Unwinding China's wine duties, Australia's leverage, and BCB bilateral predictions

Fortnight of 24 July to 6 August 2023

Hi all,

A couple of quick announcements:

Due to some forthcoming intensive teaching commitments, the next BCB will cover the three-week period of 7 to 27 August and won’t reach your inboxes until the week of 28 August.

From this edition onwards, I’ll start trialling a new section of predictions about bilateral ties. Since its inception, BCB has sought to offer ad hoc forecasts about the future trajectory of the Australia-China relationship. This new section is designed to provide a standing and regularly updated set of predictions regarding key bilateral milestones and future developments. Needless to say, these bilateral predictions will be based on reading way too many official statements and press conference transcripts rather than any privileged information. But hopefully they’ll still help reduce uncertainty and offer a broadly accurate guide to the future of the Australia-China relationship. I’ll refine the format and style of this predictions section in coming editions.

As always, please don’t hesitate to reach out if you have any feedback, especially if it’s critical and/or constructive. I’d also be keen to hear about any areas of policy and politics that you’d like me to cover in the new BCB bilateral predictions section.

Cheers,

Ben

Unwinding China’s wine duties

Minister for Trade and Tourism Don Farrell speaking on 4 August, a day before the removal of China’s duties on Australian barley:

“We intend to use this process as a template for resolving the issue in respect of wine, which is still ongoing. We do have a WTO [World Trade Organization] case in respect of wine and, of course, we’d like to see this process used to resolve that issue as we seek to resolve all of those outstanding issues.”

Quick take:

As previously predicted, China’s duties on Australian barley came tumbling down before Canberra resumed legal proceedings in the WTO. With the Albanese government having flagged back in April its intention to pursue a similar “pathway” in relation to China’s duties on Australian wine, the focus has quickly shifted to that ongoing WTO dispute. Considering that the pathway on barley duties reportedly opened up thanks to a WTO draft ruling that found in favour of Australia and was shared with both Canberra and Beijing, it’s still unclear when a similar pathway on wine duties might emerge. Notwithstanding the lack of public indication of any draft WTO ruling vis-à-vis wine duties, the scene looks set for a similarly staged removal of those trade barriers in the coming months. At the very least, Canberra is likely to face minimal domestic resistance to such a plan considering the Opposition has backed in the Albanese government’s compromise solution of suspending legal proceedings in exchange for the expedited review and eventual removal of duties, followed by the discontinuation of the WTO case.

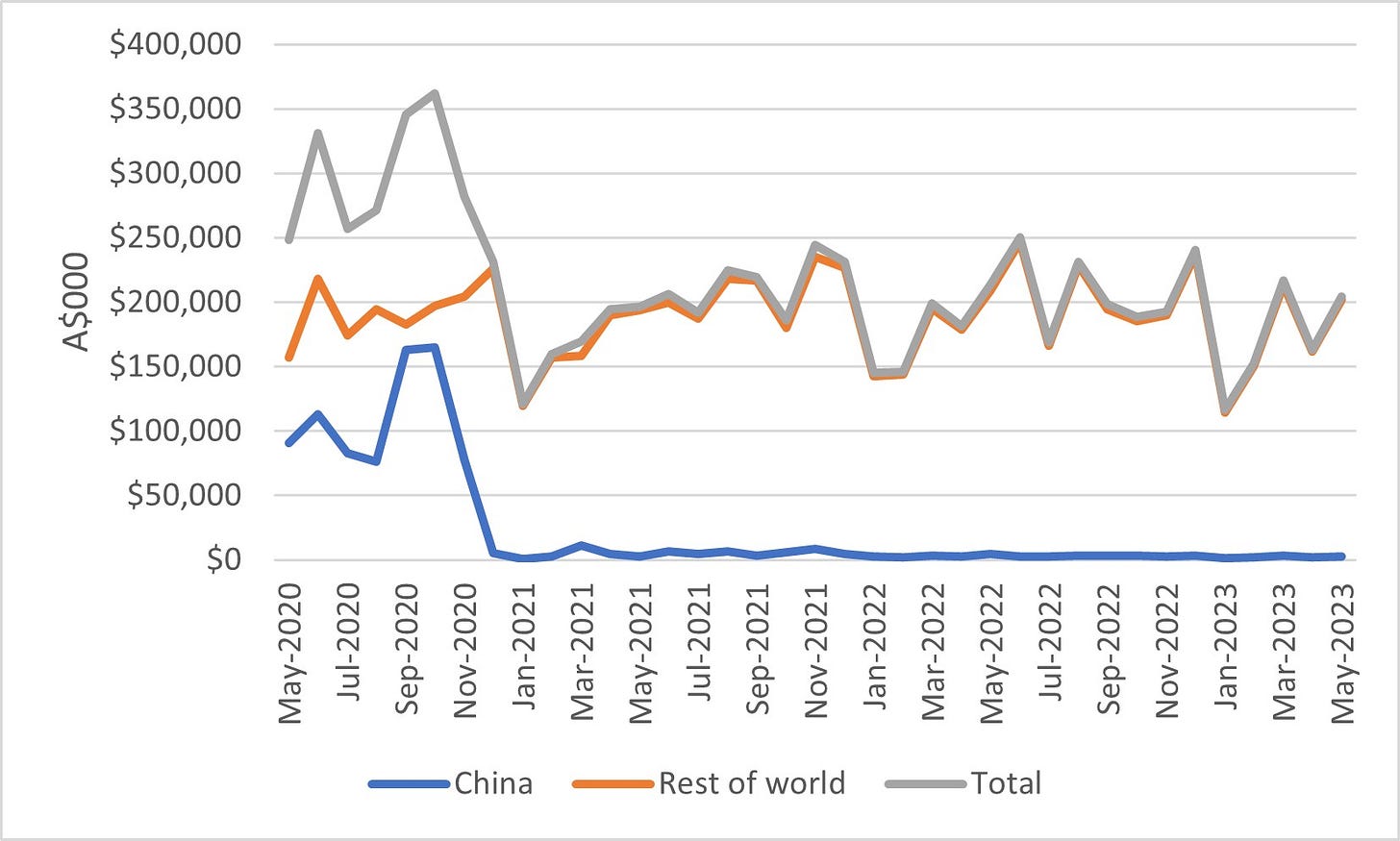

Australian wine exporters have been able to redirect to alternative markets to some extent in the face of Chinese duties that were as high as 218% (though not in all cases). And yet wine has been much harder hit than most other exports targeted by China’s trade restrictions. Although it’s admittedly an imprecise measure that doesn’t account for various climactic and market factors, it’s still striking that the average monthly value of Australia’s alcoholic beverage exports (mostly wine) in the six months to May 2023 is just 60% of the average monthly value prior to the announcement of China’s duties in November 2020 (see graph below). Along with Australian lobster fishers, winemakers have probably had the toughest time in the wake of China’s trade restrictions owing, among other factors, to the lack of comparable alternative consumer markets, the non-fungible nature of wine vintages and varieties, and the extent to which parts of the Australian wine industry were geared towards the lucrative Chinese market specifically. These difficulties persist even as some Australian wine producers pursue workarounds such as launching Chinese-made verities. All this gives the Albanese government extra impetus to push hard for a barley-style pathway for the removal of wine duties. Or, as Minister for Trade and Tourism Farrell put it on 4 August: “I’m hoping the [barley duties] template … will work to ensure that fantastic Australian wine gets back on the tables of Chinese consumers.” Will Minister Farrell get what he wants? In short, probably. But for more, see the final bilateral predictions section of this edition.

Appraising Australia’s China leverage

China’s Ambassador to New Zealand, Wang Xiaolong, as quoted by Reuters on 1 August:

“The CPTPP [Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership] is important for us. Not because it’ll be easy but exactly because it will be difficult and tough.”

Quick take:

This is just the latest in a long series of datapoints suggesting that China is determined to keep prosecuting its case for CPTPP membership. There are multiple plausible interpretations of Beijing’s motives and China’s bid creates complex geostrategic calculations for Australia. But aside from those pointy analytical and policy questions, China’s CPTPP campaign also gestures at the possibility of growing Australian leverage in the bilateral relationship. On the CPTPP and what looks like a lengthening list of policy questions, Beijing is hoping to induce Canberra to take or withhold particular actions. Beyond backing China’s bid for entry into the CPTPP, Beijing also appears to be asking Canberra to:

confirm a leader-level visit to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the first trip to the People’s Republic of China by a serving Australian prime minister;

hold off from further restricting access to the Australian market for consumer-facing Chinese technology companies;

finalise the long-awaited Albanese government response to the review of Landbridge Group’s 99-year Darwin Port lease (and presumably in such a way as to minimise changes to the Chinese company’s current operations);

hand over an Australian citizen and a resident following Hong Kong authorities issuing arrest warrants and bounties;

resume the Australia-China Human Rights Dialogue, which last occurred in 2014; and

approve more military engagements between the Australian Defence Force and the People’s Liberation Army. (These last two requests are admittedly less certain given that although it’s plausible to infer them from Chinese Ambassador Xiao Qian’s past comments, it’s not obvious that the Chinese government has formally and clearly made these requests.)

This is presumably not the full list and I’ll expand it as more examples come to light. I hasten to add that highlighting Beijing’s asks isn’t to suggest either that Canberra should rebuff all of these requests or give the Chinese government all of what it wants. Indeed, in the case of the Australian citizen and resident being pursued by Hong Kong authorities, the only morally justifiable answer seems pretty clear: Australia should flatly refuse the request and instead look at avenues to hold to account the decisionmakers responsible for the arrest warrants and bounties. But beyond that case, the other requests listed above are (to varying degrees) harder to adjudicate and involve complex political and policy calculations with a wide range of, often-competing, domestic and international equities. I won’t try in the limited space I have here to assess the wisdom of Canberra going one way or the other on these other requests. The point is rather that right now Australia holds quite a few cards in the bilateral relationship that Beijing is hoping to get Canberra to play in particular ways. And crucially, unlike much-debated past Chinese government complaints, these are cases in which China is seeking to persuade Australia to take/not take specific new actions rather than punishing Canberra for perceived past misdeeds. To put it crudely, this may mean that China has an extra incentive to go soft on Australia (at least at this moment).

Although the case is far from clearcut, these Chinese government requests would seem to give Australia some extra leverage over China to further press priorities like the removal of trade restrictions and progress on consular cases. Similarly, these requests might mean that Beijing won’t react as harshly to possible Australian decisions to sanction human rights abusers or visibly step up engagement with Taiwan. In other words, with Beijing hoping that Canberra will assent to its requests to advance some areas of the bilateral relationship and hold off from certain actions, the Albanese government might have both additional leverage to prosecute its interests and extra license to take decisions that the Chinese government might not like. For your consideration, Canberra.

BCB bilateral predictions

A pathway for the removal of China’s duties on wine in 2023

Probability

Likely * (circa 70% chance)

Background

When the pathway for the removal of barley duties was announced in April, Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong said: “the Australian Government would expect a similar process to be followed in relation to the trade barriers which exist on Australian wine.” Since then, we’ve seen a series of positive indicators (though, admittedly, inconclusive) for Australian wine exporters, including: the Perth Consul General Long Dingbin visiting Margaret River wineries in June, Minister for Trade and Tourism Farrell’s warmly received gift of a bottle of South Australian red to his Chinese counterpart while in Beijing in May, and Vice Minister Ma Youxiang’s seemingly happy jaunt to Canberra’s wine district in April. More broadly, announcing a pathway for the removal of wine duties is one of the next major milestones in the stabilisation and repair of the Australia-China relationship, which is a process that Beijing seems keen to see continue.

Recent developments

The successful pathway to remove barley duties potentially paves the way for a similar resolution of the WTO dispute over wine duties.

A visit to Australia by China’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi and/or Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao in 2023 (most likely prior to a prime ministerial trip to Beijing)

Probability

Almost certain (circa 95% chance)

Background

Minister for Trade and Tourism Farrell previously invited his Chinese counterpart to Australia and received a positive response. Meanwhile, the previous Minister of Foreign Affairs Qin Gang was expected to visit Australia in July before he was summarily removed from his post. A Chinese ministerial visit to Australia in the trade and/or foreign affairs portfolios would be a logical next step in the process of stabilising and repairing bilateral ties and would prepare the ground for a leader-level visit to China later this year.

Recent developments

The removal of China’s barley duties and the growing probability of a leader-level trip to Beijing increase the chances of a ministerial visit to Australia in the foreign affairs and/or trade portfolios in the next few months.

A prime ministerial visit to China in 2023 (October/November still most likely)

Probability

Highly likely (circa 90% chance)

Background

Beijing has issued an invitation and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has said that he’d “like to take up the opportunity to visit China” and expects to do so “this year”. Although both sides want the visit to occur, Canberra appears unwilling to confirm that it will take place given longstanding and acute Australian concerns about, among other issues, the prolonged detention of Australians in China and ongoing trade restrictions on wine, beef, and lobster. Nevertheless, Prime Minister Albanese’s domestic political motivations, Canberra’s reluctance to rule out a visit if its trade and consular expectations aren’t met, and Beijing’s apparent keenness to fete the 50th anniversary of Gough Whitlam’s prime ministerial trip, among other factors, all count in favour of a leader-level visit to China.

Recent developments

China’s removal of barley duties and confident comments about the visit from the Prime Minister and his ministers (e.g., here, here, and here) make a visit later this year increasingly likely.

* For those curious about the terminology and approximate numerical probabilities, I’m (roughly) following the UK’s Professional Head of Intelligence Assessment Probability Yardstick. For more details, see here.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

Love this prediction section you have introduced!

Australia was just given a multibillion dollar lesson in what happens to backstabbing 'partners'. It was a mild rebuke, richly earned.

Since then, our behavior towards China has become much worse, more aggressive and dismissive.

Expect things to get much worse.