Ongoing relationship repair, enduring and emerging tensions, and thank you

Fortnight of 27 November to 10 December 2023

Coal exports and ongoing relationship repair

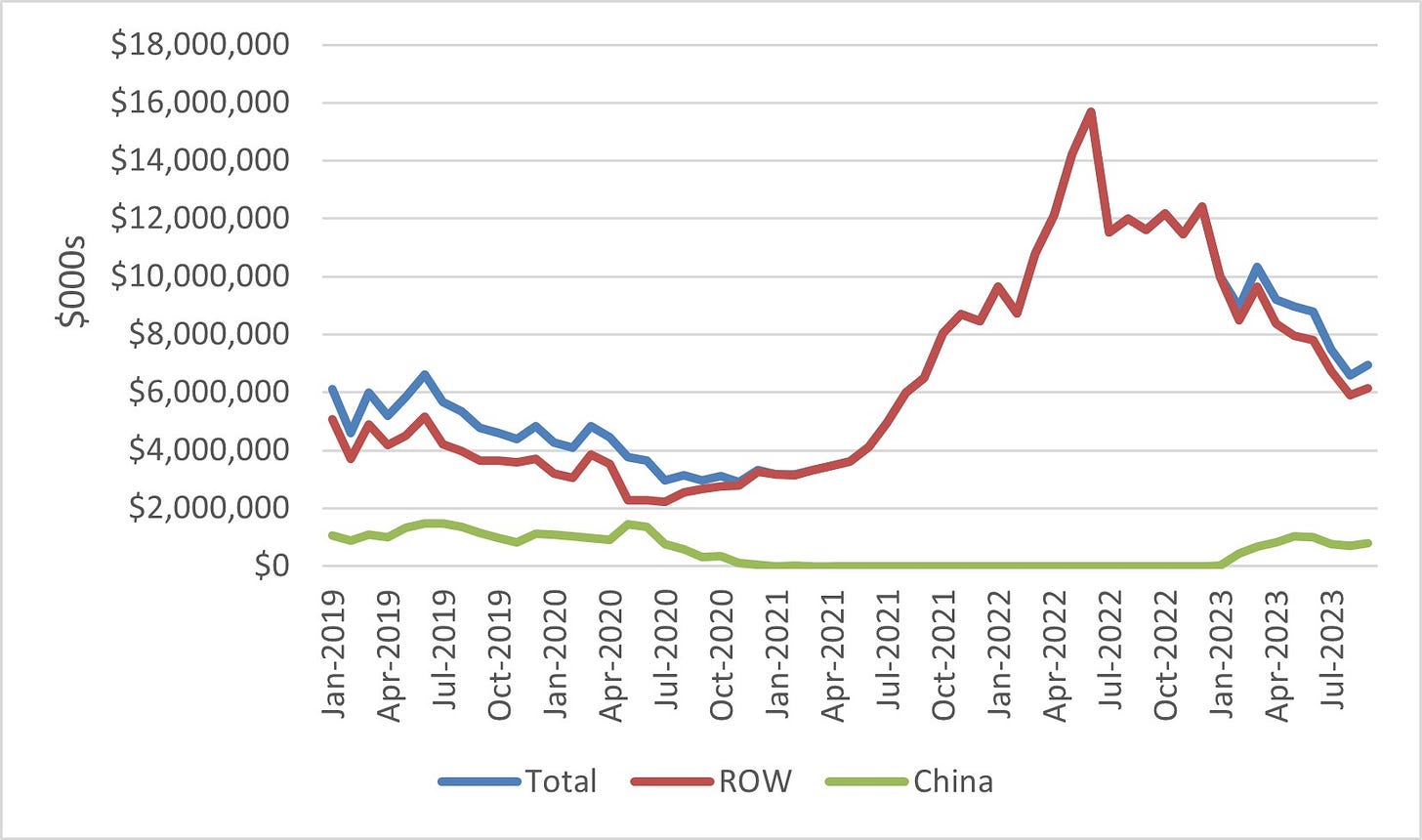

The monthly value of Australia’s coal exports to China, the rest of the world, and total, January 2019 to September 2023:

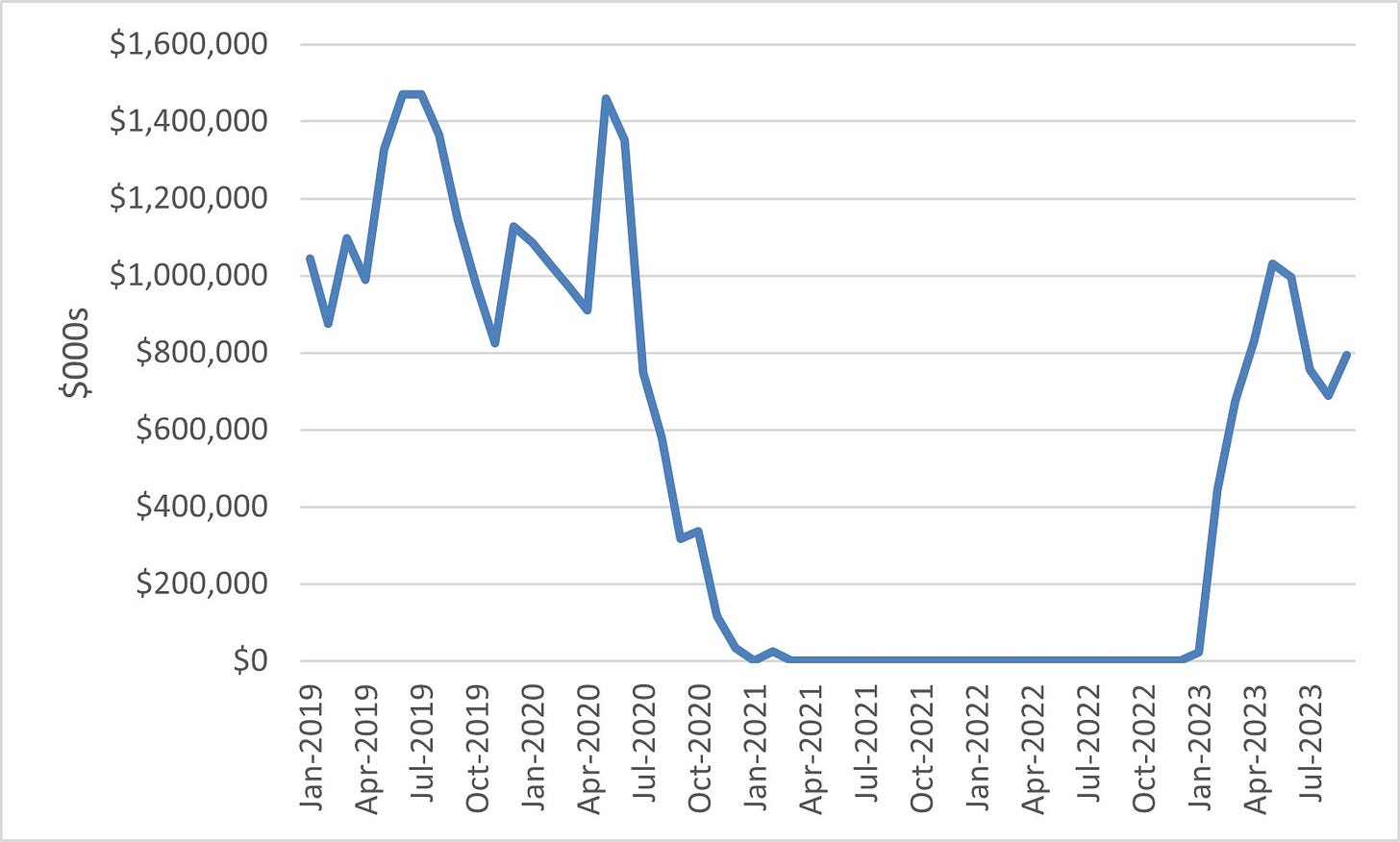

The monthly value of Australia’s coal exports to China, January 2019 to September 2023:

Quick take:

Per the first graph, it was ironically when China shut its doors that the monthly value of Australian coal exports peaked. Of course, correlation isn’t causation, and this doesn’t mean that China’s economic coercion was good for Australian coal exporters. Although 2021-22 saw constrained Australian coal production and a decline in the volume of this export, it also saw a massive surge in prices. The average spot price for Australian thermal coal in 2021 was more than double the 2020 level, while for coking coal the 2021 average spot price was 1.8 times the 2020 level. This once again underscores Australia’s good fortune as it navigated economic coercion. Not only did China’s trade restrictions mostly target (with some notable exceptions) fungible commodities that could relatively easily redirect to alternative markets, but many of those exports benefitted from strong global demand and high prices.

Among other things, the second graph highlights how quickly Australian coal burst back into the Chinese market after the removal of trade restrictions. Except for a tiny blip of $25 million worth of Australian coal that apparently went to China in February 2021, this export didn’t get into the Chinese market between January 2021 and December 2022. Despite this near-total freeze for two years, Australian coal exports to China spiked dramatically almost as soon as they were allowed back in during the first half of 2023. The average monthly value of this export now is admittedly still below the level prior to China’s economic coercion campaign. And yet the monthly value surpassed the $1 billion mark in May 2023—mere months after Beijing lifted the ban.

Along with rebounding coal exports, a range of other indicators point to the ongoing repair of the Australia-China relationship. On 9 December, the Minister for Trade and Tourism Don Farrell trumpeted that Australian barley was again getting back into China in significant quantities. This followed the release of Austrade’s tourism forecast predicting rapidly rising exports to the Chinese market. Austrade expects 1.89 million visitors from China in 2028, which would see the Chinese market account for 16% of total arrivals and again become the largest single source of tourists. Although there aren’t yet concrete signs of relief for Australian wine and lobster exporters, it’s nevertheless been reported that three (though not all) of the previously suspended Australian abattoirs will again get access to the Chinese market. Recent weeks also saw other signs of relationship repair, including high-profile Chinese cultural diplomacy in Australia and upbeat messaging from China’s Ambassador Xiao Qian.

In addition to the extensive outreach in Australia late last month (e.g., here, here, here, here, here, and here) from Liu Jianchao, Head of the International Department of the Chinese Communist Party, there are strong indicators that leader-level contact will continue apace in 2024. As previously floated in BCB, it’s looking more likely that Premier Li Qiang will visit Australia next year. Recounting his recent conversation with President Xi Jinping and Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said on 18 November: “We spoke about Premier Li coming to Australia next year, now that the leaders’ meetings have been resumed.” Given that this prospective visit is being discussed at the highest levels and flagged publicly, it looks increasingly like a lock (short of some kind of calamity in Australia-China relations). And assuming it occurs, it’ll be the most senior Chinese political visit since Premier Li Keqiang came in March 2017.

Enduring and emerging tensions

A spokesperson for Treasurer Jim Chalmers on 27 November in relation to a Foreign Investment Review Board investigation into claimed efforts by China-linked Yuxiao Fund to increase its stake in Australian rare-earth elements miner Northern Minerals:

“Maintaining strong compliance with Australia’s foreign investment legislation is a priority for the Australian government to help ensure that investments are consistent with the national interest.”

Quick take:

Despite ongoing relationship repair in the trade, diplomatic, political, and related arenas, all manner of fissures look set to test ties in 2024. I’ve written regularly in BCB about a familiar and extensive list of enduring points of bilateral tension. I won’t enumerate and unpack these again here, but they include all manner of disputes ranging from China’s treatment of detained Australians (e.g., here and here) to Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines (e.g., here and here). On top of these, there are also long-simmering disagreements that have extra heat because of current events. These include contemporary claims and counterclaims about encounters between the Australian Defence Force and the People’s Liberation Army, concerns about China’s South China Sea assertiveness, and cyberattacks and attributions. Added to these recent flareups, largely dormant points of tension are liable to intensify next year, depending on international and domestic events. These might include a renewed domestic push to further limit access to the Australian market for Chinese-owned apps or extra international pressure on Australia to join sanctions targeting Chinese officials and entities over human rights abuses.

But the bilateral relationship is probably even more fragile than these familiar points of tension might suggest. New(-ish) and emerging irritants look set to bubble up in the coming months as well. Among others in my watching brief for early next year, three look especially likely to surface:

Wrangling over renewed efforts by Chinese or China-linked entities to increase or acquire stakes in Australian critical minerals miners, including potential divestment orders on existing holdings from Australia in response (e.g., here and here);

Ongoing consideration in Canberra of outbound investment restrictions into the Chinese market—either prompted by domestic ethical and political concerns or US efforts to encourage international restrictions on capital flows into select Chinese technology companies (e.g., here and here); and

Possible pressure on Australia to join a likeminded walkout of the China-led (for want of a better descriptor) Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, or at least support a push for internal reform (e.g., here).

It’s entirely possible that none of these points of friction will really burn in 2024. Yet the above is probably far from the complete list of the sources of bilateral tension coming through the pipeline. So, the chances of one of these or another rub point starting to chafe are high. To be sure, the bilateral relationship might not collapse all over again. Still, I’d be willing to wager that one or more of these or another new sensitive issue will cause (at minimum) considerable consternation in Canberra and Beijing and again stress test ties next year. Given all the economic, political, and diplomatic reasons that both Australia and China have for keeping ties together, ongoing relationship stabilisation looks like the most likely bilateral path in 2024. But the long and lengthening list of old and new sources of tension suggests that it’ll remain a precarious form of stability. As I recently said to my Australian National University colleague Darren Lim on the Australia in the World podcast: If bilateral ties have stabilised, then they’re probably stable in much the same way that a dicey Jenga tower might be stable before it collapses.

Thank you

With the temperature climbing past 35 degrees Celsius as I write these words on a dry December day in Canberra, this will be the last edition for 2023. BCB will go on an extended southern summer hiatus over the Christmas-New Year period, returning to your inboxes sometime around the end of January 2024. Roughly two and a half years after I started writing BCB, it now has a back catalogue of more than 70 editions totalling upwards of 135,000 words. To be fair, that second number has likely been inflated by at times verbose prose. And yet despite some linguistic inefficiencies, BCB has still covered (to varying degrees of detail) nearly every major development of the last 30 or so tumultuous months of the Australia-China relationship. All going well, it’ll keep doing the same in 2024.

Since its inception in May 2021, BCB has been a one-person show. However, I’m the first to admit that absolutely every edition has benefitted from insights and analysis from a kaleidoscopic range of sources. As the sole researcher and writer, I take full responsibility for any errors. But BCB would’ve been a shadow of itself if not for the work of so many brilliant journalists, academics, think-tankers, and others. Thank you for your invaluable contributions to the debate. Thanks also to all of BCB’s readers. Whether you love or loathe this newsletter (or regard it with relative indifference), thank you for your time and attention. In a world of ever-more China analysis, it’s been a pleasure and a privilege having you along for the ride.

Thanks to my colleagues, co-authors, and intellectual sparring partners at the Australian National University and across the academic, think-tank, business, media, activist, and policy worlds. You’re too many to mention individually (and I know that many of you would be aghast to see your names listed here in black and white). But you’ve been an essential source of advice, education, and inspiration. Finally, and most indispensably, thanks to my boss and collaborator, Professor Anthea Roberts. To put it simply (and accurately), there’d be no BCB without Anthea. Of course, don’t blame her for any off base analysis I might have written these past few years. But equally know that not even one edition of BCB would’ve been possible without her support.

I’m looking forward to picking up the conversation in 2024. And in the meantime, stay safe and take care of each other.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

Merry Christmas and a happy new year. Looking forward to more good reading in 2024.

Thanks for the analysis and summary, greatly appreciated. I hope you and your family have a lovely Christmas break.