Leader-level meetings and did China just drop its expectations of Australia?

Fortnight of 31 October to 13-ish November 2022

Although Tuesday’s leader-level meeting falls outside the fortnight that I would have normally covered in this edition of the newsletter, I hope you’ll forgive me for being a bit flexible with the date range. Starting with that meeting, this edition is an extended analysis of what the restart in high-level contact and associated messaging might tell us about China’s strategy towards Australia. Next edition will revert to the regular programming of canvasing a broader suite of bilateral issues.

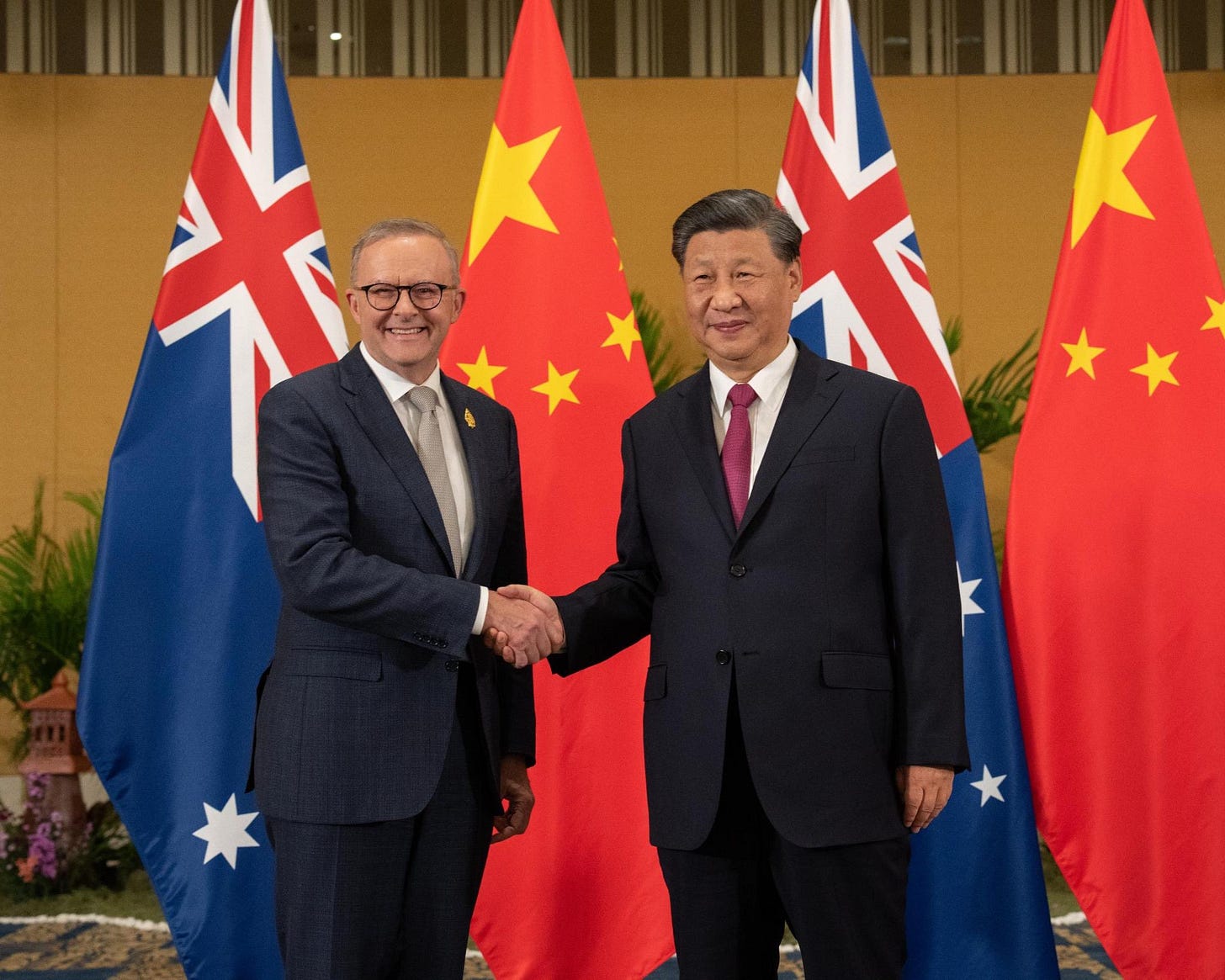

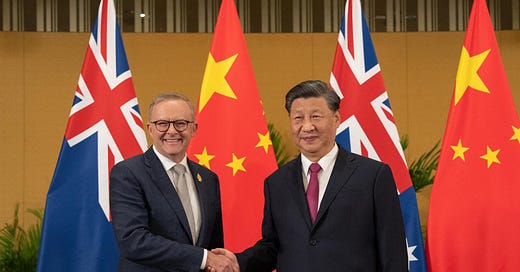

When Albanese met Xi (and Li)

From China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ (MFA) readout of the meeting between Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and President Xi Jinping on 15 November:

“A mature and stable bilateral relationship should first and foremost be reflected in putting the differences and disagreements between the two countries in the right perspective. It is imperative to rise above disagreements, respect each other and seek mutual benefit and win-win results, which holds the key to the steady growth of the relationship.”

Quick take:

Consistent with predictions made tentatively in May and more confidently in September in this newsletter, there’s finally been a long-awaited leader-level meeting between Australia and China. To be precise, there have been two such meetings in the space of just a few days. On 12 November, Prime Minister Albanese met briefly with Premier Li Keqiang on the sidelines of the East Asia Summit (EAS) in Phnom Penh (MFA readouts in English and Mandarin). This was quickly followed by the longer formal meeting with President Xi three days later on the sidelines of the G20 in Bali (Mandarin version of the MFA readout here).

As I wrote for The Age on Wednesday, the simple fact that these meetings occurred at all is a massive milestone for Australia-China relations. Understandably, much of the questioning from journalists after the Albanese-Xi meeting centred on the next steps for bilateral ties. Will China’s trade restrictions be slowly unwound? And is Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong now planning a trip to Beijing? Although these are critical questions for Australia, the publicly available information doesn’t give much away on either of these points. However, for what it’s worth, I wouldn’t at all be surprised if we had answers in the affirmative to both of these questions in the coming months.

But before we delve into what these meetings might mean for the future trajectory of the Australia-China relationship, it’s worth pausing briefly to consider their historical significance. This is the first time that an Australian prime minister has met face-to-face with China’s President Xi since the brief conversation between Scott Morrison and the Chinese leader in June 2019 on the sidelines of the G20 in Osaka. (And the break in contact with President Xi goes as far back as 2016 if one only counts more formal bilateral meetings.) Meanwhile, it’s the first prime ministerial meeting with Premier Li since the 7th Annual Leaders’ Meeting in November 2019 on the sidelines of the EAS in Bangkok. These meetings bring to an end the longest gap in leader-level engagement since the break in such contact following the Tiananmen Square massacre in June 1989.

Whither China’s expectations of Australia?

From the Chinese MFA readout of Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s 8 November phone call with Minister for Foreign Affairs Wong:

“[T]he two sides need to gradually address respective legitimate concerns, and work jointly to make positive contributions to tackling current global challenges.”

Quick take:

Like Prime Minister Albanese’s recent meetings with Chinese leaders, this readout (in Mandarin here) is striking for how much it downplays China’s expectations of Australia. In the two previous in-person engagements between ministers Wong and Wang in July and September, the MFA readouts made plain that Beijing expected Canberra to take significant remedial action to get the relationship “back on the right track.” The Chinese government might have started sending out more positive messages in late 2021 and ramped up the warm(er) outreach after the Australian federal election in May 2022. But Beijing never resiled from a long, albeit ambiguously couched, list of expectations.

The MFA readout of Minister for Foreign Affairs Wong’s first meeting with Foreign Minister Wang in July provided a four-point list of things that China expected from Australia. These included “regarding China as a partner rather than a rival” and “building positive and pragmatic social foundations and public support.” Then in a major address at the National Press Club in August, China’s Ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, spoke more voluminously about these points with a list of five similar expectations. In the second foreign minister’s meeting in September, Foreign Minister Wang made the case for “uphold[ing] a more positive mindset, send[ing] more positive signals, [and] tell[ing] more stories of win-win cooperation.” In recent months, MFA spokespeople have similarly stressed a range of actions that Australia should be taking to improve the bilateral relationship. Recent leader- and ministerial-level engagements are striking for their deemphasis of these long-expressed Chinese government expectations of Australia.

To be sure, some of the exhortations in the recent Wong-Wang discussion could still be interpretated as vague and general references to these past Chinese government expectations. These include calls to “seek common ground while shelving differences,” “strive for mutual benefit and win-win results,” and “gradually address respective legitimate concerns” But even if these are still oblique references to China’s expectations, the increasingly vague expression of them is itself a noteworthy shift in the Chinese government’s messaging. More importantly, this recent and vaguer expression of expectations is also much more reciprocal (i.e., what Beijing and Canberra should do together rather than what Australia alone should do).

This increasingly vague and reciprocal expression of expectations is consistent with the readouts of Prime Minister Albanese’s meetings with Premier Li and President Xi. The readout from the Albanese-Li meeting only flagged general expectations in the form of reciprocal actions and noted that “China is … ready to meet Australia halfway.” Meanwhile, the readout from the Albanese-Xi meeting further downplayed any specific expectations, stating that: “The two sides need to take stock of experience and lessons, explore ways to steer the relationship back onto the right track, and move it forward in a sustainable manner.” Exploring options to improve the relationship presumably implies that Australia should consider what changes it should make. But even so, this is much softer and more reciprocal an expression of expectations than in past months.

Of course, China’s decision to not clearly and publicly articulate expectations of Australia doesn’t necessarily mean that Beijing doesn’t harbour them. Absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence. Moreover, China’s public deemphasis of such expectations could also be explained by circumstantial factors. For one thing, it may not have been feasible for Premier Li to list all of China’s expectations to Prime Minster Albanese in the few minutes they reportedly spent chatting. And Beijing might have decided for tactical reasons to not weigh down the mood of the first meeting between President Xi and an Australian prime minister in years by (re)enumerating all the things that it thinks Canberra is doing wrong. It’s also entirely possible that a full account of China’s expectations wasn’t publicly flagged after the Wong-Wang ministerial call because of its timing in the lead up to the Albanese-Xi meeting. Finally, it’s equally plausible that the Chinese government judged that regardless of what was said privately in all these engagements, it was simply best to not detail any expectations of Australia in publicly available readouts.

All these possible permutations notwithstanding, it’s at least clear that China is dialling down the public expression of its expectations of Australia. Does that mean these expectations have disappeared and that the Australia-China diplomatic and trade relationships will normalise without Beijing waiting for substantive policy compromises from Canberra? It’s far too early to say. But the deemphasis of previously publicly expressed expectations does raise the tantalising prospect that the Chinese government has blinked. Perhaps it has abandoned the public expression of such expectations because it wants to slowly and quietly back out of a situation in which the normalisation of elements of the bilateral relationship was dependent on the Australian government making substantive policy compromises that Canberra wasn’t going to make?

This interpretation is all the more plausible considering that the recent ministerial- and leader-level meetings are precisely the kinds of engagements that China apparently previously said could only occur if Australia made amends. In other words, Beijing is not publicly proffering its expectations of Canberra in precisely the kinds of bilateral engagements that China had previously said (albeit to the previous Australian government) would only restart if Australia met certain conditions. By this account, Beijing has blinked twice. First, China is offering up (without its expectations having been met) the kinds of engagements that were seemingly previously contingent on Canberra doing what Beijing wanted. And second, in recent high-level meetings, China has (seemingly) not expressed strong and clear expectations for further relationship repair.

Are alternative explanations possible? Absolutely (on which, more below). And am I overanalysing these recent ministerial- and leader-level readouts? Certainly possible. But the combination of Beijing tamping down its public expectations of Canberra combined with recent leader-level engagements is prima facie grounds for thinking that the Chinese government is in the midst of a consequential walk back of its strongarm efforts to push the Australian government to make substantive policy compromises.

What might explain China’s (apparent) walk back?

Ambassador Xiao speaking in Sydney on 5 November:

“Since the new Australian Government came to power this May, a possible opportunity to reset the China-Australia relations has emerged. Leaders of our two countries made effected communication and contacting, resulting in important consensus. This created a good opening for the well developing of mutual relations in the future. We hope that both sides can take concrete actions and work in the same direction based on the principle of mutual respect and mutual benefit to bring China-Australia relations back on the right track in near future.”

Quick take:

Considering the wide range of severe substantive policy disputes between the Chinese and Australian governments, the public deemphasis of China’s expectations combined with the resumption of leader-level engagement is puzzling. It’s especially odd considering that the areas of disagreement between Australia and China have arguably expanded and intensified this year. On issues like China’s security role in the Pacific and military intimidation of Taiwan, Canberra and Beijing have found themselves even more firmly at loggerheads. So, what explains Beijing’s about-face despite Canberra not having compromised on substantive policy points?

Although the following by no means exhaust all the possible explanations, there are five plausible reasons that China might be publicly downplaying its expectations of Australia:

Beijing has been (to some degree) mollified by Canberra’s abandonment of especially strident rhetoric on China, meaning that substantive policy compromises are no longer such a strong expectation for improvements in bilateral ties.

Beijing held the previous Morrison government and some of its ministers in especially low esteem, which meant that the simple fact of a shift to the Albanese government was enough of a reason for China to allow its relationship with Australia to slowly improve without its expectations being met.

Beijing has (accurately) determined that Canberra ultimately won’t meet its expectations and so has decided to allow the relationship to recover (somewhat) without any substantive policy compromises from Canberra.

Beijing’s public deemphasising of its expectations is a temporary tactical manoeuvre aimed at fostering some goodwill in Canberra. Although these expectations are dormant for now, they aren’t gone and will again be expressed publicly.

Beijing judges that regardless of its expectations, keeping the Australia-China relationship in the freezer is now counterproductive to its interests. This might be especially so given that Beijing’s previous approach likely contributed to hardening views on a range of China-related policy questions in Canberra and encouraged even deeper engagement between the Australian government and broadly likeminded democracies, including the United States, Japan, and India.

These explanations are not mutually exclusive. For example, Beijing being somewhat placated by more conciliary diplomatic rhetoric on China from the Albanese government is perfectly consistent with the Chinese government being relieved that the Morrison government is no longer in power. It’s also entirely possible that all the above points are correct, and ultimately, it’s their combination that explains why China has decided to publicly downplay its expectations.

That said, some of these explanations are by their nature harder to prove and more speculative. Reasons 3-5 especially fall into this category given that these reasons rest on either predictions about the future or assessments of the Chinese government’s private positions and confidential strategies. By contrast, there’s evidence in the public arena providing some (albeit not definitive) justifications for reasons 1 and 2. It seems clear, for example, that Beijing harboured enmity towards elements of the Morrison government, welcomed the change in government in May, and appreciated some of the Albanese government’s shift in tone and style. Overall, we can probably be moderately confident that 1 and 2 are correct, while 3-5 are plausible but hard/impossible to confirm.

Regardless of their accuracy, all the above explanations should probably be treated as fairly low-confidence accounts of why China might be publicly downplaying its expectations of Australia. And it’s possible that something else entirely has motivated China’s (seemingly) shifting approach to Australia. But despite all the uncertainty surrounding the best explanation(s) for Beijing’s (apparently) changing stance, the question of what is motivating China can’t be ignored. The answer to this question will shape:

analysis of not just the Australia-China relationship, but also China’s statecraft more broadly;

our understanding of the next steps in the evolution of the Australia-China relationship; and

the lessons that should be derived for not just the Albanese government, but also other governments that are now or might soon be forced to manage fraught ties with China.

If, for example, one accepts explanation 3 above (that Beijing is relenting because Canberra didn’t compromise), then one might derive the lesson that neither Australia nor other countries should compromise in the face of China’s threats or moves to deny them high-level diplomatic access. On this reading, holding the line on all substantive areas of China-related policy allowed Australia to demonstrate that threats and pressure weren’t going to get the Chinese government its desired result. By contrast, if one accepts 1 (that Canberra’s softer diplomatic rhetoric induced change in Beijing’s approach), then one might derive the lesson that deft and sometimes less direct diplomacy is the best way to manage China. Regardless of the breadth and depth of Australia’s disputes with China, Canberra was able to calibrate its language to manage Beijing’s sensitivities and other capitals can potentially do the same.

Given all the uncertainty surrounding the best explanation(s) for why China might be publicly downplaying its expectations, I won’t presume to derive hard and fast policy lessons from this episode. But there is perhaps a relevant epistemological point that bears emphasising: multiple plausible explanations exist for China’s (apparent) change in approach. Although (as I note above) there’s probably a stronger evidentiary basis for some of these reasons, none of them are explanatory slam dunks, so to speak. At minimum, this means that there’s a compelling case for analytical caution and policy humility when reaching conclusions about the causes of China’s conduct and making recommendations about how to handle Beijing.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

Thanks for so thoroughly unpicking that issue.

I suspect that China sees no hope that we will ever be trustworthy, and has given up even attempting to dampen Australia's public hostility and duplicity.

America's allies are a lost cause at the moment. No point in beating a dead horse.