More diplomatic momentum, an alternative to China sanctions, and trade with Taiwan

Fortnight of 19 February to 3 March 2024

This is the free fortnightly BCB newsletter. For readers looking for breaking analysis of major bilateral developments, BCB now also offers a paid subscription add-on. BCB in Brief provides quick assessments of the latest stories shaping the Australia-China relationship. You can upgrade to a paid subscription here:

Deepening diplomatic engagement and loosening trade restrictions

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese speaking on 20 February:

“I look forward to welcoming Premier Li [Qiang] here, this year, on the return visit.”

Quick take:

As I’ve suggested previously, the first Chinese leader-level visit to Australia in at least seven years could take place in November to coincide with some big ten-year bilateral anniversaries, or perhaps even as early as mid-year. And assuming this visit occurs, it’ll almost certainly come on the back of a trip to Australia by China’s Minister of Foreign Affairs. Despite the coy comment from the Chinese government about the mooted foreign ministerial visit, it looks likely to take place as early as mid- to late-March following China’s Two Sessions. This would be the first visit to Australia by a Chinese foreign minister in circa seven years and is expected to see Australia host the bilateral Foreign and Strategic Dialogue for the first time in just as long.

Who precisely will come as the Chinese foreign minister remains to be seen. Reporting in January gave the impression that it might be a newly promoted Liu Jianchao, who’s currently head of the Chinese Communist Party’s International Department. But the latest indicators suggest that Wang Yi might still be foreign minister even after the Two Sessions. The pomp of Wang’s 7 March press conference seems to increase the likelihood of that scenario. Another possibility is Ma Zhaoxu, who’s currently Executive Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs and was previously Ambassador to Australia. Interestingly, all three are well known to Australia: Wang has met every Australian foreign minister since at least Bob Carr and Liu and Ma were both in Canberra just last year.

Notwithstanding the uncertainty about who exactly Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong hosts and the longer timeline for Premier Li’s trip, both of these visits look all but certain to go ahead. Enduring and emerging points of tension will continue bubbling up in the bilateral relationship. In just the last fortnight alone, an Australian was jailed for attempted foreign interference on China’s behalf, the Ministry of State Security was identified (albeit not directly and publicly by the Australian government) as having an “A-team” with Australia as “its priority target,” and Canberra continued to express deep concerns about the grim fate of Australian writer Yang Hengjun (here, here, and here). But despite these and the long list of other disputes, both Canberra and Beijing appear intent on keeping bilateral relationship repair humming along.

Per Minister for Trade and Tourism Don Farrell’s 26 February discussion with Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao, China looks poised to remove its duties on Australian wine and then potentially tackle the remaining trade restrictions on lobster and beef. Recent Chinese press reporting (here and here) and the Ministry of Commerce’s readout of the Farrell-Wang meeting don’t provide grounds for doubting the widely expected March announcement of the removal of the wine duties. Meanwhile, Australia continues to take a restrained approach to some especially sensitive issues for China. Among other past and ongoing examples of policy caution, Canberra has expressed “grave concern” while stopping short of sanctioning Chinese officials implicated in severe and systematic human rights abuses. And in recent weeks, Australia didn’t join allies and partners who have sanctioned Chinese companies for aiding Russia’s war effort in Ukraine. So, despite regular bilateral flareups, the path still looks clear for an imminent Chinese foreign ministerial visit and a leader-level trip later this year.

Options short of sanctioning Chinese officials

Shadow Minister for Immigration and Citizenship Dan Tehan speaking in Parliament on 27 February about the Autonomous Sanctions Amendment Bill 2024:

“[T]he coalition … reiterates its offer of bipartisanship for the government to impose targeted sanctions in line with those of our allies, whether in response to Russian abuses, human rights abuses in Xinjiang or numerous other instances of human rights violations.”

Quick take:

The opposition has again pledged its support for Australian sanctions against Chinese officials and entities implicated in severe and systematic human rights abuses in Xinjiang (past examples of such offers include this, this, and this). Despite this and Minister for Foreign Affairs Wong’s caveated support for such sanctions when she was in opposition (here and here), Australia is unlikely to impose them this year. Notwithstanding the prolific use of such tools against less politically contentious targets, such as Russia, Iran, and Myanmar, the Albanese government has to date been unwilling to sanction Chinese officials. And with Prime Minister Albanese and his colleagues likely putting a premium on keeping the bilateral relationship on an even keel in the lead up to the next federal election, potentially destabilising sanctions against China seem particularly unlikely.

I won’t try to again unpick the rights and wrongs of Canberra’s unwillingness to pull the trigger on such sanctions (I’ve previously tried to do that here and here). Regardless, there’s presumably more that can be done to at least scrutinise whether those implicated in human rights abuses are able to, as Tehan described it, access “our economy and the freedoms that our democracy allows.” The opposition and members of the crossbench could start by publicly and repeatedly asking whether the Chinese officials who are plausible candidates for potential Australian financial and travel sanctions have assets in Australia or have visited in recent years. For example, does Wang Junzheng, who held a senior Party position in Xinjiang and now holds one in Tibet, have financial interests in Australia or has he visited in recent years? Similar questions could be asked about a range of other officials who have presided over human rights abuses. The opposition and crossbench might also reasonably ask whether the immediate family members of Wang and others have enjoyed financial and travel opportunities in Australia.

What these kinds of questions would yield remains to be seen. Such financial and travel ties with Australia might seem prima facie unlikely in the case of officials overseeing repressive and internationally controversial policies in Xinjiang, Tibet, and elsewhere. But considering that many senior Chinese officials likely still have overseas assets and probably aren’t averse to international travel, such connections are still possible. And even if senior officials responsible for repressive policies in Xinjiang, Tibet, and other western regions don’t have those kinds of connections with Australia, it seems highly likely that at least some Hong Kong officials who’ve overseen the deteriorating human rights situation there would. Given the long-standing and deep people-to-people ties between Australia and Hong Kong, presumably at least some past and present senior figures in the Hong Kong security apparatus, which includes Tang Ping-keung, John KC Lee, and many others, would have assets in Australia or have at least visited in recent years. And on a matter of particular interest to Australians, it seems possible that some of the less senior Hong Kong officials directly responsible for bounties on an Australian citizen and resident might also have assets in Australia or have travelled here.

None of this is to take a position on whether the Albanese government should impose sanctions on individuals and entities implicated in human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, and elsewhere in China. Indeed, some such sanctions might not even be currently possible or effective because of retirements and personnel changes. But even if sanctions aren’t imposed, there’s still a case for more clarity on whether Australia is unwittingly providing financial and travel opportunities to individuals who’ve overseen policies, which in the case of Xinjiang, “may constitute … crimes against humanity.” Given the many massive Australian national interest equities in a stable Australia-China relationship, the Albanese government might ultimately have good reasons for not sanctioning Chinese officials. But in lieu of imposing such high-stakes sanctions, there’s at least a case for the opposition and parliamentary crossbench to publicly ask more searching questions about whether Australia is providing financial and travel opportunities to individuals that most Australians would like to see sanctioned.

Australia’s trade with Taiwan

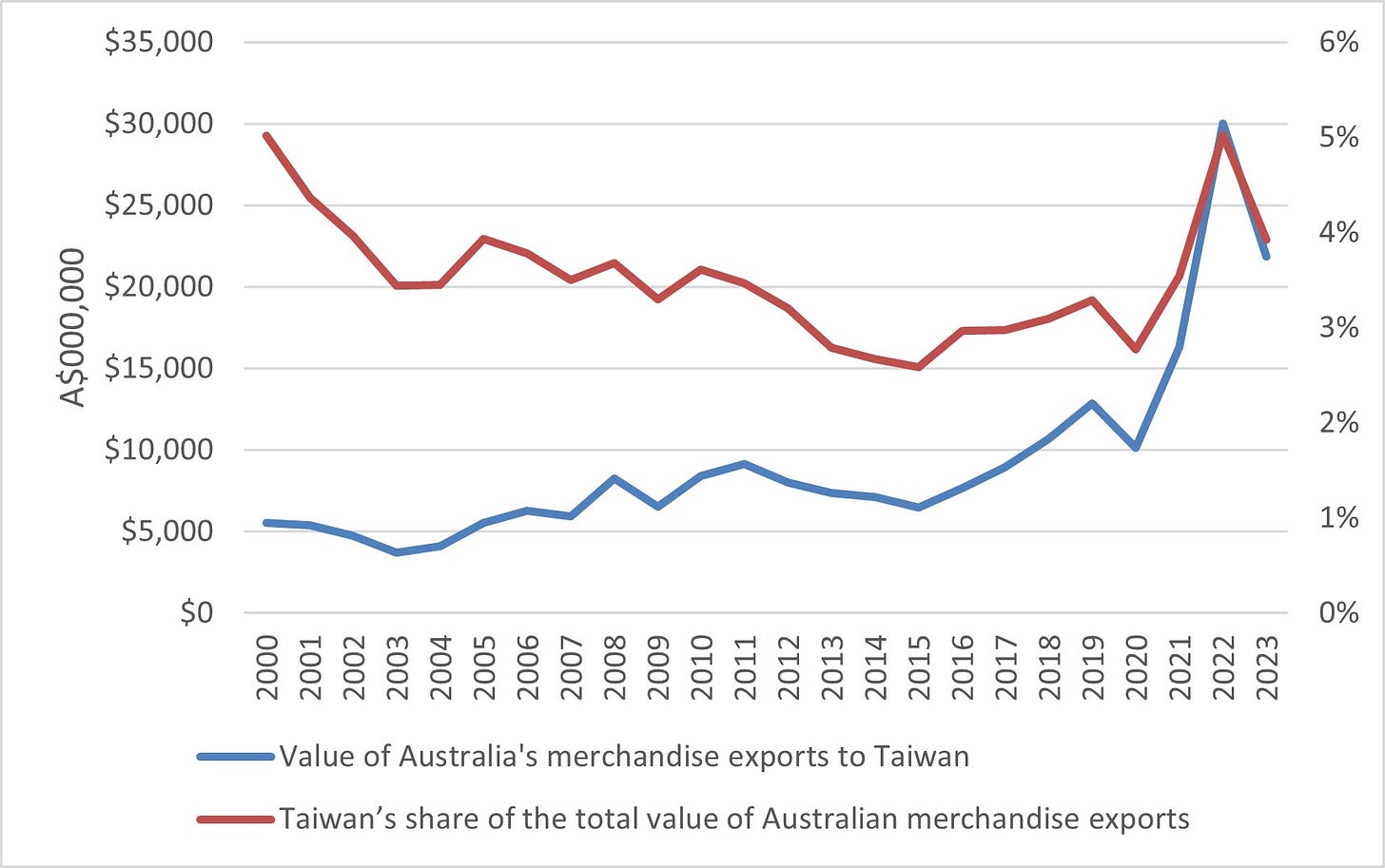

The value of Australia’s merchandise exports to Taiwan and Taiwan’s share of the total value of Australian merchandise exports, 2000-23 (calculations based on data available here and here):

Quick take:

For decades, Taiwan has been the destination for between circa 3% and 5% of the total annual value of Australia’s merchandise exports. This puts Taiwan among Australia’s most significant trading partners. In 2022, it was Australia’s fourth most lucrative merchandise export destination and sixth most valuable export market overall. With the prices of Australia’s two biggest exports (by far) to Taiwan—coal and natural gas—declining dramatically from sharp peaks in 2022, Taiwan dropped a spot to become Australia’s fifth most lucrative merchandise export market in 2023, behind India. Despite the decline in the value and the proportion of Australia’s merchandise exports going to Taiwan in 2023, this data still underscores Taiwan’s outlier position among Australia’s top trading partners. As Mark Harrison and I have argued previously, Taiwan was in 2022 the only one of Australia’s top-ten export markets with which Canberra didn’t have either a bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA) or shared membership of a regional FTA.

Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the case for an Australia-Taiwan FTA is a slam dunk. The bulk of Australia’s merchandise exports to Taiwan by value are resources and energy, which already enjoy low tariff rates. In 2022, coal, natural gas, and iron ore alone accounted for approximately 85% of the total value of Australia’s merchandise exports to Taiwan. Meanwhile, with only a few relatively small economies having FTAs with Taipei, many of Australia’s biggest competitors don’t enjoy trade access in Taiwan that Australia doesn’t already have. Then there’s the China factor. There’s little doubt that Beijing would be unhappy with Canberra pursuing an FTA with Taipei. Having pressured the Turnbull government out of just such a plan, China has form for acting on its opposition to other countries formalising deeper trade ties with Taiwan. China’s discontent might be even more acute now following the historically unprecedented third consecutive presidential term for Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party, which Beijing distrusts deeply. Yes, both Singapore and New Zealand have what amount to FTAs with Taiwan, but these were inked when ties between Beijing and Taipei were warmer and before China redoubled its international efforts to politically, diplomatically, and economically isolate Taiwan.

There are, however, counterpoints to all these reasons for not pursuing an FTA with Taiwan. Although Australia’s resources and energy sectors might not benefit much from such an FTA, at least some Australian agricultural exporters would. They face tariffs north of 15% in the Taiwanese market. With Taiwan one of the wealthiest consumer markets in Asia and some premium Australian agricultural exports among the hardest hit by China’s trade restrictions, there’s an even stronger case for greater trade access to the Taiwanese market for Australia’s primary producers. Not only are Australia’s agricultural exporters at a disadvantage vis-à-vis their New Zealand competitors, who already enjoy an FTA with Taiwan and tariff rates close to zero, but there’d likely be gains for Australia in securing the kind of access to the Taiwanese market that most economies don’t enjoy. Assessing the risk that pursuing an FTA with Taiwan would lead to reprisals from China or at least a slowdown or reversal of relationship repair is complex and involves many unknowns. I’ve tried to grapple with this issue here, here, and here. I’m under no illusion that those are complete or totally compelling assessments of the impact on the Australia-China relationship of Canberra pursuing an FTA with Taipei. Nevertheless, I’d still on balance be inclined to assess that Beijing wouldn’t let Canberra’s pursuit of an FTA with Taipei jeopardise the last couple of years of Australia-China relationship repair.

The above points are no doubt contestable, and that’s certainly true of the last one. Adjudicating the full tally of costs and benefits of Australia pursuing an FTA with Taiwan would require much more analysis. But even without fully unpacking that, the above merchandise exports data at least underscores the oddity that is Australia’s lack of FTA with Taiwan. As well as being the only one of Australia’s top five merchandise export destinations with which it doesn’t have an FTA, Taiwan is considerably more economically important for Australian businesses than some other markets with which Canberra has pursued trade liberalisation in recent years. For example, Australia’s merchandise exports to Taiwan in 2023 were worth approximately four times the value of those to the United Kingdom (UK) and nearly five times the value of those to the United Arab Emirates (UAE). (We don’t yet have the 2023 Australian services trade data to make a comparison of overall export values.) That’s not to say that the Australia-UK FTA or the planned FTA with the UAE aren’t good initiatives. But it does at least suggest a mismatch between Australia’s trade diversification agenda of expanding access in more markets and Canberra’s unwillingness pursue an FTA with Taipei.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

the Albanese government might ultimately have good reasons for not sanctioning Chinese officials??

I suspect they have the ultimate good reason: there’s not a shred of evidence to support such allegations. It’s another WMD/invisible atrocity story.