Wine exports, the latest on lobster, and one-China policies and principles

Weeks of 8 to 28 July 2024

Wine wins

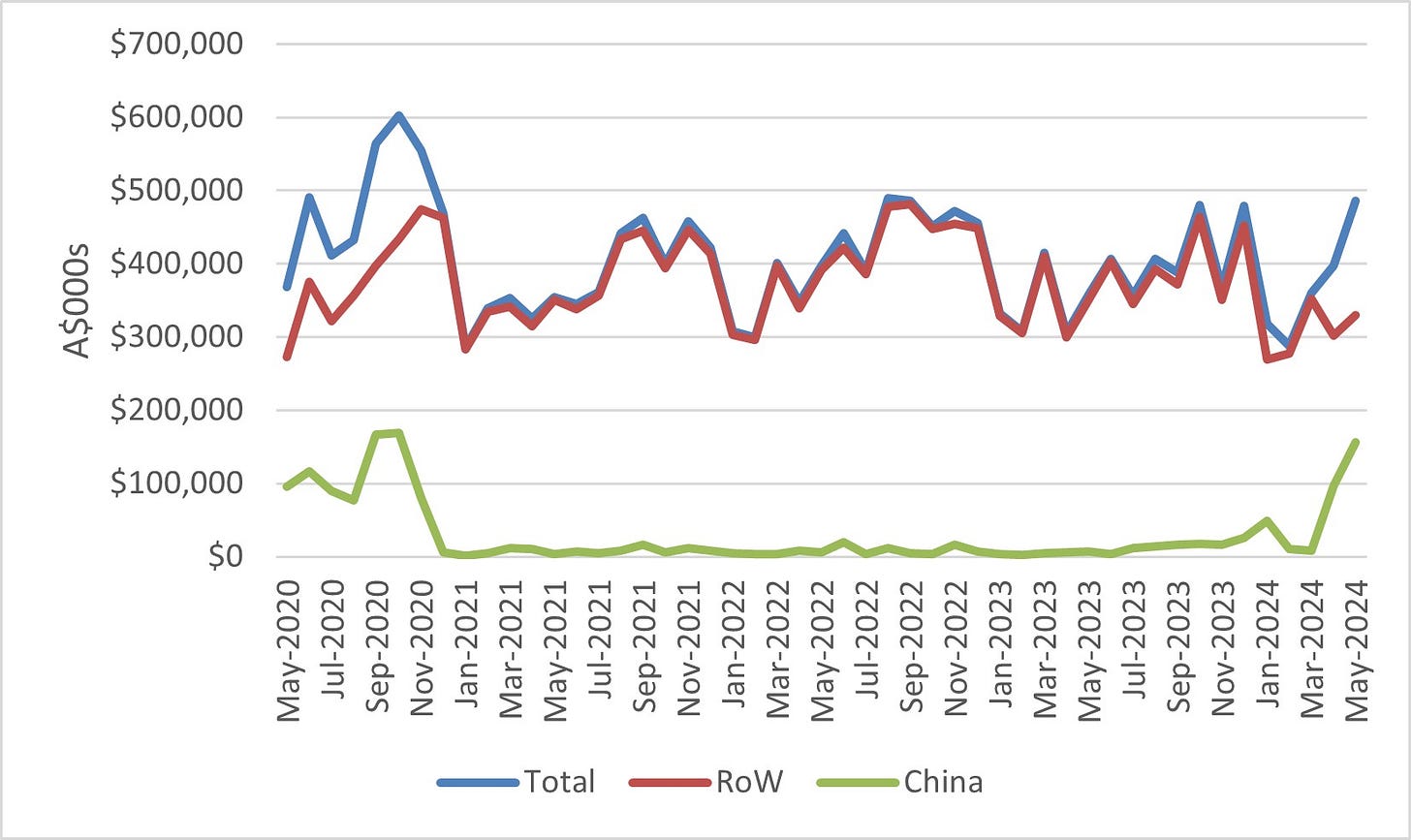

The monthly value of Australia’s alcoholic beverages exports (principally wine) to China, the rest of the world, and total, May 2020 to May 2024:

Quick take:

The Albanese government trumpeted these latest wine export figures. That’s unsurprising considering the size of the spike in this trade with China. The value of Australia’s alcoholic beverages exports to China in May 2024 was approximately seven times the average monthly value in the six months leading up to Beijing’s removal of its wine duties in March of this year. Zeroing in on a comparison of the month of May alone, the rise was even more dramatic. The value of Australia’s alcoholic beverages exports to China in May 2024 was more than 23 times the value at the same time last year. And Beijing’s removal of wine duties didn’t just impact the value of Australia’s alcoholic beverages exports to China. It also saw a big bounce in the topline figure of the overall value of this export. In fact, there was only one month since China’s imposition of duties on Australian wine in November 2020 that the total value of Australia’s alcoholic beverages exports surpassed the May 2024 number (and even then only by a few million dollars). The total value of this export in May 2024 was even a smidge above the average total monthly value of this export in the six months prior to China levelling duties.

Whether over the long term the value of Australia’s wine exports to China can maintain or even surpass the May 2024 number remains to be seen. It’s possible that the recent steep increase is at least partly a product of pent-up demand for Australian wine and that it won’t necessarily be sustained in the months and years ahead. China’s domestic economic headwinds and cost of living pressures, among other factors, might also dent the longer-term prospects for Australian wine in the Chinese market. Still, the sheer size of the upsurge in the value of Australian wine exports to China following the removal of Beijing’s duties again underscores the power of the market forces driving bilateral economic interdependence. The Australian public might still be deeply distrustful of the Chinese government, Canberra might still be talking about the case for trade diversification, and Australia’s corporate leaders might still be warning about the risks of putting too many “eggs in the China basket.” And yet the Australian wine industry’s recent experience provides another example of how quickly the bilateral economic embrace can tighten once trade restrictions are removed.

Live lobster languishes

The then Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry Murray Watt speaking to Sky News on 18 June:

“[N]othing really compares with the premium, particularly in lobster, that China provides. So we’re very hopeful that as a result of this visit [by Chinese Premier Li Qiang], that we will see those remaining suspensions lifted soon.”

Quick take:

Despite the recent positivity about wine (above) and beef (here and here), Canberra’s ballooning optimism in June about live lobster exports has since deflated somewhat. Having repeatedly and enthusiastically talked up in June the likelihood of China removing these trade restrictions, live lobster exports seem to have largely dropped from the Albanese government’s public talking points in recent weeks. In a speech on 17 July, Minister Watt highlighted China’s outstanding trade restrictions on two red meat exporters and celebrated the removal of other trade restrictions. And yet he made no mention of the biggest and most painful of the remaining trade restrictions against live lobster.

It’s hard to know precisely what the Albanese government’s winding back of public comment on China’s trade restrictions on live lobster means. Is it simply an exercise in discretion as Australian and Chinese officials enter the final and potentially sensitive stages of a negotiated settlement? Or is there likely to be a longer delay for the removal of these trade restrictions because Beijing is trying to extract some extra concessions from Canberra before letting live lobster back in unimpeded? And has the Albanese government accordingly decided to stop drawing attention to these enduring trade restrictions because it now knows that they’ll be in place for longer?

These publicly unanswered questions notwithstanding, the removal of China’s trade restrictions on live lobster seems delayed rather than indefinitely on ice. Among other factors, the domestic political importance for the Albanese government of getting the trade restrictions removed and China’s desire to expand and deepen bilateral ties mean that both Canberra and Beijing have strong incentives for reopening formal paths for Australian live lobster to re-enter the Chinese market. Although the removal of these trade restrictions isn’t guaranteed, it still seems likely, albeit on a more extended timeline than the Albanese government previously predicted.

Debating one-China policies and principles

The then Secretary of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs, Keith Waller, writing in a Secret Minute to Prime Minister Gough Whitlam on 13 December 1972:

“[W]e could always arrange … for it to be brought to the attention of the press in an unattributable background briefing that our Taiwan paragraph had not gone as far as the Maldives ‘recognises that Taiwan is an inalienable part of the territory of the PRC’.”

Quick take:

As I wrote in the last edition of BCB, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) appears determined to spread the falsehood that Australia is bound by the one-China principle, according to which, among other things, “Taiwan is an inalienable part of China.” Taking issue with my criticisms of what I assess to be a campaign of Chinese government disinformation, Jocelyn Chey has since responded by claiming that Canberra is in fact committed to the one-China principle. Writing in a piece published on 22 July, she argues:

“Principle surely underpins policy. How could government policies contradict principles? The Joint Communique refers to principles and acknowledges/recognises/agrees ‘that Taiwan is a province of the [PRC]’. Policies have been developed since from that foundation.”

Chey’s characterisation of the Australian government’s position is questionable on at least two key points. First, her assertion that the 1972 Australia-China Joint Communique “acknowledges/recognises/agrees ‘that Taiwan is a province of the [PRC]’” is simply incorrect. Instead, the Australian government in the Joint Communique “acknowledges the position of the Chinese Government that Taiwan is a province of the [PRC]” (emphasis added). Regardless of the discrepancy between the dual use of the verb “承认” in the Chinese-language version and the contrasting uses of “recognises” and “acknowledges” in the English-language version, neither version of the crucial third paragraph of the Joint Communique includes, as Chey misleadingly renders it, a direct Australian acknowledgement or recognition that “Taiwan is a province of the [PRC].” Given the formula of instead acknowledging “the position of the Chinese Government,” it’s plausible to interpret Canberra as saying that it observes that Beijing holds the position that Taiwan is a province of the PRC without also endorsing the substance of this position itself (i.e., without also endorsing the view that Taiwan is in fact a province of the PRC). On this reading, the acknowledgment in the Joint Communique has one of the commonplace and accepted meanings of acknowledges, namely, recognising the existence of something (i.e., Australia recognises the existence of the Chinese government’s position on Taiwan).

In addition to the Minute to Prime Minister Whitlam quoted above, Canberra’s view that it had acknowledged without endorsing the PRC’s position is emphasised in other since-declassified Australian government documents. These include a cable to Australia’s diplomatic posts a day before the Joint Communique was publicly issued specifying that Canberra “stood out against the wording suggested by China” and insisting that the Australian language “is very similar to” taking note of the PRC’s position on Taiwan. To be sure, Australia’s acknowledgement of the PRC’s position is likely not as clear a non-endorsement of the one-China principle as Canada’s formulation of merely taking note. But even so, nowhere in the Joint Communique does Australia affirm the one-China principle and Australian officials at the time were at pains to stress that the meaning of Canberra’s acknowledgement of Beijing’s position fell short of such an endorsement. So, even if one concludes that Australia’s acknowledgement of the PRC’s position on Taiwan is ambiguous and open to multiple plausible interpretations, it still doesn’t amount to an endorsement of the one-China principle.

This leads to the second key concern with Chey’s characterisation. She argues that “[p]rinciple surely underpins policy” and that “even if stated obliquely, the Joint Communique refers to a ‘One China principle,’ not a ‘One China policy’.” Certainly, policies are often underpinned or guided by principles. And Australia’s one-China policy as implemented over the course of more than five decades has been guided by, among others, some of the principles articulated in the Joint Communique. But these principles are not necessarily the same as Beijing’s one-China principle. Yes, the Joint Communique commits Australia to pursuing policies that accord with, for example, the principle that the PRC is the “sole legal Government of China.” But neither that principle, nor any other principles to which Australia committed itself in the Joint Communique, are the same as Beijing’s one-China principle. Policies might well be built on principles, but the Joint Communique and associated primary source documents suggest that Beijing’s one-China principle isn’t among those guiding Australia’s one-China policy.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

China’s domestic economic headwinds and cost of living pressures, among other factors, might also dent the longer-term prospects?

China's economy is growing faster than in all but three previous years and inflation is 1%.