A (partial) history of high-level engagement and tactical diplomatic inducements

Fortnight of 28 February to 13 March 2022

Australia and China hand in hand

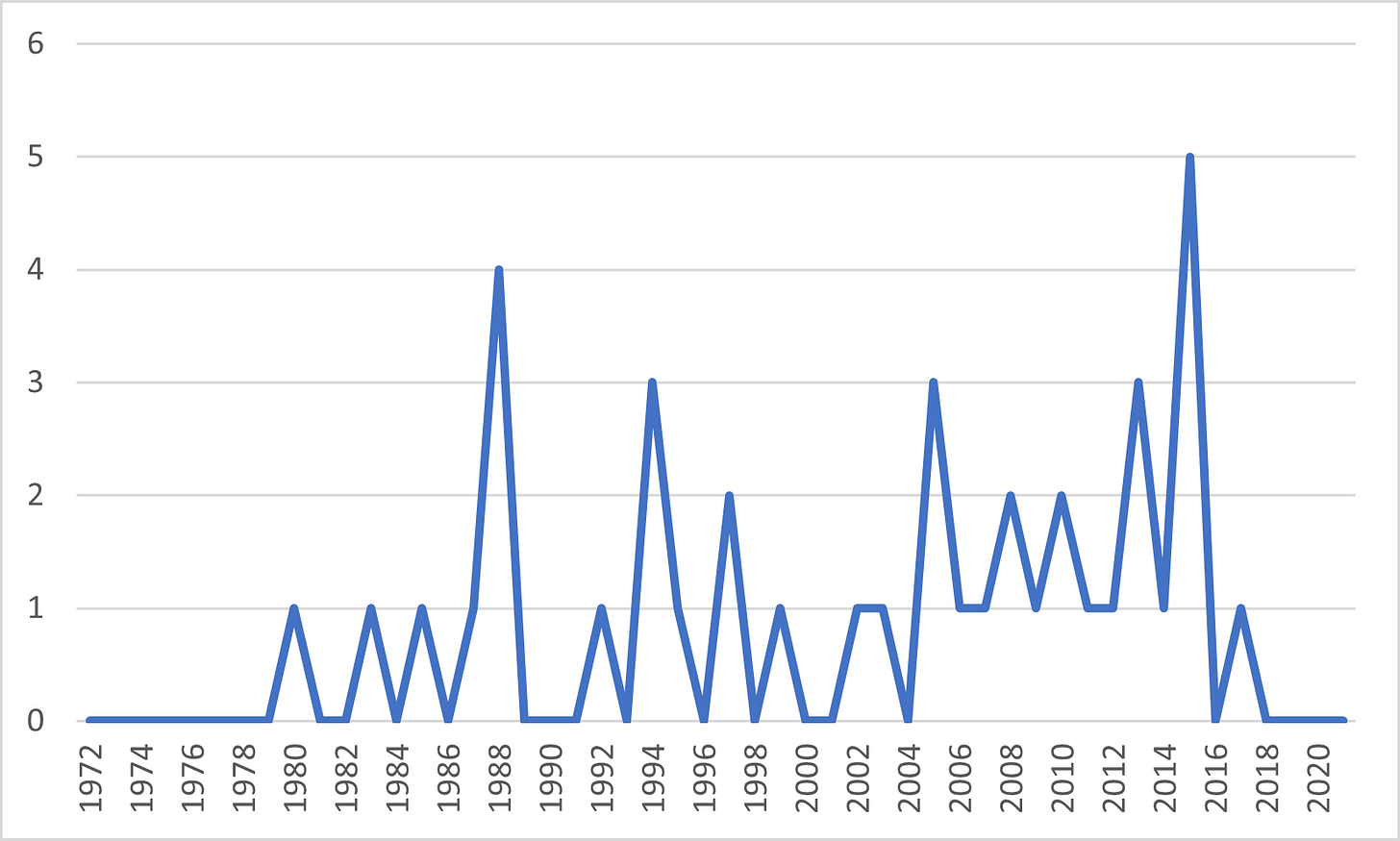

The number of face-to-face meetings between Australian governor-generals and Chinese leaders and senior officials*, 1972-2021:

Quick take:

The above graph is still very much a work in progress and doubtless misses some meetings between Australian governor-generals and Chinese leaders and senior officials. This is especially likely to be true for the first decade or so of the relationship. For example, I haven’t yet tracked down whether Politburo members Ulanhu and Chen Muhua met the Governor-General during their respective visits to Australia in 1977 and 1979. Any corrections or additions that readers might be able to offer would be gratefully received. I’ll continue updating and correcting the website version of this graph as I capture more datapoints.

Meetings between Australian governor-generals and Chinese leaders are, of course, not the most significant measures of the state of high-level relations between Australia and China. Still, these meetings tell an instructive story given the importance that the Chinese government and communist party appear to attach to engagements with the (largely) ceremonial position of the Governor-General. But I fully take the point about the limited analytical value of this measure alone. To that end, I’ll be adding data on prime ministerial engagement in the coming weeks to provide a fuller picture of the history and trajectory of Australia-China diplomatic relations at the leader level.

Noting all these caveats about the limitations of this data, here are a few preliminary observations based on the data of Governor-General meetings:

Australia is currently experiencing the most sustained period since 1980 without engagement between the Governor-General and Chinese leaders and senior officials. This historical contrast is especially striking considering that governor-generals met with Chinese leaders and senior officials on average nearly two times each year in the ten-year period 2006-15.

At the Governor-General level, the freeze in high-level diplomatic relations between Canberra and Beijing after the Tiananmen Square Massacre only lasted three years (1989-91). This current curtailment of engagement at the level of Governor-General has lasted four years and counting.

If Ulanhu and Chen Muhua met the Governor-General during their respective visits to Australia, the current period would be the most sustained period since Mao Zedong’s death without engagement between the Governor-General and Chinese leaders and senior officials.

The above graph is from the first tranche of a dataset on the history of Australia-China diplomatic relations that I’ll be making progressively available on Beijing to Canberra and Back’s companion website. The website is still in a very, very, very beta and lo-fi mode for now. But it’ll be progressively refined and expanded in the coming weeks/months. The intention is to build it into an interactive repository of political, diplomatic, and economic data charting the history and trajectory of Australia-China relations. I’ll also add analysis to that website from this newsletter and elsewhere. In addition to the above data, the website will eventually feature other measures of the history and trajectory of Australia-China diplomatic relations. Regarding the above and other metrics of the relationship, many thanks to Gatra Priyandita and other researchers for their assistance compiling elements of this data.

* For the purposes of this graph, Chinese leaders and senior officials are defined as any Chinese Communist Party official at the level of Politburo or above and any Chinese government official at the level of Minister or above.

Getting relations back on track

The Chinese Embassy’s readout from Minister for Foreign Affairs Marise Payne’s 9 March meeting with Ambassador Xiao Qian:

“This year marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Australia. It is hoped that the two sides will work together to review the past and look into the future, adhere to the principle of mutual respect, equality and mutual benefit, and make joint efforts to push forward China-Australia relations along the right track.”

Quick take:

The Chinese Embassy’s readout of this meeting was broadly optimistic. The upbeat tone and calls to get bilateral relations back on the right track were consistent with Ambassador Xiao’s messaging since arriving in country. Although the Chinese Embassy’s rendering of the Foreign Minister’s remarks wasn’t negative per se, it seems to suggest that her positivity was more muted. The Foreign Minister’s website doesn’t mention the meeting, while the Chinese Embassy observed that Minister Payne welcomed the Ambassador, affirmed the importance of bilateral relations, offered Canberra’s perspectives, and expressed hope for enhanced communication and exchanges.

Canberra isn’t necessarily rejecting Beijing’s call for an improvement in bilateral relations. Canberra wants ministerial dialogue and, of course, a rolling back of China’s trade restrictions. As the Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment Dan Tehan said back in February: “Well, obviously I wrote to my Chinese counterpart over two years ago now saying that we would be happy to sit down and work through all the disputes that we currently have with China.” But it’s also clear that the Australian government isn’t willing to predicate an improvement in the relationship on the policy and political changes for which the Chinese government has previously called.

Of course, all of this leaves unanswered the question of whether the “joint efforts” suggested by Ambassador Xiao would require Canberra to act on Beijing’s past complaints—to which the Australian government has repeatedly and firmly rejected acceding. If it isn’t already happening at the official level, perhaps there’s a case for Beijing to more clearly and explicitly detail how it sees these “joint efforts”. Failing that, Australians and their leaders will likely imagine that Beijing’s asks haven’t shifted since November 2020. And, as a result, no Australian government is likely to receive a popular mandate to make such “joint efforts”. Over to you, Beijing.

Inducements Vs. compromises

Minister for Foreign Affairs Payne delivering the fifth Tom Hughes Oration on 1 March:

“There is sacrifice involved [in introducing sanctions against Russia] – just as there has been in Australia’s response to China’s coercion over the part [sic] two years. We recognise the impact, for example, that China’s unjustified trade measures have had on some sectors in our economy, and the Government has worked and will continue to work closely with them to mitigate that impact.”

“But as a nation, we have stood firm. And consistency is key.”

“This has been the right decision – sometimes in the face of criticism from voices who have said we should make compromises to repair the relationship with China.”

Quick take:

Two big (and usually unanswered) policy and political questions loom over contemporary debates about the Australia-China relationship: 1. Which specific concessions would be enough to convince China to end its diplomatic freeze and economic coercion of Australia? 2. Should Canberra make these concessions? Despite their analytical and moral importance, I’m doubtful that these kinds of questions are the most productive approach to interrogating Canberra’s current China strategy. Australians and their governments understandably don’t want to compromise on their values and interests. That’s especially the case when it comes to Beijing’s complaints regarding fundamental priorities such as Australia raising human rights concerns and independently making decisions on foreign investment. This makes debate about many possible compromises moot, politically speaking at least.

But this leaves unanswered a question that is (in my view) too rarely posed: Could Canberra offer tactical inducements that would improve the Australia-China relationship? Such tactical inducements could be statements or initiatives designed to appeal to Beijing without changing Canberra’s current policy or political positions in relation to China. An example of such a tactical inducement might be the Australian government’s regularly repeated talking point praising China for its massive poverty alleviation achievements (e.g., here and here). As well as providing the government with something positive to say about China to a domestic Australian audience, rhetorical manoeuvres like this extend a diplomatic olive branch to Beijing without requiring any compromises on Canberra’s political and policy positions.

What other tactical inducements could Canberra offer? Here are three (very tentatively) offered possibilities:

Offer regular but measured support for China’s limited financial sector reforms. Of course, these reforms could go much further. But (partial) liberalisation has occurred and is likely a net positive for the Chinese economy and people, as well as being (at least somewhat) beneficial for Australia and the global economy. Such positive messaging probably wouldn’t cost Canberra more than a few talking points and would also likely be noted and appreciated by Chinese officials.

As well as noting China’s role as the world’s largest carbon emitter, acknowledge and commend Beijing for its ambitious goals of reaching net zero by 2060. Questions can certainly be asked about both the feasibility of such goals and whether they actually need to be even more ambitious. But encouraging China on this front would likely be welcomed by Beijing (and withholding such praise is unlikely to seriously incentivise Beijing to raise its emissions reduction targets further).

Related to 2 but more substantive: Propose and pursue the resumption of the Australia-China Ministerial Dialogue on Climate Change. Last held (I think) in 2014 during the Abbott government, such a dialogue would be a handy way to reestablish ministerial contact in a policy arena in which Australia’s and China’s goals and interests are (broadly) aligned. As well as an opportunity to pursue a cooperative agenda on combatting climate change, such a dialogue might allow Canberra to again start prosecuting a broader set of its interests with Beijing at the ministerial level.

To be sure, it remains unclear whether any such tactical inducements would convince China to change its approach to Australia. Afterall, the Prime Minister and his ministers have been lauding China’s poverty reduction achievements for many months without (seemingly, at least) any positive effects. We therefore admittedly don’t have an especially strong reason for thinking that inducements like the above would significantly shift the trajectory of Australia-China relations. But such uncertainty isn’t a reason for ruling out these kinds of tactical inducements. These inducements are designed to be low cost. They don’t (so far as I can see) compromise on Australia’s fundamental interests and values. And as with positive diplomatic rhetoric on poverty reduction, the worst-case scenario would involve Australia expending modest diplomatic effort for no return.

Having said all of that, the above suggestions might be dead on arrival. The domestic politics of China policy in Australia means tactical inducements directed at Beijing may be unpalatable, especially during this testy election season. Moreover, recent stories of an Australian proposal to revive an Australia-China senior officials dialogue in the Pacific suggest versions of what I’ve proposed might have already been considered and rejected or tried privately and failed. Notwithstanding those caveats, I still think there’s a case for thinking about ways Canberra could appeal to Beijing to resume normal diplomatic and trade relations without Australia having to compromise on any of its values and interests. Australian exporters have for the most part been able to redirect to alternative markets in the wake of China’s trade restrictions and Australia-China relations at the institutional, people-to-people, and state and territory levels have survived a sustained absence of ministerial- and leader-level contact at the federal level. But assuming Australia doesn’t have to compromise on its values and interests, it’d still be preferable to get back to regular diplomatic and economic programming.

As always, thank you for reading and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.