Tactically timed investment rejections, a leader-level visit to China, and barley exports

Fortnight of 10 to 23 July 2023

The tactical timing of Australia’s investment rejections

Treasurer Jim Chalmers speaking about Australia-China ties to the ABC’s Sarah Ferguson on 18 July:

“[O]verwhelmingly, this is a relationship, a trading relationship and an economic relationship that serves Australia very well. I believe it serves both countries very well.”

Quick take:

Notwithstanding the noticeably upbeat tone of this assessment of the Australia-China relationship, it wasn’t a dramatic deviation from Canberra’s typical messaging. Although Prime Minister Anthony Albanese regularly insists that “we’ll disagree where we must,” he’s also fond of talking up the importance of Australia-China trade ties. One of his regular refrains is that “trade to China is more than … the next three highest trading partners combined. So it’s in Australia’s national interest to have good economic relations and to trade with China”. Yet given the investment rejection that was about to be publicly announced, it’s hard not to see Treasurer Chalmers’ sunny 18 July comments as also being aimed at pre-emptively smoothing things over with Beijing.

On 20 July an order was issued that, among other actions, prohibited Austroid Corporation from increasing its stake in Australian lithium miner Alita Resources to 100% and directed Austroid to not acquire any Alita securities above its current 9.9% share. Even though Austroid is not a Chinese company, it has close links to the Chinese mining industry and key individuals there have reportedly been involved in the sale of lithium to China at significantly below market prices. One can only speculate as to the role of these and related considerations in the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) advice to Treasurer Chalmers. But the China Daily certainly interpreted the rejection as being a product of “Canberra’s anxieties about China”. The official public response from Beijing was nevertheless muted (so far as I can see). Perhaps because of a combination of: Austroid being connected to China rather than being a Chinese company; the relatively small scale of the investment; and the precedent of a rejection of a Chinese fund’s investment in another Australian critical minerals miner earlier this year. Still, it seems possible/likely that Beijing would have protested privately to Canberra about this latest rejection and that Treasurer Chalmers sought to manage China’s frustrations both in his meeting with Minister of Finance Liu Kun on 18 July and in his public messaging.

But perhaps more interesting than any of that is what this recent foreign investment rejection might reveal about Canberra’s overarching strategy for navigating Beijing’s enduring concerns about the Australian treatment of Chinese companies. Just over two weeks before the Treasurer’s Austroid knockback, it was announced that FIRB had approved Shanghai Decent Investment Group’s US$270 million stake in Australian-listed Nickel Industries. These contrasting decisions can be explained by a range of factors, including potentially the location of the respective companies’ projects and the fact that Australia categorises lithium but not nickel as a critical mineral. But regardless of the reasons, the nearly concurrent timing piqued my interest. As with the February rejection of Yuxiao Fund’s bid to increase its share in rare earth elements miner Northern Minerals and the approval of Baowu’s joint venture with Rio Tinto, this latest rejection by the Treasurer dropped around the time of the approval of Shanghai Decent’s investment in Nickel Industries.

As I wrote back in February when the Yuxiao rejection coincided with the Baowu approval: “Of course, it’s … possible that I’ve become way too conspiratorial. Maybe the timing is just happenstance and there’s been no tactical effort to massage ties with China?” I didn’t rule out coincidence then in the Yuxiao/Baowu cases and I wouldn’t rule it out now in the Austroid/Shanghai Decent cases. But with two rejections of investments from Chinese/China-linked entities coinciding with two approvals of Chinese investments, this pairing is starting to look like a pattern rather than an anomaly. The possibility of deliberate design on the part of the Albanese government is even greater given that the twinning of investment rejections with approvals is precisely what one would do if one was trying to thread the needle of rejecting Chinese/China-linked investments while also allaying longstanding and high-level concerns in Beijing about Canberra’s treatment of Chinese businesses. So, while it’s far from a clear-cut case, it seems that the Albanese government is tactically timing investment rejections to coincide with approvals in a bid to securitise the critical minerals industry, while also sending a welcoming message to Chinese investors and reducing the likelihood of getting Beijing offside.

The China trip question (again)

Prime Minister Albanese speaking to Sky News’ Andrew Clennell on 17 July:

Clennell: “… Just finally, do you think you’ll be visiting China this year?”

Prime Minister: “I think it is likely to be the case. We’re discussing arrangements between officials. I’ve been invited to go to China. …”

Quick take:

This is one of the strongest indicators yet that Prime Minister Albanese’s long-mooted China trip will go ahead as expected in the second half of the year. It comes in the midst of a range of datapoints in recent weeks that seemed to raise doubts about the visit. The delay in the removal of China’s duties on Australian barley, the arrest warrants and bounties against an Australian citizen and a resident, and the ongoing detention of Yang Jun and Cheng Lei, among other factors, prompted suggestions in some quarters that the conditions might not be right for such a prime ministerial trip. Meanwhile, Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong responded ambiguously on 13 July to questions about whether a leader-level visit would occur (e.g., here and here) and emphasised that any such trip should take place in “the most positive circumstances.” Treasurer Chalmers similarly said on 18 July that “we would like to see these trade restrictions lifted and we’d like to make progress on that in advance of a prime ministerial visit to China ideally later in the year.”

But while Minister Wong’s and Treasurer Chalmers’ comments suggest that Canberra might be using Beijing’s desire for a visit as leverage to achieve progress on trade restrictions, consular cases, and other Australian priorities, the Prime Minister’s prediction suggests that Canberra might be edging closer to accepting an invitation notwithstanding ongoing sticking points. I add the caveat “might” because I readily admit that all of this is far from clear and it’s entirely possible that I’m splitting diplomatic and rhetorical hairs in contrasting the comments from the Prime Minister and two of his senior ministers. But if Canberra was determined to achieve what it considers to be “the most positive circumstances” prior to a leader-level visit, then presumably the Prime Minister wouldn’t be describing the trip as “likely” at the same time as some of the bilateral dynamics get worse or don’t improve from an Australian perspective. Of course, this doesn’t mean that a prime ministerial trip in October/November is a lock. But it still looks like the most probable outcome despite developments that don’t augur well for key Australian priorities.

One final thought bubble: The previous bout of heightened public debate about a leader-level visit to China was in May when Prime Minister Albanese said that it “is important that any of the impediments to trade … be lifted.” Although Minister for Foreign Affairs Wong also raised at that time Australia’s expectations of “continued progress” on consular cases, the Prime Minister’s initial comments and the subsequent discussion were focussed on whether Canberra should wait for Beijing to guarantee the removal trade restrictions before committing to a leader-level visit. With Prime Minister Albanese now describing a China trip as “likely,” it seems possible that, despite the ongoing public uncertainty, Canberra has already received private confirmation from Beijing that the duties on barley and other trade restrictions will be unwound in the coming months. Such discreetly conveyed commitments from the Chinese government could explain the Prime Minister’s change of tone between May and July on the visit question. And Minister Wong’s more consistently ambiguous position could be explained by her portfolio’s particularly acute interest in making progress on a range of consular and other tough bilateral issues beyond China’s trade restrictions. If that theory is correct (a big if), then expect confirmation that the barley duties will be removed or reduced in the next few weeks, followed by more confident talk from Prime Minister Albanese about a China trip later this year. Clearly, this last paragraph has crossed over into speculation, but hopefully at least plausibly so.

Barley business booms

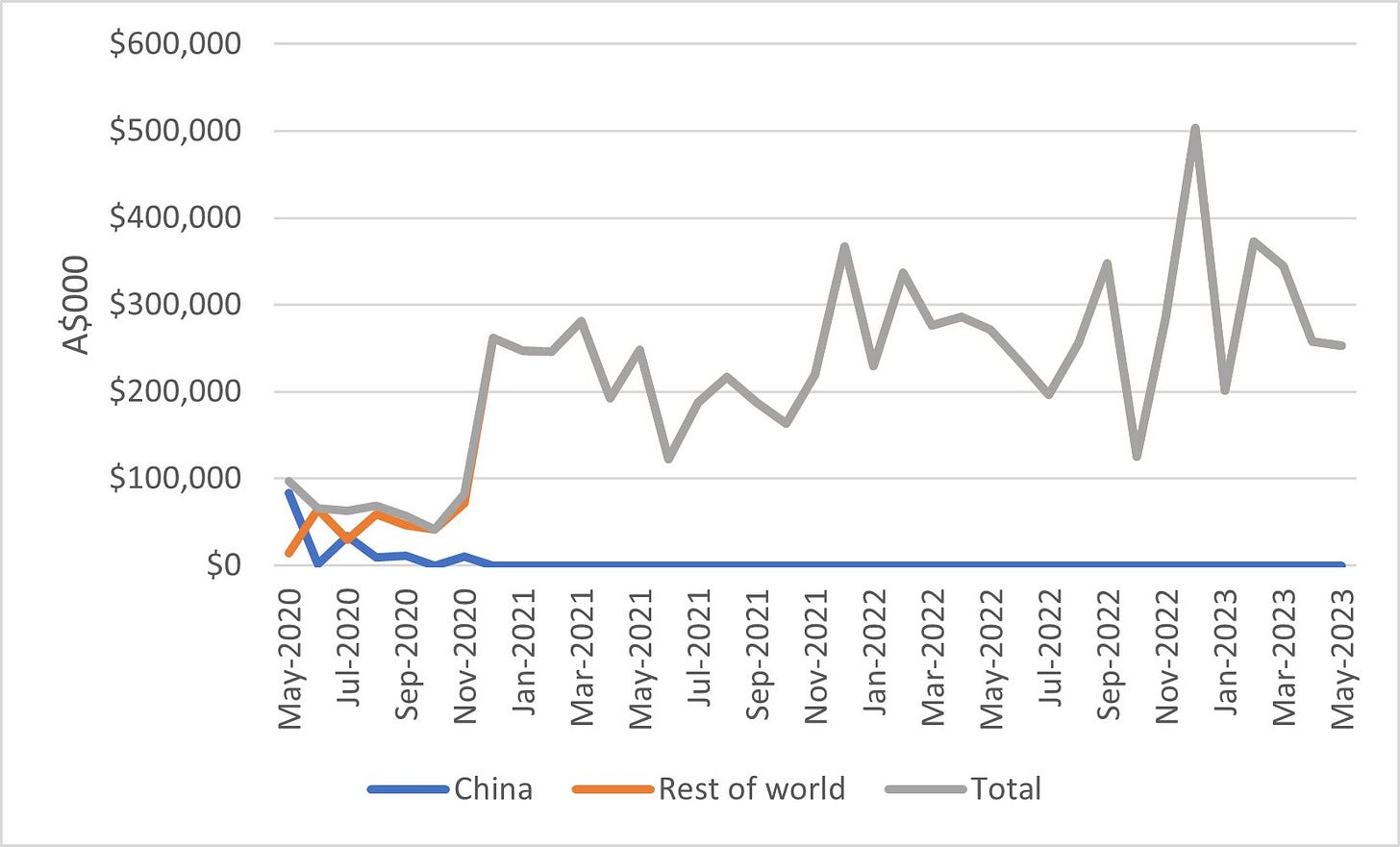

The monthly value of Australia’s barley exports (to China, the rest of the world, and total, May 2020 to May 2023):

Quick take:

The Australian government continues to press for the removal of the 80.5% barley duties as the Chinese government conducts an ongoing review. Without in any way undercutting the case for getting these (in all likelihood) politically motivated duties removed, the latest trade data underscores, among other things, how effectively Australia’s barley exporters have navigated China’s trade barriers. Despite Australian barley being priced out of the Chinese market for years due to China’s duties, these exports have redirected to alternative markets and boomed by value. Barley exports to the rest of the world excluding China in the six months to May 2023 were worth nearly seven times their value in the six months to May 2020 when China announced its duties. Of course, as well as successful export redirection, the blow of China’s economic coercion has been massively cushioned by a range of fortuitous mitigating factors for barley exporters. These include, among others, a spike in food inflation globally, good growing conditions in Australia, and a related increase in the volume of overall Australian barley production. Still, the case of barley once again highlights the severe challenges China has faced in seeking to impose economic costs on Australia, while also showing how effectively (some) Australian exporters have been able to redirect to alternative markets.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

A sunny restatement of the case for Australia, but not so much for China's.

"The blow of China’s economic coercion," for example, did FAR less damage to Australia than the blow of Australia's economic coercion did to China.

"The case for getting these (in all likelihood) politically motivated duties removed" would be stronger if they were not so richly deserved.