Trade talks, a prime ministerial visit to Beijing, and eschewing hard China policy decisions

Fortnight of 30 January to 12 February 2023

Relationship repair continues

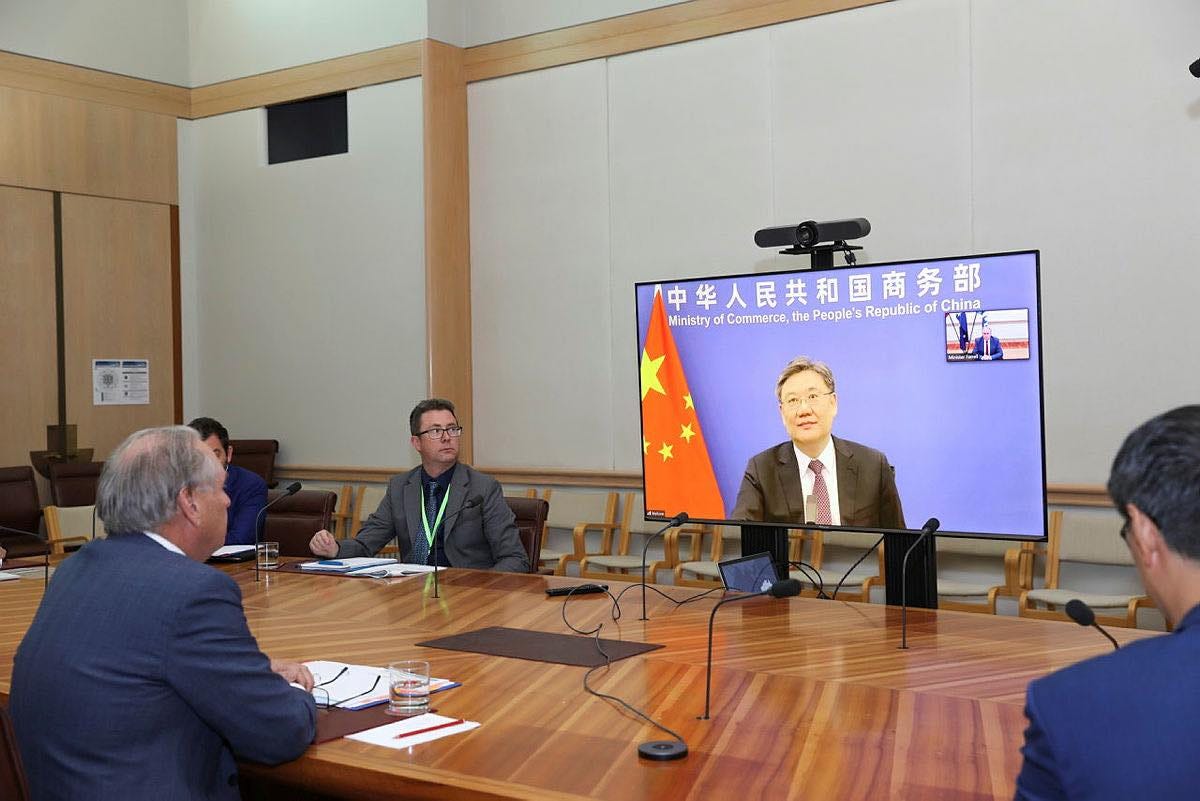

China’s Minister for Commerce, Wang Wentao, making opening remarks during his video call on 6 February with Australia’s Minister for Trade and Tourism, Don Farrell:

“Like you have just said, I’m also looking forward to meeting with you in person at the earliest time. I am also very happy to extend an invitation to you to visit China at a time convenient to you. And I believe that your next trip to China will give you a different impression.”

Quick take:

The warm tone of the publicly released portions of the Farrell-Wang meeting was followed by a series of promising trade signals. Per comments from Minister Farrell to the media on 12 February, there are concrete indicators that coal, rock lobsters, and timber products that were previously blocked from the Chinese market are poised to re-enter. Minister Farrell even said that Australian wine producers “might be expecting some orders in the near future,” notwithstanding China’s anti-dumping and countervailing duties. Then a day later, industry sources and press reporting suggested that trade restrictions on beef would be lifted as well. This doesn’t mean that all the previously restricted Australian exports will necessarily get back into the Chinese market, much less at the same volume and value as before. But it does again point to a progressive unwinding of many (if not all) of China’s trade restrictions in the coming months.

The Farrell-Wang meeting is also yet another indicator that high-level diplomatic ties are in the process of normalising. (I say process because a few ministerial meetings don’t a diplomatic normalisation make.) Unsurprisingly, Minister Farrell has accepted Minister Wang’s invitation to visit Beijing in the “near future,” and both ministers agreed to “enhance dialogue at all levels, including between officials.” Minister Farrell’s impending in-person meeting with Minister Wang will be the twelfth meeting at the ministerial-level or above since the Albanese government came to power in May 2022 and the first time an Australian trade minister has visited China since Senator Simon Birmingham’s Shanghai trip in November 2019.

Despite all these indicators of ongoing relationship repair on both the diplomatic and trade fronts, the Chinese government is still sending out some concerned signals. Following the news that surveillance equipment and intercoms manufactured by Chinese companies would be removed from a range of Australian government buildings, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) reiterated the Chinese government’s concerns about Australia remaining welcoming towards Chinese companies. On 9 February, MFA Spokesperson Mao Ning said: “We hope the Australian side will provide a fair, just and non-discriminatory environment for the normal operation of Chinese companies and do more things that could contribute to mutual trust and cooperation between our two countries.” These talking points were then republished on the website of the Chinese Embassy in Canberra, suggesting that it’s a message Beijing is especially keen for Canberra to hear.

Given the baseline of MFA invective about Australia these past few years, these words were pretty measured. But as I’ve pointed out previously (e.g., here), it is noteworthy that concerns about the environment for Chinese businesses in Australia are still openly raised despite China dramatically dialling down its public criticisms of Australia overall. These concerns are especially conspicuous given that they also featured in the Chinese government’s readout of the Farrell-Wang meeting (available in English and Chinese). Despite the meeting’s generally soft tone, there was at least one pointed message: “China is highly concerned about Australia’s tightened security review of Chinese companies’ investment and operations in Australia and hopes it will properly handle related cases and provide Chinese firms with a fair, open and non-discriminatory business environment.”

The impact on bilateral ties of China’s enduring concerns about the environment in Australia for Chinese businesses remains unclear. But at the very least, it seems that Beijing will be scrutinising intently any cases where it looks like the Albanese government might be edging towards rejecting a large Chinese investment or substantially curtailing the activities of Chinese businesses. Perhaps such a development would be enough to stall or even reverse incremental relationship repair. Meanwhile, it’s hard to imagine that Prime Minister Albanese and his ministers won’t be weighing the possible impact on bilateral ties when mulling over whether to reject Chinese investments or restrict the operations of Chinese businesses. These kinds of decisions may yet prove to be the pointiest bilateral developments of 2023.

Is it possible that concerned messaging about the environment in Australia for Chinese businesses mostly relates to the recent story of the removal of Chinese-manufactured equipment from a range of Australian government buildings? Perhaps. But I suspect Beijing’s concerns are broader. For one thing, these concerns were raised long before this most recent case, including in the wake of the leader-level meetings in November last year. And China has for years strongly objected to the treatment of Chinese investments. Moreover, the decision to remove Chinese-manufactured surveillance equipment and intercoms was limited to a relatively small number of government buildings (at least small in the context of the Australian market overall). My impression is that China is much less concerned about targeted restrictions like that or, for example, not allowing TikTok on government phones. Instead, I suspect that Beijing is much more worried about decisions like knocking back a substantial Chinese investment or excluding Chinese companies from the consumer market more broadly. Given the ban on TikTok in India, a possible ejection from the US market, and murmurings along those lines in some quarters in Australia, China is likely to be concerned about much more dramatic and far-reaching developments than the removal of some Chinese-manufactured surveillance equipment and intercoms from government buildings.

Is Albanese off to Beijing in October?

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese speaking to the Guardian Australia’s Katherine Murphy on 4 February:

Murphy: … Will you either go to Washington or Beijing this year, do you think?

Albanese: I fully expect to. Well, I will be going to the United States this year.

Murphy: Interesting, okay. And Beijing?

Albanese: I don’t have a scheduled meeting there.

Quick take:

Assuming the progressive dismantling of China’s trade restrictions continues, one of the major milestones of relationship repair to follow (though not necessarily the first one) would be a leader-level meeting in either Canberra or Beijing. With Prime Minister Albanese having met Premier Li Keqiang and President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of multilateral meetings in November last year, questions are now being asked about the prospects of such a full-blown bilateral visit. Given Prime Minister Albanese’s much more regular international travel and the relative historical rarity Chinese leaders visiting Australia (by my count, it’s only happened twice in the last 15 years), it seems that a bilateral visit is much more likely to involve Prime Minister Albanese going Beijing. I’m certainly not the first to flag this timeline, but I wouldn’t at all be surprised if Prime Minister Albanese heads to Beijing in October/November this year.

Although these factors are hardly definitive, together they make an October/November visit to Beijing appealing for both the Australian and Chinese governments:

As with Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong’s visit to Beijing in December 2022 to (among many other agenda items) mark 50 years since the establishment of official ties between Australia and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), an October/November visit would be heavy with symbolism. It would coincide with the 50th anniversary of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s trip to Beijing and the first ever trip to the PRC by an Australian Prime Minister. (For those interested in historical vignettes, Prime Minister Whitlam wasn’t the first Australian leader to visit China, depending on how one interprets that contested name. I only recently came across these fascinating records [here and here] of Prime Minister Harold Holt’s visit to Taiwan in 1967.) Historical factoids aside, the anniversary of the first prime ministerial visit to the PRC is an important milestone in the history of Australian foreign policy irrespective of one’s political orientation. But it’s presumably especially significant for the Albanese government given Prime Minister Whitlam’s elevated status in the pantheon of Australian Labor leaders. So, in the wake of speeches and statements lionising Prime Minister Whitlam’s “bold decision” to establish official ties between Australia and the PRC, it’d be unsurprising if Prime Minister Albanese wanted to claim the mantle of “Gough’s legacy” with a trip to Beijing.

Beyond the formal anniversary, Prime Minister Whitlam’s foreign policy legacy also appears to have a deeper resonance for the Albanese government. Although the specifics are obviously vastly different, the broad contours of the Albanese government’s diplomatic positioning have echoes of Whitlam. Prime Minister Albanese, like Whitlam, has sought to prioritise regional engagement and closer ties with Australia’s partners in the Pacific and Asia. Of course, this parallel can only be pushed so far given colossal datapoints like the Albanese government’s embrace of AUKUS (certainly not something that recalls Whitlamesque foreign policy). But I was nevertheless recently struck by the similarities between some of the sentiments expressed by Whitlam while in Beijing in 1973 and Albanese government ministers today: “Australia is moving in a new direction, in its relationships with the world and specifically with the region in which Australia inevitably belongs.” Those much better versed in the history of Labor foreign policy can school me on this, but I don’t think I’m mistaken in sensing a concerted Albanese government effort to draw parallels between their efforts today and elements of Prime Minister Whitlam’s foreign policy posture. Following Prime Minister Whitlam’s footsteps exactly 50 years later would likely help Prime Minister Albanese advance that agenda.

Beyond historical legacies, a visit to Beijing would also likely serve the Albanese government’s retail political priorities. Per recent partisan politicking about Australia-China ties, Prime Minister Albanese seems invested in relationship repair as one of the signature achievements of his first term. He has criticised the previous Coalition government for the breakdown of communication with China and explicitly presented himself as the leader who was able to reengage with Beijing. To be sure, Prime Minister Albanese has been exceedingly loose with the historical record in claiming that the previous “government … chose to not have a single conversation with China” and that there was “no talk” between Canberra and Beijing in the last term of government (e.g., here and here). These falsehoods aside, few moves would more powerfully play into Prime Minister Albanese’s narrative of being the leader who repaired the Australia-China relationship than being the first Australian prime minister to visit China since Malcolm Turnbull made the trip in 2016.

Assuming that relationship repair hasn’t been derailed by a dramatic uptick in tensions between Canberra and Beijing, the Chinese government is also likely to welcome a visit by Prime Minister Albanese in October/November. Per the (I think) pointed detail in Minister for Foreign Affairs Wong’s press release about the December 2022 visit, the meeting occurred “at the invitation of” China, suggesting that Beijing did the asking. And the Chinese government certainly feted the trip and the 50th anniversary of official relations with what looked like a hefty dose of pomp and circumstance. I wouldn’t be surprised if the Chinese government also wanted to mark the 50th anniversary of Prime Minister Whitlam’s visit with some pageantry. And what better way to do that than with a visit by Prime Minister Albanese himself?

Of course, none of this means that a prime ministerial visit to Beijing will necessarily take place in October/November. If bilateral ties continue on their upward trajectory, Prime Minister Albanese might be packing his bags for Beijing in just a couple of months once General Secretary Xi locks in another five years as president. Or he might never make the trip if the relationship tanks again thanks to any number of permutations. Maybe news will break that the Foreign Investment Review Board has rejected a large Chinese investment just as a People’s Liberation Army Air Force J-16 accidentally collides with an Australian P-8 in the South China Sea? Still, leaving aside severe turbulence in the Australia-China relationship, a range of factors make an October/November trip to Beijing plausible. Perhaps even with Western Australian rock lobsters on the banquet menu and toasts with a Barossa shiraz. OK, maybe I’ve now transitioned from the plausibly speculative to the purely fanciful.

The possible policy implications of relationship repair and a Beijing visit

Prime Minister Albanese speaking to journalists on 11 January:

“No one can argue that the the [sic] mood in the relationship has not been enhanced substantially since I’ve been Prime Minister. I’ve been busy making sure that that occurs.”

Quick take:

Assuming that the above analysis/speculation is roughly right (as ever, no guarantees), what might be the policy implications of ongoing relationship repair and a Beijing visit? One possibility is that the prospect of ever-improving ties and a trip to Beijing will make it more likely that the Albanese government will hold back from making tough China policy decisions. Given China’s track record of punishing Australia with diplomatic freezes and trade restrictions in response to actions that Beijing judges are adversarial to its interests, Canberra may make the tactical choice of stalling or not taking decisions that are liable to upset the Chinese government.

This might mean slow rolling the review of the 99-year lease of Darwin Port to the Chinese company Landbridge Group or finding that the lease can remain, despite Prime Minister Albanese’s previously strong opposition. It might mean holding off on sanctions against Chinese officials implicated in severe human rights abuses in Xinjiang, despite Minister for Foreign Affairs Wong’s cautious support for such sanctions in the past. Or it might mean delaying decisions on contentious foreign investments from Chinese companies. (Addendum: The Albanese government’s provisional decision on 14 February to not veto Confucius Institutes and instead place them under ongoing review seems to fit this pattern of calibrating China policy decisions to maintain a relatively strong security posture while also, crucially, seeking to not aggravate Beijing.)

This is an admittedly more speculative point, but it’s also entirely possible that the prospect of these kinds of more cautious choices from Canberra was part of Beijing’s calculus when it decided to pursue relationship repair. The Chinese government may have understood that reengaging with Australia at the political level and progressively removing trade restrictions would encourage the Australian government to not take what China considers to be adversarial positions. In addition to the economic and other grounds that China might have had for progressively normalising ties with Australia, Beijing may have also assessed that bilateral relationship repair would reduce Canberra’s appetite for risk on policy questions deemed highly sensitive by the Chinese government, including its human rights record and the Australian investment environment for Chinese businesses. In other words, by turning the diplomatic and trade taps back on, Beijing may have sought to incentivise Canberra to take China policy decisions more conducive to the Chinese government’s interests.

Of course, the prospect of a progressive normalisation of high-level diplomatic ties and the removal of trade restrictions doesn’t necessarily mean that the Australian government will avoid tough China policy decisions in 2023. And if my analysis last edition is broadly correct, then Australia might actually have much more leeway to take hard-edged China policy decisions. With China inviting Australian minsters to visit and unilaterally dismantling trade restrictions (seemingly) without winning any concessions from Canberra, Beijing looks especially eager to repair the relationship. So much so that perhaps Australia could actually push the envelope on tough China policy decisions without jeopardising relationship repair. Maybe China is so keen to repair the Australia-China relationship that it wouldn’t once again freeze out Australian ministers and exports even if Canberra, for example, imposed targeted sanctions on Chinese officials implicated in severe human rights abuses in Xinjiang?

Yet one could just as easily draw the opposite conclusion. Sure, Beijing appears to want relationship repair without Australia having reversed course on its past decisions. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that China would be willing to continue down the path of improving ties irrespective of what Australia does now. Perhaps China can live with the Australian bipartisan consensus on what it considers to be a range of past adversarial decisions. But that’s not the same as being willing to let relationship repair continue apace if Canberra takes tough China policy decisions in the future. Moreover, it’s entirely possible that Beijing is allowing relationship repair to occur now because Canberra has already held off on some tough China policy decisions. There’s no evidence (at least that I’m aware of) to suggest an explicit quid pro quo between Canberra and Beijing whereby the Australian government doesn’t take tough China policy decisions in exchange for relationship repair. But with Canberra, for example, deciding to not impose targeted sanctions (at least for now), Beijing probably likes what it sees and therefore may feel vindicated in its decision to repair the relationship.

So, what are we likely to see from Australia’s China policy in the coming months? Will Canberra hold back on tough China policy decisions for fear of upsetting Beijing and jeopardising relationship repair and a mooted China visit? Or does Beijing’s apparent keenness to progressively normalise ties without winning any policy reversals from Canberra suggest that the Australian government will be able to simultaneously take tough China policy decisions while rehabilitating both diplomatic and trade ties and scoring a leader-level invitation? For now, I can’t confidently bet either way. But if I was pressed, I’d say that Prime Minister Albanese’s political investment in relationship repair points to an aversion to tough China policy decisions from Canberra for most of 2023.

Addendum: Fear of upsetting the Chinese government and thereby jeopardising relationship repair and a potential invitation to Beijing are, of course, not the only reasons that Canberra might avoid tough China policy decisions. For example, the decision to not veto Confucius Institutes could well have been driven as much by concerns about the potential overreach of government power (and other considerations) as the likely negative reaction from China. Similarly, the Albanese government might have so far not sanctioned Chinese officials primarily because of doubts about the ability of such tools to improve human rights conditions on the ground. Regardless of these and other factors at play, Beijing’s track record of punishing Australia for perceived infractions means that Australian officials and ministers are presumably also considering potential retribution from the Chinese government when deciding whether to pull the trigger on tough China policy decisions.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

The following accords (somewhat):

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1xwIYpBBblnF_4voYfodPK-6te3Dc_BHtaA1Zlq0ZnAY/edit?usp=sharing

With China inviting Australian minsters to visit and unilaterally dismantling trade restrictions (seemingly) without winning any concessions from Canberra, Beijing looks especially eager to repair the relationship?

It's called "loosening and tightening the reins”. Deng loosened them, Xi tightened them.

If Australia doesn't get the message (and I believe the US will not permit it to), then Australia will remain in the sin bin, which suits Washington fine.