Trade disputes dissipate, Canberra's tactical caution, and leader-level meetings

Fortnight of 3 to 16 April 2023

Trade disputes dissipate

Communication on 13 April from the Chairperson of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Panel on dispute settlement case 598 (“China — Anti-dumping and countervailing duty measures on barley from Australia”):

“On 11 April 2023, the parties requested the Panel to suspend its work, in accordance with Article 12.12 of the DSU [Dispute Settlement Understanding], until 11 July 2023. The Panel has agreed to this request.”

Quick take:

This development opens up what Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong has described as a “pathway” for a resolution of the dispute over China’s anti-dumping and countervailing duty measures against Australian barley. Although these trade measures have not yet been removed and Canberra reserves the right to resume the dispute via the WTO if they are not lifted, it seems likely that the apparently “expedited review” by the Chinese government will result in their removal in the coming months. And assuming this removal goes to plan, it also seems probable that China’s anti-dumping and countervailing duty measures against Australian wine will be similarly dismantled later this year. As Minister for Foreign Affairs Wong put it on 11 April: “[T]he Australian Government would expect a similar process to be followed in relation to the trade barriers which exist on Australian wine.”

What does all this mean for the slowly loosening grip of China’s economic coercion against Australia? As I’ve previously argued, a continued progressive dismantling of China’s trade restrictions in the coming months looks most likely. Informal restrictions on coal and cotton appear to be subsiding, while technical barriers on beef, timber, and crustaceans also look set to fall away. Given the face-saving offramp that Australia is offering China in relation to what would possibly/probably have been adverse findings on anti-dumping and countervailing duties against barley and wine, Beijing will presumably be willing to remove these measures in the coming months as well. Such a dismantling of the full suite (or close to) of China’s trade restrictions seems especially likely considering the combination of the still remarkably upbeat tenor of China’s Australia diplomacy and the positive Chinese government signals for Australian wine and barley exporters.

I’ll leave it to the trade lawyers and economists to debate the rights and wrongs of these potentially directly negotiated settlements of the disputes over China’s barley and wine measures. Are these the kinds of direct and efficient negotiated resolutions that one would expect (or at least hope) WTO structures and procedures to facilitate? Or should Australia have proceeded with these disputes to impose additional reputational costs on China for its economic coercion? (For what it’s worth, I tend to think this direct negotiation route was the right call given that Canberra’s regularly repeated concerns about economic coercion had already imposed significant reputational costs on Beijing. Moreover, it seems entirely possible that China would have made direct negotiations a precondition for the removal of the measures against barley and wine, meaning that these measures could have been in place for much longer/potentially indefinitely if Australia hadn’t been willing to suspend WTO dispute settlement proceedings. Of course, these are speculative points, and I fully accept that others will legitimately see the potentially directly negotiated settlements as strategically questionable.) In any case, and regardless of one’s view of the wisdom/lack thereof of Canberra’s decision, it seems that Australia’s barley and wine exports have a good chance of more freely flowing into China again later this year.

Yet even if unblocked trade flows eventuate, it doesn’t mean that barley, wine, and other previously restricted Australian exports will be getting back into China at the same value and volume as before Beijing’s campaign of economic coercion kicked off in May 2020. The market disruptions endured these past few years will take time to unwind, and some of Australia’s redirected exports might not return (or at least not at past levels) to the Chinese market for commercial and risk-management reasons. But even if the value and volume of previously restricted Australian exports don’t return to their pre-2020 levels, I’d expect that most, if not all, of China’s trade restrictions will have been removed by the second half of 2023. Perhaps just in time for Prime Minster Anthony Albanese’s long-mooted and recently rumoured trip to Beijing sometime around October?

Canberra’s tactical caution and the (positive) Australia-China trade outlook

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Wang Wenbin responding on 11 April to a question about the agreement between Canberra and Beijing on the WTO barley dispute:

“By following the principles of mutual respect, mutual benefit and seeking common ground while shelving differences, we aim to reestablish trust between the two countries and bring bilateral relations to the right track and, in this process, resolve our respective concerns on trade and economic issues in a balanced way through constructive consultation to the benefit of both peoples.”

Quick take:

My above prediction of a progressive relaxing of China’s trade restrictions could, of course, prove wrong. Notwithstanding all the positive bilateral signals from both Canberra and Beijing, there’s always the possibility of flareups in Australia-China ties or at least roadblocks to ongoing relationship repair. Although China’s reaction to Australia’s ban on TikTok on government-issued devices was fairly boilerplate and understated, other possible sources of tension remain. If Australia definitively tears up Chinese company Landbridge Group’s 99-year lease of Darwin Port or slaps sanctions on Chinese officials and entities implicated in severe human rights abuses in Xinjiang, then China might reconsider its progressive unwinding of trade restrictions. Meanwhile, if China decides to not remove its anti-dumping and countervailing duties on barley and wine, then Australia is likely to resume its WTO dispute settlement proceedings. (I hope it goes without saying that I’m not suggesting that there’s a moral equivalence between these possible actions and/or reactions. The point is just to highlight the range of developments that might again destabilise relations between Canberra and Beijing.)

But given what we’ve observed in the nearly 11 months of the Albanese government, Canberra seems unlikely to take the kinds of decisions that would significantly disrupt ongoing relationship repair. Prime Minister Albanese is seemingly committed to stabilising and repairing the Australia-China relationship as part of his first-term legacy. Accordingly, his government has made a series to tactical manoeuvres to tamp down the likelihood of bilateral relationship fallout from Canberra’s hard China policy dilemmas. The Albanese government has, among other things: eschewed the use of targeted sanctions against Chinese officials and entities implicated in severe human rights abuses; decided not to veto Confucius Institutes at Australian universities and instead continue scrutinising them; and seemingly sought to time the rejection of one Chinese investment to coincide with the approval of another Chinese investment. Meanwhile, the Albanese government has (largely) stuck to its warmer talking points for describing the Australia-China relationship.

To be sure, Canberra still takes positions that can plausibly be construed as broadly “tough on China.” These include, among others, steaming ahead with the acquisition of nuclear-powered AUKUS submarines, removing Chinese-manufactured intercoms and surveillance equipment from government buildings, and restricting the Chinese-owned app TikTok from government-issued devices. But these positions were either substantively taken by the previous government and largely baked into bilateral ties (e.g., AUKUS submarines) or unlikely to seriously upset Beijing because of their limited scope (e.g., the TikTok and intercoms/surveillance equipment decisions, which only impacted a comparatively small number of government devices and buildings). So, overall, I don’t see any strong data points suggesting a deviation from the Albanese government’s tactical caution on China.

Of course, this isn’t to say that the Albanese government is now free of any hard China policy dilemmas. But I’d also expect Canberra to generally take a tactically cautious approach to issues like the ongoing Darwin Port review, future Chinese investment decisions, and the competing Chinese and Taiwanese bids for entry into the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). This tactically cautious approach will likely be aimed at threading the needle of maintaining tough-ish positions on China while also minimising the upset caused in Beijing. What does such tactical caution look like in practice, you might fairly ask? Here’s my take on how it has played out in relation to Confucius Institutes and Chinese investments, together with how it might be operationalised in the case of the Darwin Port review. As ever, please don’t hesitate to object and/or correct if you think I’m off the money in any of these cases. And I freely admit that my account of the Albanese government’s tactical caution on China is a working assessment that’s very much liable to revision.

Yet even if, as I’m predicting, Canberra exercises tactical caution on China, it’s still possible that Beijing will play a spoiler role. Beijing might decide to keep its anti-dumping and countervailing duties on Australian barley and wine in place regardless of Canberra finessing its China policy choices to avoid aggravating the Chinese government. Beijing might also decide to slow roll or even stall the removal of other trade restrictions even if Canberra cleaves to a tactically cautious China policy path. Such scenarios are certainly possible. But all the exceedingly positive signals emanating from the Chinese government make them unlikely in my view. And given that Beijing seems to have taken a decision at a high political level to repair the Australia-China relationship, it’d likely complicate the Chinese government’s own objective to not take advantage of the opportunity to continue to unwind measures against Australian barley, wine, and other targeted exports.

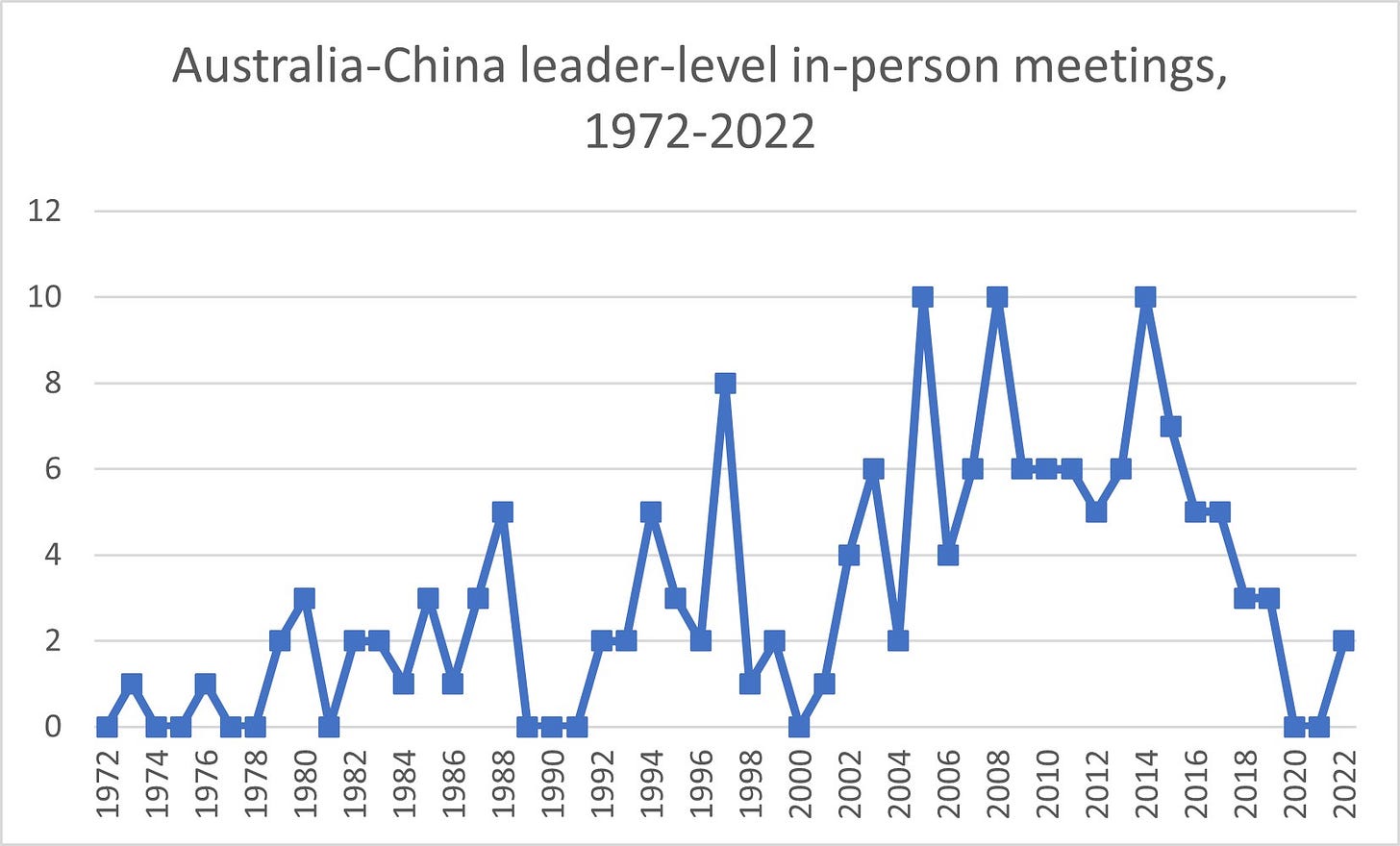

Updated leader-level meetings since 1972

The number of face-to-face meetings between Australian prime ministers and governor-generals and Chinese leaders and senior officials, December 1972 to December 2022:

Quick take:

Here are a couple of observations based on this updated version of a graph that I’ve previously published:

The recent period without face-to-face meetings at the leader level between November 2019 and November 2022 was the longest absence of in-person contact between Australian prime ministers and governor-generals and Chinese leaders and senior officials since 1989-91. In particular, it was the most sustained such hiatus since the more than three-year gap between Premier Li Peng’s Australia visit in November 1988 and Vice Premier Zhu Rongji’s visit in February 1992. (Unless I’m missing something?) The recent hiatus is especially striking considering that Australian prime ministers and governor-generals met in person with Chinese leaders and senior officials on average more than six times each year in the ten-year period 2006-15.

Even in the 1970s and 1980s—when face-to-face meetings between Australian leaders and their Chinese counterparts were much less frequent—the longest period without such an engagement was the period April 1973 to June 1976. Leaving aside the post-Tiananmen Square Massacre collapse in leader-level meetings, this means that one would need to go back to the very earliest years of the Australia-China diplomatic relationship to find a longer gap in face-to-face meetings at the leader level. This also means that there have only been two gaps in face-to-face leader-level engagement longer than the recent curtailment: 1973-76 and 1989-91.

For reference, the database on which the above graph is based might still be missing some face-to-face meetings between Australian prime ministers and governor-generals and Chinese leaders and senior officials. As I’ve written previously, this is especially likely to be true of the first decade or so of the diplomatic relationship. The absence of any in-person meetings in the year 2000 also appears odd in the context of at minimum one meeting per annum every other year from 1992 onwards. The year 2000 is all the more conspicuous considering that on average three such meetings occurred each year in the five years before 2000 and on average five such meetings occurred each year in the five years after 2000. Please send through any corrections or additions that you might have on this or any other years.

As a final caveat, it’s worth noting that the vast majority of the Chinese leaders and senior officials captured in the above dataset are Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials at the level of Politburo or above or Chinese government officials at the level of Minister or above. In a small number of cases, the data includes meetings with senior Chinese representatives who did not hold CCP or Chinese government positions at those ranks (e.g., former Vice Premier Gu Mu’s meetings in 1987 with Prime Minister Bob Hawke and Governor-General Ninian Stephen). Although the inclusion of these meetings can certainly be debated given that they might not carry the same import as a true leader-level meeting, I err on the side of adding them given the participation of the Australian Prime Minister/Governor-General.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

"The Albanese government has, among other things: eschewed the use of targeted sanctions against Chinese officials and entities implicated in severe human rights abuses; decided not to veto Confucius Institutes at Australian universities " ........so, trade sanctions, slowly appearing like they might be removed, are working. The partial loss of Australian freedom of speech resulting from CCP control of all Chinese language media and social media, and its censorship and narrative control of Youtube competitor TikTok, urgently requires a solution as well (ban / control / accept colonial status), but currently, our ability to make sovereign decisions is curtailed by the carrot of maybe reinstating normal trade. This appears to be this governments status quo. I was born in a free country, and now we are reduced to this....

"Given the face-saving offramp that Australia is offering China in relation to what would possibly/probably have been adverse findings on anti-dumping and countervailing duties against barley and wine, Beijing will presumably be willing to remove these measures in the coming months as well."??

China, based on past form, would probably have prevailed in the WTO in both cases. Some Australian exporters, for whatever reasons, have abused their access, falsified paperwork, and shipped feed grade grains as food grade.

I suspect that China will stretch out the trade resumption process as Washington raises pressure on Canberra to destroy its main trading relationship.

It will be fun to watch, if nothing else!