match its ambitions.

I might be overreading Adamson’s remarks, but they sketch a very different image (to my over-sensitive eyes??) than the Prime Minister’s speech earlier this month. The Prime Minister’s talk of liberal democracies “stepping up with coordinated action” sounds more like the ideologically infused language of the Biden administration’s embrace of strategic competition with China. By contrast, Adamson’s focus on a “strategic balance and a regional order based on rules” is much more akin to the pragmatic and paired-back language of the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper (FPWP). Of course, that might just be because of Adamson’s proximity to the 2017 FPWP (she was DFAT Secretary during its drafting and worked closely over many years with a number of the 2017 FPWP’s key authors). But I also wonder whether it speaks to an increasingly important divide in Australian foreign policy between those who support Washington’s goal of maintaining the current US-led and liberal values-infused order and those who see an increasingly values-agnostic balance of power as the unavoidable long-term outcome of US relative decline?

Regardless, Adamson’s last major address as DFAT Secretary deserves to be dissected and debated. Hopefully we’ll still hear from her on China from time to time despite her new role as Governor of South Australia.

Chinese investment stabilises

The latest Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) Annual Report (2019-20) is out. It makes for an interesting read, not least because the total number and cumulative value of FIRB approvals for China only dipped slightly between 2018-19 and 2019-20:

4,314 approvals worth $12.8 billion in 2019-20 Vs 4,901 approvals worth $13.1 billion in 2018-19

Quick take:

Considering that these 2019-20 numbers cover the period of the initial spread of COVID-19 and the economic aftershocks, they seem surprisingly robust. Especially given that China’s Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has dropped off dramatically globally. After reaching a peak of US$216 billion in 2016, Chinese FDI then fell suddenly in 2017 and had nearly halved to US$110 billion in 2020. Despite this international caveat, the trend line of the number of FIRB approvals for China since their peak in 2016 paints a startling picture of decline and points to a much more precipitous fall than the global trends. (It’s not graphed below but looking at the value of FDI over the same period paints a similarly stark picture.)

As always, thank you for reading and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.