China's CPTPP pressure to mount, warming wine prospects, and ministerial meetings

Fortnight of 17 to 30 April 2023

Australia should prepare for mounting CPTPP pressure from China

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade spokesperson providing comment to BCB on 17 April in response to a question about Australia’s position on Taiwan’s bid for membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP):

“The focus of the CPTPP members remains the ongoing accession negotiations with the United Kingdom. No decisions have been taken by the CPTPP membership on applications beyond the UK accession process.”

Quick take:

Even in the wake of the substantial conclusion of negotiations for the United Kingdom’s CPTPP accession, Australia and other members won’t be drawn on future candidatures. As with Taiwan’s application, not publicly taking an individual position on China’s CPTPP bid is understandable and probably just good diplomacy. This is especially so given: the awkward combination of the possible trade rewards of China’s membership and its sustained economic coercion of Australia; the trade grouping’s consensus-based decision-making; and big outstanding questions about China’s ability to meet CPTPP standards. An equivocal approach to Beijing’s bid might make even more sense considering that taking a clear position risks inviting questions about Taipei’s concurrent bid, which is arguably more plausible than China’s yet also opposed by the Chinese government. But although a considered non-position (publicly, at least) might make the most diplomatic sense, it’s likely to come under growing pressure from China.

The optimistic assessment might be that countries like Australia will be able to publicly sidestep the ticklish issue of China’s CPTPP bid. The CPTPP’s rules on issues like labour, state-owned enterprises, and e-commerce, among others, mean that China’s CPTPP membership might be a nonstarter. If at least some CPTPP countries can’t be swayed to seriously consider China as a prospective member, then Australia might never need to publicly reveal its cards. Yet even if this scenario remains a live possibility, at least three factors suggest that Beijing will pile up the pressure on Canberra to back its CPTPP bid:

Beijing appears determined to join. As I’ve previously noted, Beijing’s CPTPP bid was included in the Chinese government’s 2023 Work Report. Although this doesn’t necessarily mean that China will devote adequate energy to the task of getting into the CPTPP, it nevertheless looks like a serious signal of intent. This is further underscored by recent high-level messaging. As Vice Minister of Commerce Wang Shouwen put it: “We hope that all 11 [CPTPP] member countries can support our joining.” This follows speeches from President Xi Jinping himself in recent years (e.g., here and here) making clear Beijing’s commitment to joining the CPTPP. Closer to home, China’s Consul General in Perth, Long Dingbin, also emphasised that the CPTPP is part of Beijing’s plans for “high level opening up,” writing on 17 April in The West Australian that “China will … actively promote accession to the [CPTPP] and other high-standard economic and trade agreements.” Is it possible that China is simply flying trial balloons and isn’t determined to get in? Absolutely. But if that was the case, I’d expect to see references to CPTPP accession restricted to quasi-authoritative Chinese media reporting or the odd comment in a press conference. A strong Work Report reference, declared determination from President Xi, and aspirational comments from a Vice Minister and Chinese diplomats suggest that China is serious about joining the CPTPP.

Quite aside from China’s intent, CPTPP entry would also serve some of Beijing’s overarching national objectives. China both touts itself as a leading global champion of rules- and institutions-based trade liberalisation and lambasts the United States as a bad faith trade actor. CPTPP membership would aid China’s efforts to burnish its credentials and tar the United States. Entry would allow China to more convincingly present itself as an international trade rule maker and liberaliser, while also underscoring the patchy US record on international trade liberalisation in recent years, which includes hasty US withdrawal from the CPTPP’s predecessor agreement in January 2017. Moreover, CPTPP accession would expand China’s trade connections with a range of close US allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific, including Japan, Australia, Singapore, and New Zealand. Although such increased trade connectivity might not proportionally increase China’s influence and reduce US influence, it could incrementally advance Beijing’s apparent objective of drawing regional countries, including US allies and partners, away from the United States and closer to China. The history of the CPTPP would also make accession especially useful from the point of view of Chinese diplomacy. What better way to undermine the United States’ reputation and boost China’s credentials than joining a reborn version of a trade agreement that Washington once championed and then abandoned? With the chances of US CPTPP accession somewhere between low and non-existent regardless of whether President Joe Biden holds the White House after 2024, China has an opportunity to simultaneously enhance its own reputation and outflank the United States. Of course, none of this is to say that China’s bid is necessarily likely to succeed or that we should uncritically accept China’s characterisation of the significance of its CPTPP accession if it’s successful. But given that CPTPP membership could be a multidimensional win for China’s statecraft, there are strong grounds for thinking that Beijing will make great efforts to get in.

On top of Beijing’s intent and reasons for wanting entry, China has a compelling value proposition that it can dangle as part of its bid. Regardless of China’s economic coercion of Australia and its uncertain ability to meet CPTPP standards, any prospect of greater access to the gargantuan Chinese market is likely to turn many heads. To be clear, I’m not saying that China’s economic weight should matter to CPTPP members when considering whether to support China’s bid. (As an Australian analyst, I can, unsurprisingly, think of a few reasons why one ought to at least be cautious about deepening export dependence on China.) Yet regardless of the questionable quality of China’s record of abiding by trade rules, quantity has a quality all of its own, as the (likely) apocryphal Joseph Stalin quote goes. For some CPTPP capitals, the economic gains of additional access to the huge Chinese market might be enough to overlook China’s economic coercion and difficulty meeting some CPTPP standards. Canberra, Tokyo, and Ottawa have experienced the sting of China’s coercive trade practices, and so might maintain that China’s trade malfeasance alone is grounds enough to rule out Beijing ever joining to the CPTPP. But not all CPTPP capitals will necessarily think this way. And even in Australia—the biggest target for Beijing’s economic coercion in recent years—the allure of greater access to the Chinese market and the prospect of enmeshing China in more trade rules might be enough to convince at least some stakeholders to swing behind its CPTPP bid. China’s Perth Consul General Long was certainly pushing in that direction in the op-ed mentioned above when he wrote: “It is forecast that in the coming decade China will import over USD 22 trillion of goods, which means huge opportunities for Australia and other countries around the world.” This is not to predict how Australia or other members will assess China’s CPTPP bid, much less to recommend that they approach it in a certain manner. But it is to suggest that China has realistic reasons for thinking that it could win support among CPTPP states.

Of course, it’s entirely possible that Beijing’s bid will quickly flounder because of China’s recent track record of economic coercion against a founding CPTPP member and compliance difficulties with various aspects of this free trade agreement. For now, however, an alternative looks more likely: China will prosecute a sustained and determined campaign to convince CPTPP members to back its bid and many capitals will give Beijing a serious hearing. This CPTPP campaign is by no means poised to succeed. But even if Beijing’s bid is slow, halting, and ultimately unsuccessful, we should expect the pressure to mount on even the most sceptical of CPTPP capitals. And Beijing is almost certainly eying Canberra off as a prime target for such a campaign for CPTPP entry.

Addendum: If I’m right, and China doubles down on its CPTPP bid, should we reinterpret the recent warming of the Australia-China relationship? In other words, is it possible that Beijing has pursued relationship repair with Canberra to, among other goals, remove one of the biggest hurdles to its CPTPP accession? We’re admittedly entering the speculative realm. There’s no concrete evidence on the public record (that I’ve seen) clearly suggesting that Beijing’s rehabilitation of ties with Canberra is part of a calculated strategy to join the CPTPP. And I’m certainly not privy to any private information to that effect. But while there’s no hard data confirming this hypothesis, it’s at least consistent with the available evidence. Beijing’s pursuit of relationship repair with Canberra is precisely the kind of course correction that one would expect if China was intent on getting into the CPTPP. The timelines even (roughly) match: China formally launched its bid for CPTPP membership in September 2021 and it was only three months later in December that year that the first signs of Beijing’s change of diplomatic tact towards Canberra appeared. To be sure, any open-source assessment that Beijing sought to repair ties with Canberra to improve its CPTPP chances would need to be at best low-confidence, especially considering the many plausible alternative explanations for China’s changed approach. I simply (very tentatively) float this as a possible additional explanation for Beijing’s changed behaviour.

Sommeliers and smiles

Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry Senator Murray Watt speaking to The Australian after his 17 April meeting in Canberra with Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs Vice Minister Ma Youxiangn:

“I definitely felt there was a sincere desire for co-operation and to move forward and deal with some of those trade impediments that have been in place for a while.”

Quick take:

Repair of the Australia-China relationship continues apace with yet another seemingly chummy meeting. Both the Australian and Chinese principals put on warm smiles for the cameras and hopes were expressed about the promising prospects of additional trade between Australia and China. The official Australian readout and press reporting didn’t indicate any immediate and specific breakthroughs regarding China’s trade restrictions. Yet the atmospherics and messaging of this latest high-level meeting are consistent with what I’ve previously argued is likely to be a progressive, albeit potentially incomplete, dismantling of China’s trade restrictions in 2023, including anti-dumping and countervailing duties on barley and wine.

The optics of the meeting seemed especially promising for Australian wine exporters hoping to get back into the Chinese market. Beyond the formalities of a ministerial meeting at Parliament House, Vice Minister Ma also went on a little jaunt to Murrumbateman. (For international readers, Murrumbateman is one of the Canberra wine region’s prime locales. And one that I can’t resist recommending if you visit Canberra.) The Vice Minister reportedly toured the Clonakilla winery and even managed to have a tipple of its product. To be clear, none of these program details massively increase the strength of my standing assessment that China’s anti-dumping and countervailing duties against Australian wine will be removed later this year. But at the very least, the optics of a Chinese vice minister sampling Australian wine would be jarring and arguably ill-advised if there weren’t already plans afoot to get those same drinks in the hands of Chinese consumers in the coming months. So, if I was an Australian wine exporter looking to get back into the Chinese market unburdened by anti-dumping and countervailing duties, I’d be feeling pretty optimistic right now.

The state of senior Albanese government engagement (so far)

Bilateral meetings between Australia and China at the assistant minister level and above since May 2022:

8 July 2022: Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong meets Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi at the conclusion of the G20 Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Bali. (The Chinese government’s readout of this meeting is available in Chinese and English.)

22 September 2022: Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong meets Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi on the margins of the 77th session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York. (The Chinese government’s readout of this meeting is available in Chinese and English.)

8 November 2022: Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong and Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi speak via telephone. (The Chinese government’s readout of this meeting is also available in Chinese. The Australian government did not release a formal readout of this meeting.)

12 November 2022: Prime Minister Anthony Albanese meets Premier Li Keqiang on the sidelines of the East Asia Summit in Phnom Penh. (The Chinese government’s readout of this meeting is available in Chinese and English. The Australian government did not release a formal readout of this meeting.)

15 November 2022: Prime Minister Anthony Albanese meets President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the G20 in Bali. (The Chinese government’s readout of this meeting is available in Chinese and English.)

21 December 2022: Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong meets Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi in Beijing for the Sixth Australia-China Foreign and Strategic Dialogue. (The Chinese government’s readout of this meeting is available in Chinese and English.)

20 January 2023: Assistant Minister for Trade Tim Ayres meets Vice-Minister for Commerce Wang Shouwen in Davos. (Meeting also referenced by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.)

6 February 2023: Minister for Trade and Tourism Don Farrell has a video call with Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao. (The Chinese government’s readout of this meeting is available in English and Chinese.)

2 March 2023: Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong meets Minister of Foreign Affairs Qin Gang in New Delhi on the sidelines of the G20 Foreign Ministers Meeting. (The Chinese government’s readout of this meeting is available in Chinese and English.)

30 March 2023: Assistant Minister for Trade Tim Ayres meets Vice-Minister for Commerce Wang Shouwen at the Bo’ao Forum. (Minster Ayres’ press release from his Bo’ao Forum visit is available here.)

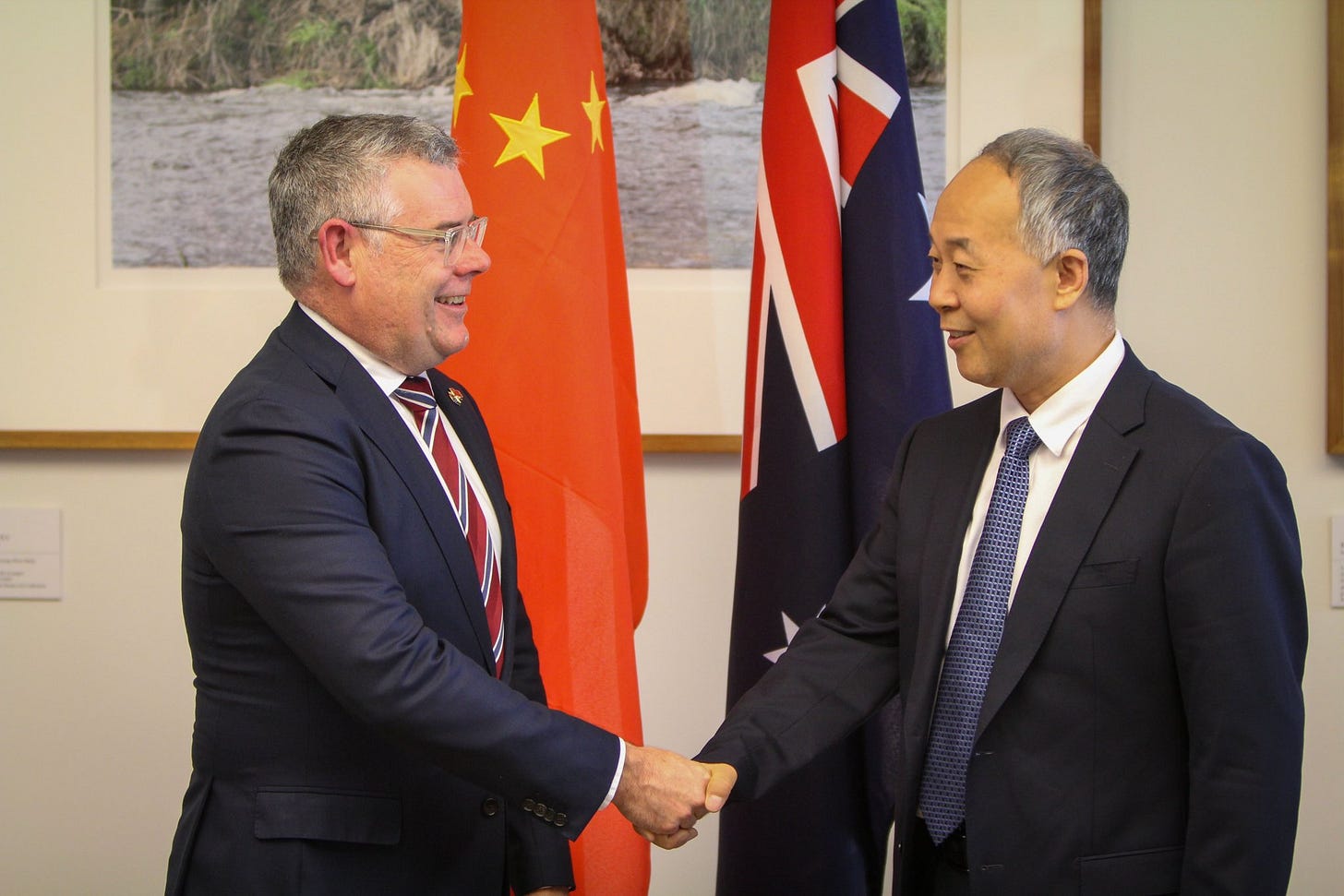

17 April 2023: Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry Senator Murray Watt meets Vice Minister for Agriculture and Rural Affairs Ma Youxiang in Canberra. (Minister Watt also tweeted about the meeting.)

Quick take:

In less than a year, the prime minister and his ministers and assistant ministers have met at least 15 times with their Chinese counterparts. Coming from a standing start of no political engagement at all since the January 2020 foreign ministerial phone call, this is a dramatic revival of contact. To note, the above includes both in-person, online, and phone engagements, but does not include indirect contact in the form of congratulatory letters and the like. The above also doesn’t include meetings below the assistant minister level or multilateral meetings at which Australian and Chinese principals were seated at the same table but didn’t have a dedicated bilateral meeting. I’m relatively confident that the above captures all the publicly recorded ministerial meetings in the foreign affairs, trade, and defence portfolios, but please correct me if I’ve missed anything, including meetings from other portfolios.

Notably absent from the above list is a leader-level visit to either Australia or China and an in-person meeting at the full ministerial level in the trade portfolio. But given recent comments from Minister for Trade and Tourism Don Farrell, it seems likely that he’ll visit China shortly (possibly in the next week) and that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese will make the trip before the end of the year. Of course, this massive spurt of high-level engagement hasn’t dissolved the bulk of the most severe disputes between Canberra and Beijing. Still, as well as the likely resumption of a range of formalised dialogue mechanisms and the progressive, albeit tentative, removal of trade restrictions, political engagement in the Australia-China relationship is returning to something approximating its pre-2020 rhythm.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

A wonderfully Aussie take on affairs!

Here's a sample of why China resorted to 'coercion':

Canberra paid anti-China think tanks to spread false reports and peddle unsubstantiated allegations about Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

Canberra funded investigations into so-called 'China infiltration' designed to manipulate public opinion against the country.

Australian police made pre-dawn searches and conducted reckless seizures in Chinese journalists' homes without charge, explanation, or apology.

Australian politicians made repeated, false allegations about Chinese cyber attacks.

Australia condoned and repeated government-funded NGOs' outrageous condemnations of the governing party of China.

Australia shrugged off hundreds of racist attacks against Chinese and Asian people.

During a riot started by US and Taiwanese agents in the Solomon Islands, Australian officials told Solomons PM Sogovare that they would not protect Chinese infrastructure projects.

When an Australian politician, Shaoquette Moselmane MP, repeated the WHO’s praise of China’s Covid Zero, forty police arrived at his home and stayed for 13 hours. They brought sniffer dogs, took hair and dust samples from his car, searched the car engine and door rubbers, had a helicopter hovering and raided his parliamentary office, and froze the Moselmane family’s bank accounts. Minister of Defence Peter Dutton told a reporter, “You can’t have an allegiance to another country and pretend to have an allegiance to this country at the same time”. No charges were ever brought against Mr. Moselman, nor apology made to his terrified family.

Australia stigmatized normal cooperation and imposed restrictions, like the revocation of Chinese scholars’ visas – which caused a scandal in China

Australia launched intimidatory predawn searches and reckless seizures of Chinese journalists’ homes and properties without charge or explanation.

Australia’s national lab, the CSIRO, told staff it will not renew its climate research partnership with the Qingdao National Marine Laboratory, following an assertion by ASIO’s Mike Burgess that ocean temperature modelling could assist submarine operations against Australia (a decision met with robust criticism by Australian scientists).

Read the whole list here: https://herecomeschina.substack.com/p/what-australia-did-to-china-c64?sd=pf