A cornucopia of Australia-China disputes, parting ways on the Pacific, and the latest trade data

Fortnight of 3 to 16 October 2022

A smorgasbord of disagreements

China’s ambassador to Australia Xiao Qian quoted in The Sydney Morning Herald on 13 October:

“Even if we have differences or disputes, we should meet to talk and discuss and try to narrow down the differences and try to find a solution to those problems.”

Quick take:

As I’ve regularly emphasised, bilateral ties are beset by a broad range of deep-seated and longstanding substantive policy disputes. Notwithstanding Beijing’s shifting tone on Canberra since circa December 2021, the two are still at loggerheads on a wide range of issues from China’s legally untenable maritime claims in the South China Sea to the role of security considerations in Australia’s investment review procedures. Not only is the list of disagreements long, but it’s getting longer. The Albanese government might have started using less invective to talk about China, but disputes over the AUKUS security partnership and China’s security role in the Pacific (among others) continue to intensify.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Ambassador Xiao sounded some frustrated notes in his recent interview, saying that “[i]t seems we’re not moving fast enough, not as fast as China would expect.” But he and his government really shouldn’t be shocked. Considering the many longstanding points of deep disagreement and the new areas of dispute, any plans for a relationship reset—much less a quick and easy one—were always unrealistic. This is especially true considering that Ambassador Xiao cited tensions over Taiwan and the treatment of Muslims in Xinjiang as barriers to an improved relationship. Given that these issues relate to fundamental moral and political considerations, including respect for human rights, the preservation of regional security, and the protection of liberal democracy, Australia and China were never going to “move towards each other,” to use the Ambassador’s words.

In a bid to empirically baseline gloomy bilateral analysis like the above, I thought it might be useful to start building a record of all the key areas of substantive policy disagreement between Australia and China. In what follows, I’ve separated the areas of dispute by thematic/policy arenas and tried to make a qualitative assessment of whether the disagreement is intensifying or subsiding. (It’ll come as no surprise that very few contentious issues are in the latter category.) I’ve also added some warnings and indicators of the kinds of developments that could cause tensions to significantly intensify.

Of course, these qualitative assessments (along with the framing of some of the disputes) are by their nature debatable, and I don’t for a moment claim that what I’ve suggested below is definitive. Although the below hopefully captures the most significant bilateral disputes, it’s equally not necessarily a complete list. If you think anything major is missing from the below or if any of the qualitative assessments really miss the mark, please flick me a note. I’ll aim to update what follows on a rolling basis depending on bilateral developments. I’ll also post a version of the below here on BCB’s companion website.

Human rights and Hong Kong

Intensity of disputes generally high but steady

Possible triggers for an increase in intensity:

Australia levelling targeted sanctions against Chinese officials in response to human rights abuses in Xinjiang

A further deterioration of human rights conditions in China and/or Hong Kong or new revelations of past human rights abuses

Key points of dispute:

China’s human rights abuses against ethnic and religious minorities and Australia’s public criticisms of the Chinese government’s policies (e.g., this)

China’s abrogation of Hong Kong’s rights and freedoms and the heavy-handed use of martial force in the Special Administrative Region and Australia’s public criticisms of these Chinese and Hong Kong government policies (e.g., this)

China’s suppression of freedom of speech and other fundamental human rights and Australia’s public criticisms of these policies (e.g., this and this)

Longstanding regional security disputes

Intensity of disputes generally high but steady

Possible triggers for an increase in intensity:

An Australian Defence Force (ADF) aircraft or vessel transiting within 12 nautical miles of a Chinese-claimed feature in the South China Sea

The evolution of the Quad to include branded joint military exercises

Key points of dispute:

Australia’s strong opposition to China’s legally untenable maritime claims in the South China Sea (e.g., this and this)

Deepening exchange and cooperation among Quad countries on a range of political, diplomatic, economic, cyber, infrastructure, and maritime fronts (e.g., this)

China’s growing military, diplomatic, economic, and related efforts to isolate and intimidate Taiwan and Australia’s support for the cross-Strait status quo (e.g., this)

New regional security disputes

Intensity of disputes generally high and increasing

Possible triggers for a further increase in intensity:

The operationalisation of the China-Solomon Islands security agreement to facilitate a People’s Liberation Army Navy port visit to Solomon Islands

Increasingly explicit statements from the Australian government that AUKUS submarines are intended to deliver a deterrent effect in North Asia, including in the Taiwan Strait

Key points of dispute:

Cooperation between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States to provide the Royal Australian Navy with nuclear-powered submarines as part of the AUKUS security partnership (e.g., this and this)

The China-Solomon Islands security agreement and deepening security cooperation between Honiara and Beijing (e.g., this)

China’s ambition to play an active security role in the Pacific and Australia’s view that Pacific security is a matter for the region (e.g., this)

National security

Intensity of disputes generally high but steady

Possible triggers for an increase in intensity:

The Minister for Foreign Affairs using Foreign Relations Act 2020 (FRA) powers to render invalid and unenforceable agreements establishing Confucius Institutes at Australian universities

Additional large-scale Chinese state or state-affiliated cyberattacks against significant Australian institutions and a formal and public Australian government attribution in response

Key points of dispute:

Australian legislation and policies to combat foreign interference in its politics and society, including counterintelligence and transparency measures (e.g., this and this)

The introduction of Australia’s FRA and the associated Foreign Arrangements Scheme combined with the Australian federal government’s subsequent use of FRA powers to render invalid and unenforceable Victoria’s Belt and Road Initiative agreements (e.g., this, this, and this)

Chinese state and state-affiliated cyberattacks against Australian companies, universities, and government institutions and the Australian government’s growing willingness to attribute these attacks to China and its proxies (e.g., this)

Consular cases and border control

Intensity of disputes generally moderate and steady

Possible triggers for an increase in intensity:

China detaining additional Australian citizens

New Australian investigations of and visa restrictions against Chinese nationals on espionage or foreign interference grounds

Key points of dispute:

The ongoing detention of Cheng Lei, Yang Hengjun, and other Australians (e.g., this and this)

The questioning of Chinese journalists in Australia and the intimidation of Australian journalists in China in 2020 (e.g., this and this)

The cancelation of Chinese scholars’ visas on security grounds in 2020 (e.g., this)

Economic statecraft

Intensity of disputes generally high but steady

Possible triggers for an increase in intensity:

Rejection of a large Chinese investment by the Australian Treasurer or Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB)

An adverse finding in the review of the 99-year lease by the Chinese company Landbridge of Darwin Port

Key points of dispute:

Adverse ministerial and FIRB decisions regarding investments from Chinese companies (e.g., this)

The growing role of national security considerations in Australia’s evaluation of foreign investments (e.g., this)

The exclusion of Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE as vendors for the construction of Australia’s 5G network in 2018 and the earlier exclusion of Huawei from National Broadband Network tenders (e.g., this)

COVID-19

Intensity of disputes generally moderate and slowly declining

Possible triggers for an increase in intensity:

Currently seems unlikely given the time elapsed since the global COVID-19 outbreak

Key points of dispute:

Pointed Pacific messaging

Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong speaking at a press conference in New York on 24 September:

“We have simply made the point, and as have other members of the Pacific Islands Forum, that we believe security is the responsibility of the Pacific family. And that is Australia’s position.”

Quick take:

Among the long list of disputes between Canberra and Beijing, China’s security role in the Pacific is among the newest points of intense contention. Driven by the news earlier this year of a security agreement between Solomon Islands and China, Australia has taken to regularly reiterating that it thinks the Pacific should take care of its own security. To be sure, Minister Wong hasn’t repeated this point every time China’s security role in the Pacific has come up (e.g., here). But both the Minister for Foreign Affairs and her junior portfolio colleagues (e.g., here and here) have repeatedly stressed the same general point. Earlier this year Minister Wong was even more direct when she raised concerns about “outside” powers being involved in Pacific security and said that regional “security is best provided by the Pacific family, of which we [Australia] are a part.”

What is Canberra hoping to achieve by seeking to deny China (by implication at least) a legitimate security role in the Pacific? If it wasn’t already clear to Beijing, this kind of messaging puts the Chinese government on notice that Australia doesn’t welcome its involvement in Pacific security initiatives. This kind of messaging equally signals to Pacific countries that not only does Australia seek to be their “security partner of choice,” but it also doesn’t want regional states to see extra-regional powers (and specifically China) as prospective security partners. So, the Australian government’s declarative policy can plausibly be seen as a twofold effort to dissuade both Beijing from involving itself in regional security and Pacific countries from engaging in security cooperation with China.

Added to these international considerations, there may also be a domestic rationale. In the wake of the Morrison government’s widely debated and criticised inability to forestall the China-Solomon Islands security agreement, the Albanese government might judge that there’s political advantage to be gained by taking a tough stance against China’s security role in the Pacific. Although China cooperating with Pacific countries on security obviously doesn’t necessarily entail the establishment of a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) base in Solomon Islands, Lowy polling on that latter issue seems to suggest that the Albanese government would be on solid public opinion ground when raising concerns about China’s security role in the Pacific. Some 88% of Australians said they were very or somewhat concerned “about China potentially opening a military base in a Pacific Island country.” It wouldn’t be much of stretch to infer from this that messaging aimed at warning China off playing a security role in the region is likely to be electorally popular.

The above considerations raise the first order policy question of whether Australia’s goal should be to stop China from playing a security role in the Pacific. Though a critical question, I won’t try and answer it in a few hundred words. But short of that, I’ll at least venture a (very) preliminary assessment of why the Australian government’s messaging might be counterproductive. As well as adding yet another irritant to the Australia-China relationship, Canberra’s opposition to outside powers (and especially Beijing) playing a regional security role seems highly unlikely to persuade China to give up its big Pacific ambitions. Notwithstanding China’s expressions of apparent deference to the “historical and traditional ties between Australia and the Pacific island countries,” it would be optimistic (maybe even wildly so?) to imagine that Beijing will moderate its long-term goals in the region because of Canberra’s concerns.

Perhaps more importantly though, it seems unlikely to persuade at least some Pacific countries. With news that Royal Solomon Islands Police Force have flown to China for training, it’s clear that Honiara at least is not averse to China making a security contribution to the Pacific. Meanwhile, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, and Tonga have previously received military equipment from China and the PLA hospital ship Peace Ark has periodically visited the Pacific. These and similar datapoints suggest another possible pitfall for the Albanese government’s messaging: The risk of long-term diplomatic embarrassment for Australia. It’ll arguably make Australian foreign policy look ineffective if Canberra’s calls for outside powers to not be involved in regional security are met with China’s deeper security engagement (at least in some parts of the Pacific).

Then there’s also the seemingly small but still important apparent gap between the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) and Australian positions on the issue of outside powers and security. In July this year, the PIF leaders reaffirmed “the concept of regionalism and a family first approach to peace and security.” Although similar, a “family first approach” doesn’t imply, as Australia’s messaging sometimes does, that outside powers shouldn’t be involved in Pacific security. The implication of the PIF language seems to be (at least as I read it) that if outside powers are involved, it should be after regional security options are exhausted. Now, of course, it’s perfectly legitimate for Canberra to adopt different positions to the PIF on a wide range of issues (as it obviously often does). But it perhaps sits awkwardly with Australia’s emphasises on Pacific cooperation when Canberra takes a different view on a question as core to the PIF as regional security. (To be sure, I’m not a PIF expert, so please correct me if I’ve missed some important nuance or datapoints on this issue.)

Assuming the above is right, what should Canberra be saying? Perhaps the simplest solution is to ditch the idea that Pacific security should exclusively be handled by regional countries and opt for the more inclusive PIF language of a “family first approach to peace and security”. This less exclusive framing was used by the Prime Minister’s Office in the short read out of Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare’s visit to Australia earlier this month. Such a less exclusive framing would put Australia firmly on the same ground as its Pacific partners and probably wouldn’t make it any more likely that China will deepen its security engagement with the region.

We’re admittedly well and truly deep in the linguistic weeds here and all the above points are, I freely admit, totally contestable. Taking a tough diplomatic line against any security role in the Pacific for China might still be judged to be the most prudent position for Australia, especially considering the long-term potential for an expansion of China’s regional security presence to deeply impact Australia’s own security. Still, it seems that the message that outside powers shouldn’t be involved in Pacific security is unlikely to offer an appealing balance of costs and benefits for Australia. A PIF-style Pacific first message might be more realistic and less likely to alienate Pacific partners, while also not impacting China’s approach.

August trade data

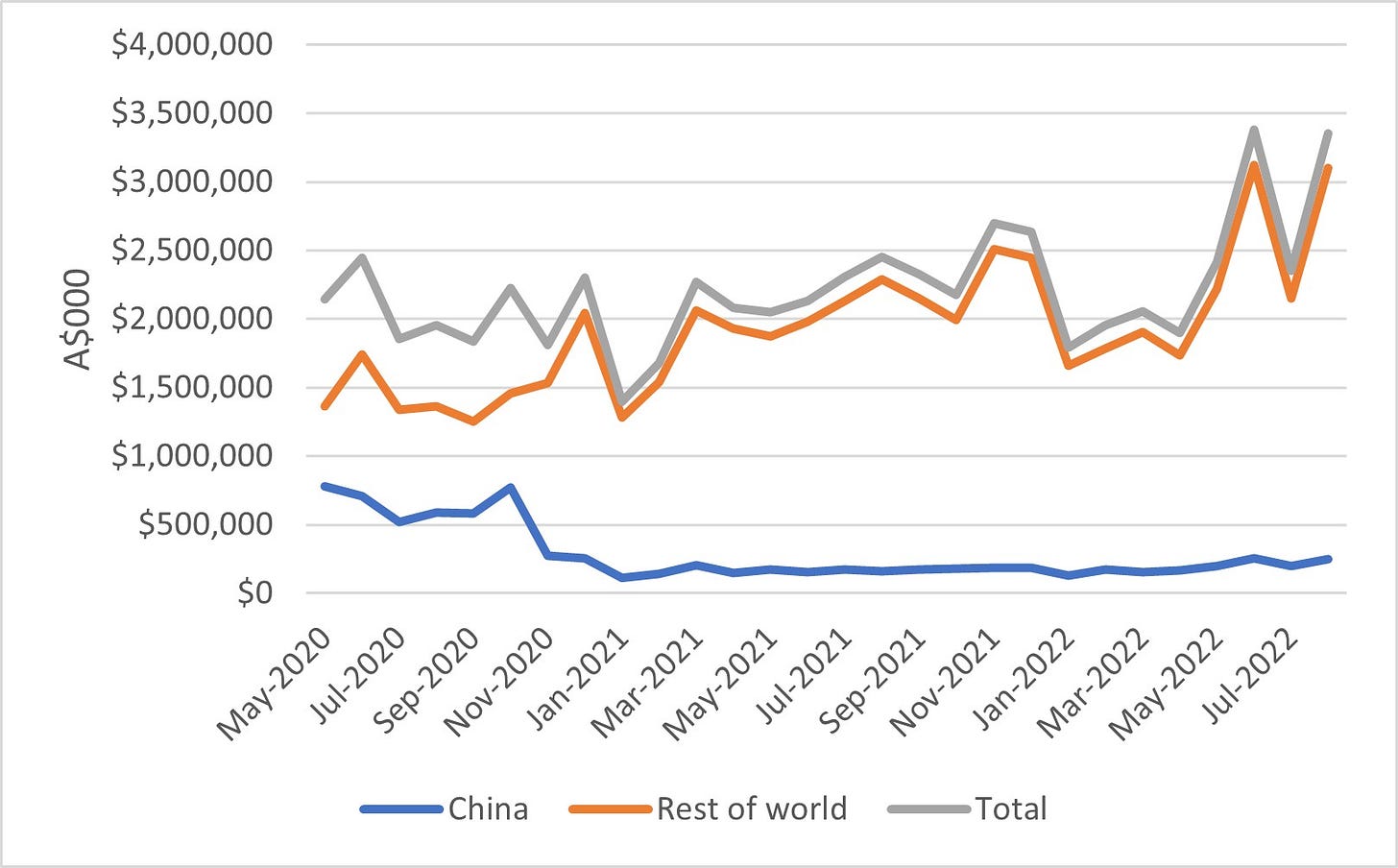

Based on the latest trade data, the combined monthly value of Australia’s nine exports targeted by China’s trade restrictions (to China, the rest of the world, and total, May 2020 to August 2022):

Quick take:

Despite the value of these nine exports to China now sitting at approximately 11% of their value in May 2020 when trade restrictions were first introduced, their value to the rest of the world is now roughly 400% of their value two-and-a-bit years ago. These numbers no doubt reflect diverse factors such as favourable growing conditions for a range of Australian agricultural exporters and high food prices globally. But most importantly, these numbers are a result of the combination of the disproportionate value of coal exports in this basket of nine exports and the rapid and sustained rise in coal prices since 2020. Coal exports accounted for roughly 77% of the overall value of these nine exports as at August 2022, while coal prices have seen something in the order of a fivefold increase since late 2020.

At the same time though, these numbers also probably reflect the ongoing and generally successful redirection of the Australian exports that have been in some cases totally shut out of the Chinese market. The below graph charts the combined monthly value of the eight Australian exports excluding coal that have been targeted by China’s trade restrictions (to China, the rest of the world, and total, May 2020 to August 2022). Despite the value of these eight exports to China now sitting at approximately 32% of their value in May 2020 when trade restrictions were first introduced, their value to the rest of the world is now roughly 228% of their value two-and-a-bit years ago. This increase in the monthly value of these exports has occurred despite some of these exports, including copper ores and concentrates and barley, being entirely excluded from the Chinese market.

Of course, some Australian exporters have endured much more pain than others. As Minister for Trade and Tourism Don Farrell remarked on 11 October in relation to Australia’s lobster industry: “I’ve had some chats with the South Australian lobster exporters, and what they tell me is the prices they’re getting in Australia for their product in many cases don’t actually cover the cost of production.” And Minister Farrell has similarly raised the plight of Australian winemakers and sought to promote this industry during his recent visit to South Korea. Still, the aggregate numbers of impacted Australian exports seem to tell a positive story of successful export redirection to alternative markets.

Australia’s exports of copper ores and concentrates to South Korea provide an instructive example in that regard. The value of these exports to South Korea in the six months to August 2022 is 276% higher than it was in the same period in 2020 before China starting blocking imports of Australian copper ores and concentrates. These exports to South Korea have now risen to roughly 66% of the value of these exports to China shortly before that value was reduced to zero with the introduction of trade restrictions. Although global copper prices remain high, this alone presumably doesn’t account for the dramatic rise in the value of these exports to South Korea. So, as with the steep increase in Australia’s barley exports to Saudi Arabia that I noted the last time I looked at the trade numbers, the striking uptick in the value of Australia’s exports of copper ores and concentrates to South Korea is another indicator of the redirection of Australian exports in the wake of China’s trade restrictions.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

Thank you for so comprehensively stating Australia' case. A few niggles:

1. "China’s legally untenable maritime claims in the South China Sea"? The PRC's official, written claims to the SCS are 100% tenable thanks to China's total military control of the Western Pacific. If you intended to limit yourself to 'legally tenable,' explain what laws China contravenes.

2. "tensions over Taiwan and the treatment of Muslims in Xinjiang as barriers to an improved relationship”. There cannot be tensions over Taiwan, which Taiwan, China, Australia, and the UN General Assembly agree is an indissoluble part of China. The fact that America backed the losing side in China's Civil War has no bearing on the matter. We make such statements merely to prove our subjugation to US interests. Ditto Xinjiang. It is part of China and its people are well treated, in any case. There is zero evidence of human rights offenses there, as two Commissions of Inquiry by the World Muslim Council attest.

3. "China’s human rights abuses against ethnic and religious minorities and Australia’s public criticisms of the Chinese government’s policies (e.g., this)”. Your link leads to a statement of Australia's 'concerns' by FM Penny Wong. Given our history of atrocities in Asia, including East Timor most recently, nothing coming from our foreign affairs department can be regarded as authoritive, or even remotely true.