Leader-level diplomacy and AUKUS anniversary analysis

Fortnight of 28 August to 10 September 2023

BCB will shortly be on hiatus for the Australian spring school holidays and will return to your inboxes sometime in early October. In the meantime, this edition includes a short status update on the latest Australia-China leader-level diplomacy, as well as some 2nd anniversary analysis of what the AUKUS pillar 1 submarines mean for China and the bilateral relationship.

Beijing beckons

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in a statement on 7 September:

“I look forward to visiting China later this year to mark the 50th anniversary of Prime Minister Whitlam’s historic visit.”

Quick take:

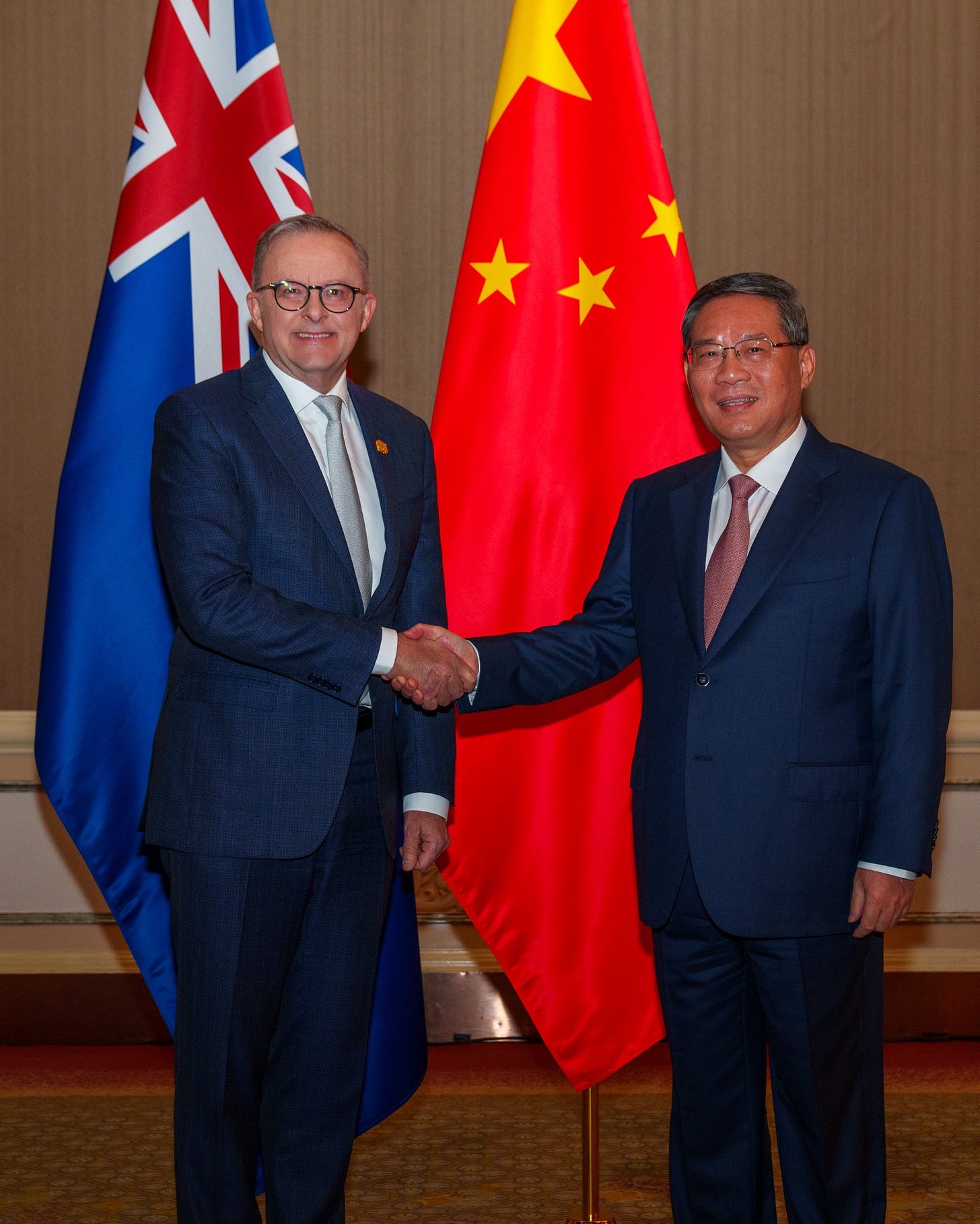

As previously predicted in BCB (e.g., here and here), Prime Minister Albanese will head to China to fete the 50th anniversary of the first-ever visit to the People’s Republic of China by a serving Australian prime minister. Confirmation of the trip came after Prime Minister Albanese met Premier Li Qiang in the margins of the East Asia Summit on 7 September in Jakarta. The opening statements from both the Prime Minister and Premier were upbeat and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs followed with optimistic rhetoric (e.g., here and here) about Prime Minister Albanese’s forthcoming visit to China and the 7th China-Australia High-Level Dialogue, which occurred in Beijing on 7 September more than 3.5 years after its last iteration in Sydney. Prime Minister Albanese also spoke enthusiastically about his meeting with Premier Li and his China trip.

Despite all the positivity, the Chinese government’s readout of the meeting also sounded a cautious note. Although unsurprisingly absent in the Australian government’s coverage of the Albanese-Li meeting, Beijing’s Chinese-language summary included a familiar “hope” that the Australian government will take an “objective and fair” approach to Chinese businesses and investments. Among other issues, this is probably a reference to Beijing’s worries about the conspicuously delayed review of Chinese company Landbridge Group’s 99-year lease of Darwin Port and two recent rejections of Chinese and China-linked investments in Australia’s critical minerals industry.

This Chinese government concern notwithstanding, the Prime Minister’s meeting with the Premier sets the scene for a visit to China in the coming months. It’s likely to be both replete with pomp and circumstance and include a busy trade and business agenda. With Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk apparently heading to Shanghai around the same time for the China International Import Expo and parts of the Australian business community hoping to join the Prime Minister on his visit, there’s a good chance Albanese will go with state/territory and private sector leaders in tow.

AUKUS submarines track towards China

Australian Senator James Paterson, Shadow Minister for Home Affairs and Cyber Security, speaking to Sky News on 4 September:

“What AUKUS recognises is that Australia has a very clear national interest in maintaining the peaceful status quo in the Indo-Pacific region, but particularly in the South China Sea, the East China Sea and the Taiwan Straits.”

Quick take:

Despite the voluminous Australian government messaging about the nuclear-powered submarine component of AUKUS (pillar 1), little has been offered by way of geographic specificity. Albanese government ministers have talked about how AUKUS submarines will “enable us to hold any adversary at risk further from our shores” and “change the calculus for any potential aggressor” without saying where these military effects will be delivered. To the extent that the geographic focus of AUKUS submarines is discussed, it’s usually done at the broad (and amorphous) level of the “region” or the “Indo-Pacific”. (In an interview on the ABC’s ‘Insiders’ on 19 March, Minister for Defence Richard Marles mentioned the South China Sea several times, albeit without explicitly saying that AUKUS submarines would operate there.) Senator Paterson’s comment is a conspicuously rare (and maybe even solitary?) example of a senior political figure nominating in more precise and direct terms some of the locations where the effort of Australia’s nuclear-powered submarines is likely to be focussed.

I tend to think that the Albanese government hasn’t done enough to explain to the Australian people the rationale for and likely uses of AUKUS submarines. So, it won’t surprise readers that I’m supportive of Senator Paterson’s extra transparency about some of the places where AUKUS boats are likely to be headed. But regardless of whether one accepts my argument for more public transparency about the likely uses of Australian nuclear-powered submarines, Senator Paterson’s comment provides useful context for understanding a key part of the reason why China has objected so vociferously to AUKUS since its announcement. Despite their broader Indo-Pacific applications, AUKUS submarines are likely to deliver their most consequential military effects when used on China’s littoral, including in the South and East China seas and the Taiwan Strait and surrounds. In other words, they’re likely to emerge as a central component of Australia’s contribution to efforts to maintain the peaceful status quo in places where China’s overarching and long-term national objectives are to, among other things, redraw the map.

To be clear, this isn’t to suggest that China’s consistently negative reaction is a reason to not acquire AUKUS submarines. The point is simply that the intensity of China’s sustained hostility (e.g., here, here, and here) to AUKUS makes much more sense if Senator Paterson is right in saying that that these platforms are particularly aimed at shaping China’s calculus and thereby maintaining the peaceful status quo in the South and East China seas and the Taiwan Strait and surrounds. Albanese government ministers might be at pains to not talk about the likely geographic focus of AUKUS for obvious diplomatic reasons. When you’re seeking to stabilise ties with China, why would you want to flag the possibility of delivering a deterrent effect in waters around Taiwan? But regardless of the oblique AUKUS rhetoric from Canberra, Beijing seems to have gotten the significance of the sotto voce message loud and clear. China is probably already anticipating a persistent presence of potent Australian submarines in waters off its eastern seaboard in the years and decades ahead.

Addendum: Some readers might query making inferences about the geographic focus of AUKUS submarines based on Senator Paterson’s comment. Not only is he now in opposition, but he was not a member of the second Morrison cabinet that reportedly decided to pursue the AUKUS partnership. Yet as a prominent and influential Coalition national security figure who was Chair of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS) in the lead up to and after the AUKUS submarine announcement, it seems reasonable to infer that he can speak with authority on the rationale for and likely uses of nuclear-powered submarines. Although the PJCIS doesn’t deal with (so far as I’m aware) defence platform procurement or strategy, it has oversight over intelligence collection and assessment agencies that are part of the Australian Defence Organisation and/or have military remits. So, although Senator Paterson might not have been in the room when the initial AUKUS plan was hatched, I’d be inclined to attach weight to his words.

Targeting Chinese forces and infrastructure

From Australia’s 2020 Defence Strategic Update (DSU) released on 1 July 2020:

“The nature of current and future threats … requires Defence to develop a different set of capabilities. These must be able to hold potential adversaries’ forces and infrastructure at risk from a greater distance, and therefore influence their calculus of costs involved in threatening Australian interests.”

Quick take:

The DSU was released more than a year before AUKUS was publicly announced in September 2021. It was also published well before the Australian proposal to acquire nuclear-powered submarines was reportedly formally broached with two key members of the Biden White House’s National Security Council in May 2021. Despite preceding AUKUS, Albanese government ministers still use parts of the DSU’s phraseology verbatim when seeking to explain the rationale for nuclear-powered submarines. At the National Press Club on 17 April, Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong doffed her cap to the DSU when stepping through the case for AUKUS: “taking responsibility for our security means being able to hold potential adversaries’ forces and infrastructure at risk from a greater distance. By having strong defence capabilities of our own, and by working with partners investing in their own capabilities, we change the calculus for any potential aggressor.”

The use of DSU language to explain AUKUS submarines is intriguing considering that this document was written and released well before Washington and London had confirmed that the plan for Australian nuclear-powered submarines was viable. This raises some tantalising questions. For example, is the Albanese government using the DSU language to explain the case for the AUKUS boats because that 2020 document had been pre-emptively drafted to take account of the nuclear-powered submarine capability leap that had been tentatively explored as early as March/April 2020?

Leaving this and related queries to one side, the DSU explanation for AUKUS submarines pairs dramatically with the possibility that they will generate their most consequential military effects in the South and East China seas and the Taiwan Strait and surrounds. Given the attributes of AUKUS boats, their DSU-inspired rationale, and Australia’s interests in maintaining a peaceful regional status quo, Beijing might reasonably conclude that these submarines will be used to threaten Chinese forces and infrastructure should China seek to change the status quo in the South and East China seas and the Taiwan Strait with force. So, as well as potentially tracking and threatening China’s seaborne 2nd strike nuclear capability in the form of its ballistic missile-armed submarines (SSBNs) based on Hainan Island, Beijing might judge that, in extremis, AUKUS boats will be used to endanger its military bases in the South China Sea and possibly also those on the Chinese mainland.

Of course, these potential military uses of nuclear-powered submarines against China are hardly the full AUKUS story. Naval platforms are by their nature versatile and multi-role. A submarine can be used, depending on the political and operational requirements, to deliver a military deterrent effect, perform a public diplomacy function via a port visit, or deepen a bilateral security relationship via participation in a joint exercise. Although nuclear-powered submarines could thereby be used to bring vastly different elements of Australian statecraft to life, their greatest strengths are arguably their intelligence gathering and high-end warfighting capabilities. With “speed, stealth, and endurance” to outmatch any conventionally powered submarine and presumably armed with Tomahawk cruise missiles capable of attacking targets on land, these Australian boats will be among the most potent undersea military platforms plying the Indo-Pacific. And to the extent that they’re operating in the South and East China seas and the waters around Taiwan, they’ll be the among the greatest threats to China’s second-strike SSBNs and, in a conflict scenario, the safety of Chinese forces and infrastructure in China’s southern, eastern, and possibly also northern theatre commands.

To be clear, this is not to take a position on whether Australia should be in the business of seeking to change China’s calculus by signalling to Beijing its ability to track and endanger its SSBNs and/or threaten Chinese forces and infrastructure on its eastern seaboard. The risk and reward calculations required to make a judgement on that weighty issue are far too complex to unpack here. Moreover, my presentation of how China might plausibly perceive Australia’s AUKUS submarines is far from definitive. Other interpretations are possible, and any open-source account is likely to be at least somewhat speculative owing to the paucity of authoritative and detailed Australian government explanations of the likely uses of AUKUS submarines. Finally, with Australia still years away from operating nuclear-powered submarines and the delivery of the full complement of boats expected to take until the 2050s, the geographic focus and military role of the AUKUS platform could evolve dramatically depending on the shape of world politics in the coming years and decades.

Those caveats notwithstanding, if the above assessments about AUKUS submarines are broadly accurate (admittedly, a bigger “if” than usual from me), then we shouldn’t expect the Chinese government’s diplomatic and disinformation campaign against Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines to subside any time soon. We should equally be prepared for the likelihood that AUKUS will significantly heighten China’s threat perception of Australia over time and be an enduring and possibly growing source of frustration in Beijing. By virtue of their speed, stealth, and especially endurance, AUKUS submarines have the potential to directly pit significant Australian military power against China’s efforts to overturn aspects of the maritime and territorial status quo in the South and East China seas and the Taiwan Strait and surrounds. More so than any previous Australian military acquisition, nuclear-powered submarines will allow Australia to contribute substantially to efforts to thwart China’s revanchist maritime and territorial ambitions on its eastern periphery. Viewed from the perspectives of regional security and Australian statecraft, that might be a good thing. But given the centrality of the South and East China seas and especially Taiwan in China’s long-term national goals, AUKUS submarines are for Beijing another would-be roadblock on the path towards the “rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

Even if we were responsible for “maintaining the peaceful status quo in the South and East China seas and the Taiwan Strait,” which we are not, we cannot do so.

We are far more heavily outgunned in the SCS than is Ukraine against Russia.

Not only have we no answer to an opening salvo of 30,000 IRBMs that knock out our bases, but our only choices would then be to back down or launch a 100% suicidal nuclear attack on the Mainland.

PS our ships are fewer, older, and weakly armed, our missiles are a generation behind China’s, and since we deindustrialized, we can’t fight a war against the world’s leading industrial nation.