Wine duties, export concentration, iron ore and lithium trade, and AI-enhanced analysis

Fortnight of 5 to 18 February 2024

Wine duties and a ministerial meeting

Minister for Trade and Tourism Don Farrell on the next step for the Albanese government if China doesn’t remove its duties on Australian wine next month:

“[W]e will immediately resume our World Trade Organisation dispute — and we’ve made that very clear to the Chinese authorities.”

Quick take:

The Australian wine industry is on tenterhooks at the prospect of a reprieve from China’s duties. One Australian winegrower said to ABC News earlier this month that the removal of these trade restrictions “could mean up to a 20 per cent increase in sales.” It’s not clear whether the mooted 26 February meeting between Minister Farrell and Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao will produce publicly telegraphed progress on that front. But regardless of Beijing’s long wine duties investigation timeline, which runs until 30 November this year, Canberra is adamant that it’ll restart dispute proceedings if these trade restrictions aren’t removed after the end of the suspension of the World Trade Organization (WTO) panel’s work on 31 March. Combined with China’s apparent desire to avoid a resumption of the WTO dispute proceedings, Canberra’s warning suggests that the Farrell-Wang meeting is likely to lay the groundwork for the removal of the duties by the end of next month. That said, the Global Times is still signalling that the “Australian side [should] remain patient” on the wine duties. But with even the nationalistic Chinese press platforming Australian wine industry optimism in the same article, it looks like the duties won’t last much longer.

Beyond avoiding the potentially embarrassing resumption of WTO dispute proceedings, Beijing has another reason to remove the wine duties. Failure to do so would work against China’s objective of pursuing a more ambitious cooperative agenda in the bilateral relationship. In particular, leaving these duties in place would make the kind of collaboration that China seems to want in the military and technology domains, among others, even less likely. Of course, this neither guarantees that Beijing will remove the duties on wine, much less that Canberra will be willing to embrace more cooperation if these trade restrictions are dismantled. But even if removing the wine duties won’t on its own get China the kind of bilateral relationship it wants, leaving them in place is a sure-fire way to further dampen enthusiasm in Canberra for extra collaboration with Beijing. So, while Chinese diplomats in Australia have been at pains to stress the opportunities to be gained from “continuously improving, maintaining and developing the relationship” (and in a similar vein here, here, and here), it’s hard to see how those bilateral prospects can be realised if the wine duties aren’t removed.

To be sure, the bilateral atmosphere has become gloomier following the 5 February announcement that the Australian writer Yang Hengjun had received a suspended death sentence. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and his ministers have expressed “outrage” and called the suspended death sentence “appalling” and “distressing,” while Beijing has sought to rebuff those Australian concerns. Australia’s full-court press on Yang’s case, which spans the Government, the Opposition, the parliamentary crossbench, Australian officials, and human rights groups, will continue regardless of what China does in relation to wine duties. But Beijing presumably understands that the more setbacks it imposes on Canberra, the more public and official incredulity it’s likely to encounter in Australia as it pushes for more bilateral cooperation. So, Beijing’s aspirations for bilateral ties likely provide an additional strong incentive to relent on wine duties.

Australia’s extra export concentration on China

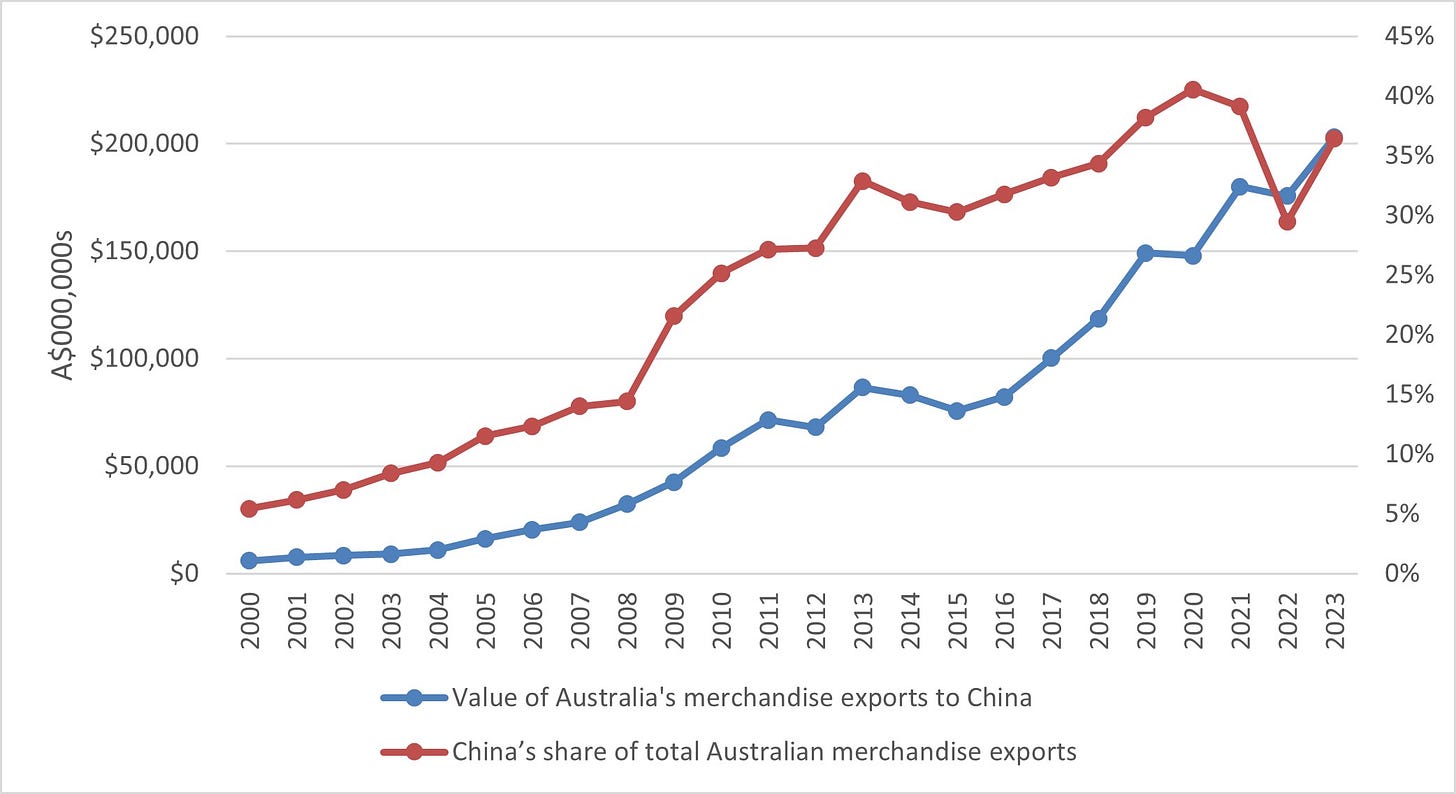

The value of Australia’s merchandise exports to China and China’s share of total Australian merchandise exports, 2000-23 (calculations based on data available here and here):

Quick take:

It’s unclear whether China will ever regain its 2020 peak of accounting for nearly 41% of Australian merchandise exports by value. Still, Australia’s goods export concentration on the Chinese market could easily increase beyond its 2023 level this year. After a dramatic dip to below 30% in 2022, the surge to 36% of Australia’s merchandise exports by value in 2023 occurred despite China’s ongoing trade restrictions against several Australian exports. No Australian barley was exported to China prior to August 2023, while last year’s alcohol (mostly wine) and copper ores and concentrates exports to China were only worth 3% and 6%, respectively, of their annual pre-economic coercion levels. So, assuming Beijing removes its wine duties and Chinese companies start purchasing Australian copper ores and concentrates at previous levels again, billions more dollars’ worth of these exports might head to China in 2024. Despite a rapid resumption of Australia’s coal trade with China from January 2023 onwards, the annual value of this export has still only risen to around 86% of its pre-economic coercion level, which also suggests that deeper merchandise export concentration on the Chinese market is possible this year.

Of course, the values of Australian commodity exports bounce around due to a wide range of factors. These include farming conditions in Australia, global food inflation rates, transportation costs, and international demand, among many others. This volatility means that China’s economic coercion ending entirely and the volumes of the impacted exports returning to pre-2020 levels won’t necessarily translate into rising Australian merchandise export values to China. Still, the likely ongoing removal of China’s trade restrictions and sustained high global prices for many Australian commodities mean there’s a good chance that both the value and the proportion of Australia’s merchandise exports going to China will continue to rise in 2024.

What does the rebound in Australia’s merchandise export concentration on the Chinese market in 2023, and potentially beyond, mean for the Australian government and businesses? Among other implications, it points to the challenges of trade diversification. Yes, many Australian exporters were able to successfully redirect to alternative markets in the wake of China’s trade restrictions. And yes, the Albanese government has continued Australia’s bipartisan tradition of expanding opportunities for Australian exporters with additional and upgraded trade agreements. Yet despite all that and other government measures, Australia’s aggregate merchandise export concentration on the Chinese market remains high, spiked in 2023, and could increase further this year. To be fair, the measure of success for Australia’s trade diversification agenda isn’t necessarily a deep and ongoing reduction of overall merchandise export concentration on the Chinese market. But even if some firms and perhaps even some industries have shifted some of their focus away from the Chinese market, the above data suggests that trade diversification at the macro level is swimming against a tide of deep and enduring economic complementarities between Australia and China.

Iron ore and lithium exports

The value of Australia’s iron ore and lithium exports to China, FY2006-07 to FY2022-23 (calculations based on data available here):

Quick take:

The value and proportion of Australia’s merchandise exports going to China in 2024 is likely to be strongly influenced by two key commodities: iron ore and lithium. During Beijing’s economic coercion campaign, the annual value of Australia’s exports of iron ore to China as a percentage of the value of its overall merchandise exports to China didn’t drop below 54% and reached a high of 74% in FY2020-21. Iron ore prices surged at the end of 2020 and the first half of 2021, which coincided with the expansion of China’s economic coercion campaign. So, despite acute pain for some Australian industries, the impact of China’s economic coercion on the overall value of exports to the Chinese market was cushioned by this spike in iron ore prices.

The fortunes both of government revenue at the state and federal levels and some of Australia’s largest companies will be shaped by iron ore demand in China and global prices, among other factors. But these iron ore trends will also heavily impact the total value of Australia’s goods exports to China, as well as the extent of Australia’s merchandise export concentration on the Chinese market. Given the troubles in the Chinese property market, the scale of provincial government debt, and China’s economic slowdown, it seems probable that Chinese demand will moderate further and the value of Australia’s iron ore exports to China will continue to slip in 2024, albeit from a stratospherically high level. This could easily contribute to a reduction in the value and proportion of Australia’s merchandise exports going to China this year.

Meanwhile, China’s imports of Australian lithium in the form of spodumene concentrate also jumped dramatically during China’s economic coercion campaign. From less than $1 billion worth of lithium exports to China in FY2020-21, Australia exported nearly $20 billion worth in FY2022-23. Lithium emerged as Australia’s third most lucrative merchandise export to China that financial year, accounting for approximately 10% of the overall value of goods exports to China. (For the trade data enthusiasts: Because the AHECC lithium concentrates classification 25309011 does not allow for partner country breakdowns in the DFAT pivot tables, the above graph and figures use exports to China of SITCr4 278 crude minerals, nes as a proxy for lithium concentrates. This seems broadly defensible for present purposes given that the differences between the values of exports of 278 crude minerals, nes to China and the true values of exports of 25309011 lithium concentrates to China are likely be modest. Using the proportion of Australian lithium concentrates going to China in the latest DISR Resources and Energy Quarterly, the FY2022-23 difference between the values of exports of 278 crude minerals, nes and 25309011 lithium concentrates to China was only circa $124 million compared to a total value of circa $20 billion .)

With nearly all Australia’s lithium exports going to China and the global price for this commodity still volatile, it could also contribute to a reduction in the value of Australia’s merchandise exports to the Chinese market. Considering the meteoric growth of China’s vertically integrated EV (electric vehicle), battery, and refining industries, Chinese demand for Australian lithium looks to be on a strong long-term growth trajectory. But if this commodity’s price continues its recent plunge, then the value of Australia’s lithium exports to China could drop significantly this year. Either way, the colossal profiles of commodities like iron ore and lithium in bilateral trade means that they will play a big role in determining the value and proportion of Australia’s merchandise exports going to China in 2024.

AI-powered Australia-China analysis

Since its inception, BCB has sought to gain a fuller understanding of the Australia-China relationship by analysing the dynamic and complex interplay between its many different parts. This analysis integrates a wide range of datapoints and trends that span the diplomatic, political, security, trade, investment, people-to-people, and other dimensions of bilateral ties. To extend this integrative approach and explore the prospects for the use of generative AI (artificial intelligence) to analyse the Australia-China relationship, BCB has teamed up with Dragonfly Thinking—a start-up coming out of the Australian National University (ANU).

The resulting report features cyborg analysis that combines generative AI and human insights to produce a systems map of the diverse drivers shaping the Australia-China relationship. Given the breadth and depth of the bilateral relationship, this systems map doesn’t cover everything. The contestable nature of much Australia-China analysis also means that many of these drivers will be open to debate and alternative interpretations. Still, this report hopefully gives a flavour of how generative AI can be harnessed to do integrative analysis of complex systems, including the Australia-China relationship.

This report was co-authored with the ANU’s Professor Anthea Roberts and Dragonfly Thinking’s RRR.ai application. RRR.ai is an interactive software that uses Anthea’s Risk, Reward, Resilience framework and which can be applied by users to any issue. You can see other examples of Dragonfly Thinking’s products here. And to learn more, you can contact the Dragonfly Thinking team here.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

Thank you for your note. I am unable to see the resulting report from Dragonfly Thinking. Is it possible for that to be shared by any chance?

But even if removing the wine duties won’t on its own get China the kind of bilateral relationship it wants, leaving them in place is a sure-fire way to further dampen enthusiasm in Canberra for extra collaboration with Beijing.?

If I were Beijing, I would want nothing to do with Australia.

We have treated China disgracefully since 1944 even as they treated us generously and honestly.

And our censorship of news about China is unaltered since the 1950s, when I first encountered it.

Beijing would be better off without us.