Stalling trade stabilisation, live lobster languishes, and Chinese EV tariffs

Weeks of 19 August to 15-ish September 2024

Stalling bilateral trade stabilisation

Minister for Trade and Tourism Don Farrell speaking to the ABC on 18 September 2024 about China’s ongoing trade restrictions on Australian live lobster:

“I’m confident that one of these days I’ll be able to come into this studio and say … it’s fixed.”

Quick take:

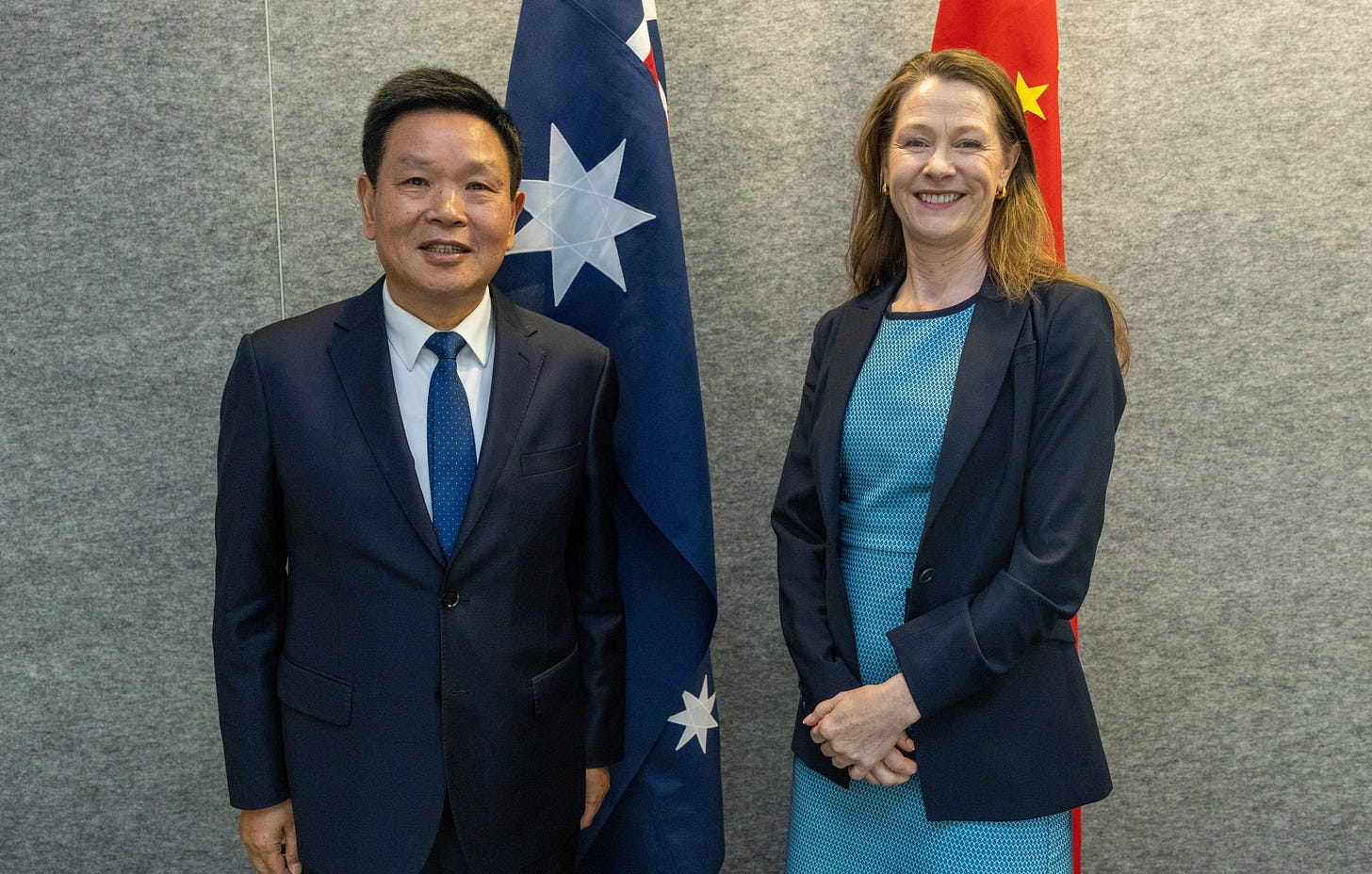

Diplomatic and political ties between Australia and China continued their upward trajectory in recent weeks. As well as a meeting at the ministerial level in the climate change portfolio, there were engagements at the official and junior ministerial levels. The stage is now also set for significant bilateral meetings later this month and in October. Treasurer Jim Chalmers will visit China “most likely on or around the 27th of September” for the first bilateral Strategic Economic Dialogue (SED) in seven years. In addition to being Australia’s inaugural ministerial visit to China this year, it’ll be the first trip there by an Australian treasurer since Scott Morrison went to Beijing for the third and most recent SED in September 2017. Meanwhile, following at least four bipartisan visits to Taiwan by Australian parliamentarians in less than a year (here, here, here, and here), the first parliamentary delegation to China in nearly five years will travel next month.

Despite these engagements and general bilateral positivity from Chinese diplomats in Australia (here, here, and here), there are still no concrete signs of an end to China’s campaign of economic coercion, which has now lasted four years and four months, and counting. Whispers are circulating about the likely removal in the coming weeks of the trade restrictions on two red meat exporters. But the biggest outstanding trade blockage on Australian live lobster looks likely to remain in place for now.

Following Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong’s acknowledgement in August of official-level efforts to resolve the live lobster trade blockages, Australia’s Lobster Working Group (LWG) on 18 September confirmed that an extensive and ongoing process would still need to play out before this export can formally regain access to the Chinese market. This process includes discussions between Australian and Chinese officials in Beijing this week, as well as consultations with Australia’s lobster industry regarding China’s requirements for monitoring, testing, registration, and auditing. Although the LWG “remain[s] cautiously optimistic that a resolution can be achieved in the coming months,” the extensive and ongoing process apparently required to achieve that outcome suggests that China’s trade restrictions on Australian live lobster could last until the end of 2024 and perhaps even longer.

Will Australian live lobster languish long term?

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese responding on 3 September 2024 to a journalist at a press conference in Perth:

“So, we want to see [the removal of China’s trade restrictions on live lobster] happen. But to put it in perspective … I expect that the trade to China from goods that were the subject of impediments will [this year] be greater than $20 billion. And the big winners of that will particularly be here in [Western Australia].”

Quick take:

When delivering speeches that touch on trade with China, Minister for Foreign Affairs Wong (here and here), her assistant minister Tim Watts, and Minister for Trade and Tourism Farrell still mention the live lobster trade restrictions. Yet Prime Minister Albanese has in recent weeks omitted mention of these impediments in speeches that, among other things, trumpet China’s removal of most of its trade restrictions (here and here). Meanwhile, when quizzed by journalists about the remaining trade restrictions on live lobster, Prime Minister Albanese and his senior ministerial colleagues (here and here) are quick to emphasise that despite this ongoing challenge, China has removed the bulk of its impediments on Australian exports.

There’s nothing especially surprising about the Albanese government wanting to emphasise the upside of recent trade progress with China and not dwell on the enduring and painful costs of the remaining trade restrictions on live lobster. Having had previous hopes of relief for live lobster exporters dashed, Prime Minister Albanese and his Cabinet colleagues might be also trying to manage industry and broader public expectations. Still, it’s hard not to be intrigued by what look like Albanese government efforts to recontextualise the remaining trade restrictions on live lobster as one piece of negative news in a mostly positive story about trade blockages with China being removed. This apparent reframing is especially conspicuous because it coincides with a downgrade in the Albanese government’s confidence levels about the removal of the impediments on live lobster. The previously bullish optimism about impending relief in June has been replaced with cautious predictions about the possibility of good news at some point.

Ultimately, it’s hard to know (at least based solely on publicly available information) what’s really motivating China to slow roll the removal of the trade restrictions on live lobster. It’s entirely possible that these blockages are now primarily bureaucratic, and that they’ll be lifted once the official and industry process outlined by the LWG wraps up in the coming months. But if I was forced to take a punt, I’d be inclined to say that the Albanese government’s more circumspect messaging adds credence to the theory that Beijing is seeking to use the remaining trade restrictions on live lobster as leverage. In particular, it seems plausible that Prime Minister Albanese and his ministerial colleagues are now less publicly vocal and more downcast about the removal of the live lobster trade restrictions because China has made quid pro quo requests to which they either can’t, or don’t want to, agree. The official and industry process that the LWG flagged might be real and ongoing. But from the Chinese government’s point of view, this process might largely be aimed at providing plausible deniability for the real political ask that Beijing has made of Canberra. If that’s the case, then the live lobster trade restrictions could last much longer than previously expected. And it’s also possible that their eventual removal, if/when it occurs, will be associated with an Australian decision that China can construe as a concession. That might come in the form of the discontinuation of anti-dumping measures, the approval of a previously stalled Chinese investment, or something else.

Of course, it’s entirely possible that I’m overinterpreting the available evidence and being a tad too conspiratorial. But even if I’ve taken this speculative analysis too far, it still seems likely that the live lobster trade restrictions will remain for a few more months. In the short term, it’s not clear that the General Administration of Customs China (GACC) will agree to Canberra’s proposed approach for addressing Beijing’s requirements regarding monitoring, testing, registration, and auditing. And even following such GACC agreement, it remains to be seen how exactly and by when Australian industry will be able to comply with these requirements. The resumption of direct China Southern Airlines flights from Adelaide to Guangzhou this coning December might lead some to speculate that there’ll soon be another route for live lobsters to quickly get to the Chinese market. But the Albanese government’s more circumspect messaging, the ongoing bureaucratic negotiations, and the possibility of a quid pro quo request from China all suggest that there are still a few twists and turns to come in the path for Australian live lobster to re-enter the Chinese market via official channels.

Will Australia impose tariffs on Chinese EVs?

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Lin Jian responding on 27 August 2024 to a question about Canada’s planned 100% tariff on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs):

“China deplores and opposes this. … China urges Canada to respect facts, observe [World Trade Organization] rules, correct this wrong decision at once, and stop politicising trade issues. China will take all measures necessary to safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese enterprises.”

Quick take:

With Ottawa following Washington with its own tariffs on Chinese EVs and Brussels edging towards similar measures, it appears that a broader move might be on among wealthy democracies. Uncertainty surrounds how these market restrictions on Chinese EVs will evolve longer term. Although the US and Canadian tariff decisions seem unlikely to be reversed, there’s already a push among some European Union (EU) countries to abandon their bloc’s plan. It’s also still unclear what the eventual direction of travel on this issue might be in Japan and the United Kingdom, which are the only G7 jurisdictions not covered in some way by already announced Chinese EV tariff plans. Meanwhile, other wealthy democracies with large automotive industries, such as South Korea, haven’t yet offered firm public indications of what they’ll do.

Still, given the scale and significance of these US, Canadian, and possibly EU EV tariffs, it’s worth considering what Australia might do. Although Washington hasn’t (I don’t think?) said so publicly, it seems likely that the United States would, on balance, welcome Australia imposing tariffs on Chinese EVs. It’s even plausible to imagine that US officials have already made private representations, albeit probably gentle ones, to their Australian counterparts on this issue. As well as adding an extra measure of international backing for US moves, Australian tariffs would likely limit the penetration of Australia’s market by Chinese EVs, which longer term might provide marginal commercial benefits to US car companies. And to the extent that US EV tariffs are part of a broader effort to compete with China economically and technologically, and are thereby more than straightforward domestic industry protectionism, Washington would presumably be especially keen to garner support among its closest allies.

Yet despite the often-tight coordination between Canberra and Washington on many (though, obviously, not all) China policy questions, I strongly doubt that Australia will implement anything like the US tariffs on Chinese EVs. First and foremost, Canberra’s calculation is probably economic. Unlike the US, Canada, and the EU, Australia doesn’t have a large domestic automotive industry to protect and hasn’t for years. This means that there won’t be large-scale domestic industry casualties in Australia if Chinese EVs end up dominating its car market.

Moreover, excluding Chinese EVs from the Australian market with tariffs would likely impose additional costs on businesses and consumers. With Australians already facing steep cost-of-living pressures and inflation uncomfortably high, such tariffs presumably wouldn’t be welcomed domestically. The Albanese government is probably especially turned off by such potentially inflationary measures given that they’re sliding in the polls due to, among other factors, high consumer price rises. To say nothing of the awkwardness of trying to reconcile EV tariffs with Australia’s efforts to reduce carbon emissions and remain broadly true to its liberal economic principles, the looming federal election and inflationary pressures probably provide the Albanese government with all the reasons it needs to not target Chinese automakers.

Then there’s the China factor. Beijing has responded to US, Canadian, and EU tariff announcements with a range of countermeasures, including anti-dumping investigations, World Trade Organization complaints, and an anti-discrimination inquiry. With Australia still pushing for the removal of China’s final trade restrictions on live lobster and red meat, the appetite in Canberra for earning Beijing’s ire again and suffering fresh trade restrictions is likely to be close to zero. As with the Albanese government’s unwillingness to impose sanctions on Chinese officials, entities, and companies implicated in human rights abuses, cyberattacks, and support for Russia’s war against Ukraine, fear of China’s possible trade retribution will probably prompt the Albanese government to avoid EV tariffs. And this caution is likely to be especially acute in the lead up to the next federal election in which the Albanese government will probably campaign on, among other things, the recent stabilisation of the Australia-China relationship.

Regardless of the many and complex rights and wrongs of tariffs on Chinese EVs, there seems to be a vanishingly small chance that Australia will impose similar measures in the coming months. And that’s likely to remain the case even if the typically tougher-on-China Coalition wins the next federal election. Although they’ve repeatedly said that they’d, for example, impose targeted sanctions on Chinese officials and entities implicated in human rights abuses in Xinjiang, they still seem likely to shy away from tariffs on Chinese EVs. The Coalition in recent months has repeatedly emphasised that they’d like to see Australia-China trade ties “grow further” and even double. Given the high likelihood of outrage in Beijing and new trade restrictions if Canberra imposes tariffs of Chinese EVs, it seems that the Coalition would need to eschew such measures if they wanted to achieve their broader objectives for the Australia-China trade relationship. More generally, the Coalition has previously acknowledged and continues recognise the benefits for individuals and businesses of the “lower prices and greater availability of Chinese products” provided by removing tariffs and keeping them off imports.

Australia’s reluctance to impose tariffs on Chinese EVs doesn’t mean there won’t be efforts to scrutinise and more tightly regulate these products. Influential Australian parliamentarians have already raised security concerns about Chinese EVs. And given the volume of data collected by EVs and persistent doubts in many quarters about what Chinese technology companies and their government might do with such information, I’d expect a longer-term push for additional data localisation requirements and Australian consumer protections. But even so, Australia seems unlikely to impose its own tariffs on Chinese EVs.

As always, thank you for reading, and please excuse any errors (typographical or otherwise). Any and all objections, criticisms, and corrections are very much appreciated.

Jesus, what a clueless, imperialistic take on our relationship with our main trading partner!

Not one percent of us understand China's motives because our media refuse to publish and our government refuses to discuss China's complaints with their Ambassador. Here they ae:

1. Foreign investment decisions, with acquisitions blocked on opaque national security grounds in contravention of ChAFTA. Since 2018, more than 10 Chinese investment projects have been rejected by Australia citing ambiguous and unfounded "national security concerns" and restricting areas like infrastructure, agriculture and animal husbandry, while launching more than 100 anti-dumping and anti-subsidy investigations of Chinese products.

2. Banning Huawei Technologies and ZTE from the 5G network, over unfounded national security concerns, doing the bidding of the US by lobbying other countries, foreign interference legislation viewed as targeting China and in the absence of evidence.

3. Politicization and stigmatization of the normal exchanges and cooperation between China and Australia and creating barriers and imposing restrictions, including the revocation of visas for Chinese scholars.

4. Calling for an international independent inquiry into the COV1D-19 virus, as a political manipulation echoing the US attack on China.

5. Spearheading the crusade against China in multilateral forums.

6. Spreading disinformation imported from the US around China's efforts of containing COV1D-19.

7. Legislating scrutiny of agreements with a foreign government targeting China and aiming to torpedo Victoria’s participation in BRI.

8. Providing funding to anti-China think tanks for spreading untrue reports, peddling lies around Xinjiang and so-called China infiltration aimed at manipulating public opinion against China.

9. Early dawn search and reckless seizure of Chinese journalists' homes and properties without charges or explanations

10. Thinly veiled allegations against China of cyber attacks without any evidence

11. Outrageous condemnation of the governing party of China by NGOs

12. Racist attacks against Chinese and Asian people.

13. Unfriendly and antagonistic reports on China by media that poison the atmosphere of bilateral relations. The first non littoral country to make a statement on the South China Sea to the United Nations, siding with the US' anti-China campaign.

14. Incessant wanton interference in China's Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan affair.

China’s deputy ambassador to Australia, Wang Xining: “China is not a cow. I don’t think it would occur to anyone to milk China in its prime while plotting to kill it in the end.”

Paranoia over China, government, media, AFP collusion

By Stuart ReesApr 16, 2021

Chinese dragon feature pic

Credit - Unsplash

The High Court’s current deliberations about the legality of warrants issued last year to the AFP to search the home of John Zhang, part-time assistant to NSW Labor MP Shaoquett Moselmane, are the tip of a massive iceberg of government abuses of power.

John Zhang is a Chinese Australian. Mr Moselmane has Chinese Australian constituents, had been to China to deliver wheelchairs to a Shanghai orphanage and had complimented the Chinese government on its reaction to the Covid outbreak in Wuhan, activities which in police eyes made Shaoquett a person of interest.